The percentage of honor offense reports filed against minority students relative to the undergraduate minority population has been a source of recurring criticism of the honor system.

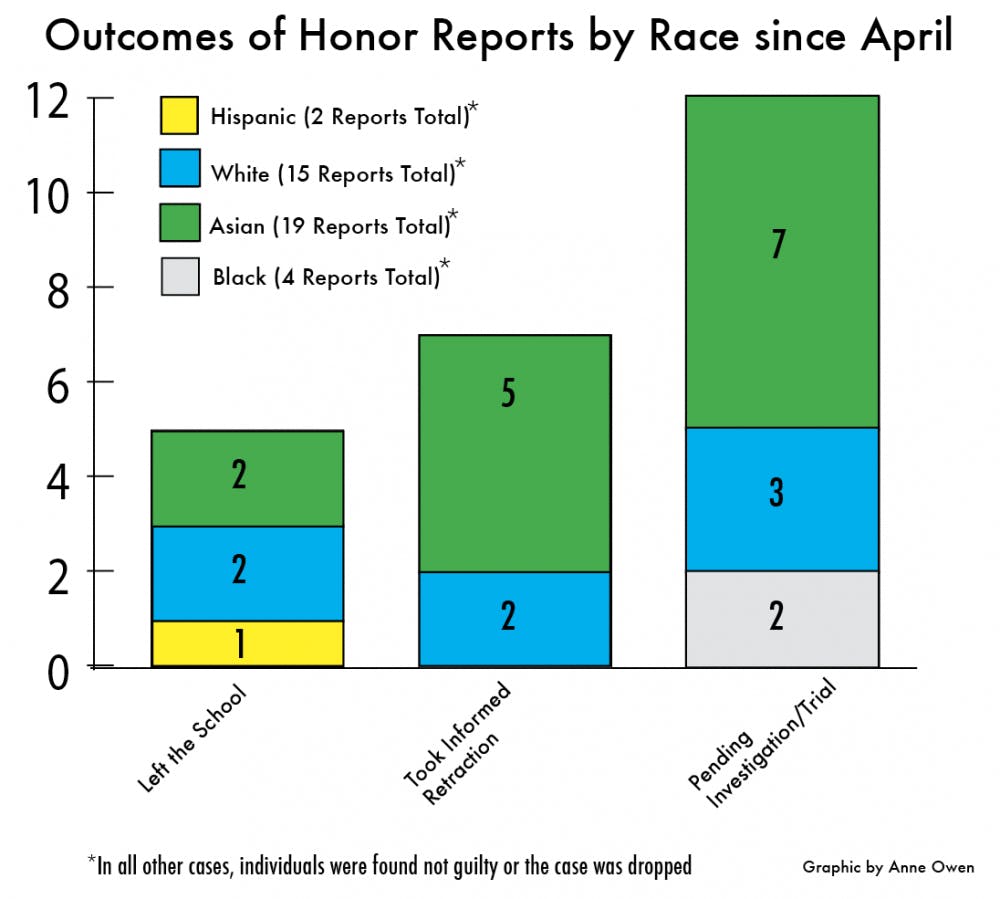

Of the 40 honor offenses filed since April last year, 62.5 percent were filed against minority students — including 15 reports against Asian international students and four against African-American students.

With just 28.3 percent of the undergraduate population identifying as minority students and 6 percent coming in as international students, such rates could suggest a targeting of minority students, either conscious or subconscious.

Regardless of the reasons behind unequal reporting rates, distrust of the honor system among minorities may be happening as a result, said newly-elected College Honor Representative Martese Johnson, a second-year. Johnson considers even the suggestion of minority distrust of honor to be a huge understatement.

“Students I talked to had never voted [in honor elections], ever,” he said, referring to one-on-one conversations with minority students he had during his campaign. “They think honor is out to get them, not something they connect with.”

Honor Committee Chair Evan Behrle, a fourth-year College student, said a lot of concerns about disproportionate reporting are swallowed up once the students enter the Committee.

“We encounter distrust borne out of the disproportionality, which occurs outside our walls,” he said. “We don’t seek out reports. We are proud of how fairly we treat students [once they enter the system], [and] the equitable distribution of verdicts.”

However, Behrle sees the challenge as Honor’s problem.

“Disproportionate reporting is still our responsibility,” he said. “If not ours, who’s is it?”

Speaking to the possible causes of higher reporting against minorities, Behrle pinpointed three distinct problems: a lack of understanding among international students, spotlighting of minority offenses and dimming of offenses committed by white students.

Among international students, “there is a problem of fully internalizing policies that govern the honor system, especially around plagiarism and collaboration,” he said.

“We encounter distrust borne out of the disproportionality,

which occurs outside our walls,” he said.

“We don’t seek out reports. We are proud of how fairly

we treat students [once they enter the system],

[and] the equitable distribution of verdicts.”

The Honor Committee has prepared a brochure in conjunction with the International Studies Office about the honor system for incoming international students and holds a panel discussion during the international student orientation before the first week of classes in August.

The trends of spotlighting some students’ offenses and dimming others’ remains a problem in peer reporting, Behrle said.

“When a student is really contrite and apologizes, there may be a subconscious bias so that the faculty member or student may be more forgiving of the offense,” he said.

That “subconscious bias” toward a student who is part of a majority population can lead to his or her offenses going unreported. In contrast, a student who is identified as “different from the mainstream is more likely to attract attention, subconsciously, and more likely to be reported,” Behrle said.

Though Behrle expressed his frustration that problems of reporting and outreach are often collapsed, he acknowledged disproportionate reporting does affect the perception of the honor system overall.

This past January, the Committee formed a working group that works to increase dialogue between Committee representatives and non-Committee members of the community.

Through the group’s outreach efforts, Behrle has found “people believe in honor — those ideas are easy to get behind, such as being good to one another, but they are skeptical of the honor system itself.”

Johnson spoke to the limits of past outreach efforts. He believes running for the Honor Committee or the University Judiciary Committee is not a priority for many minority students after the initial rush of first year. He said most choose to pursue leadership roles in minority activism groups like the Latino Student Alliance or the Black Student Alliance.

“You go into an info session for Honor, and it’s about 30 white people, two or three Hispanics, and maybe one black person,” he said.

But even Johnson agreed increased outreach is a solution.

“I want to talk to people and make them think, ‘I might be an asset to the system,’” he said. “Gradually, I hope to change the organization to reflect the student population. Until that changes to reflect different viewpoints, the system will continued to be flawed.”

In contrast to Honor’s perceived bias, the UJC’s reporting rates are more comparable to the student population. All of the 39 cases filed in fall 2013 were filed by University officials. Only two were filed against African-Americans and four against Asian-Americans, though race data was not available for all cases. White Americans constituted 62.1 percent of those accused among cases with race data.

UJC Chair David Ensey, a fourth-year Engineering student, attributes this to the Committee’s more objective standards for reporting offenses. UJC reports come mostly from deans and residential life officers, “and the standards for evidence removes an element of subjectivity,” he said. In terms of representation, Ensey felt the Judiciary Board reflects the demographics of the student population.

“We have empty positions for the Judiciary Board some years, and if I were to explain why, race is not the first place I would look,” he said.

Johnson said he was somewhat pleased with the direction student leadership was going in terms of minority leadership, believing it would lead to greater minority participation.

“It’s important to have Tim Kimble [on UJC] and Jalen Ross in [Student Council],” he said, referring to the third-year College and Engineering School students, respectively, who both identify as African-American.