As a philosophy major, East Asian Studies minor and resident of the Japanese floor of the Shea House, I have dedicated a good amount of time to studying Japan and its culture. Now entering three weeks into my three month summer stay in Japan and I have learned no matter how much you study a culture at home or in a classroom, it’s not the same as being immersed in it. For me, this feeling is best exemplified by something my friends and I like to call “the gaijin stare.”

Gaijin is the Japanese word for “foreigner.” It’s short for “gaikokujin,” which is the politically correct way to say the word. Gai means “outside,” koku means “country” and jin means “person.”

Gajin is what Japanese people call me or anyone else who is not strictly Japanese. Japan, by some metrics, is one of the world’s most ethnically homogenous countries. Gaijin are something of an anomaly here, particularly in the small countryside town of Hitachi, where I am doing my three month internship.

The gaijin stare is just what it sounds like. Japanese people walk down the street and, surprised to see a foreigner, cannot help but stare as they walk by. These gazes range from a prolonged glance to flat-out staring — sometimes coupled with turning around after you pass to continue watching.

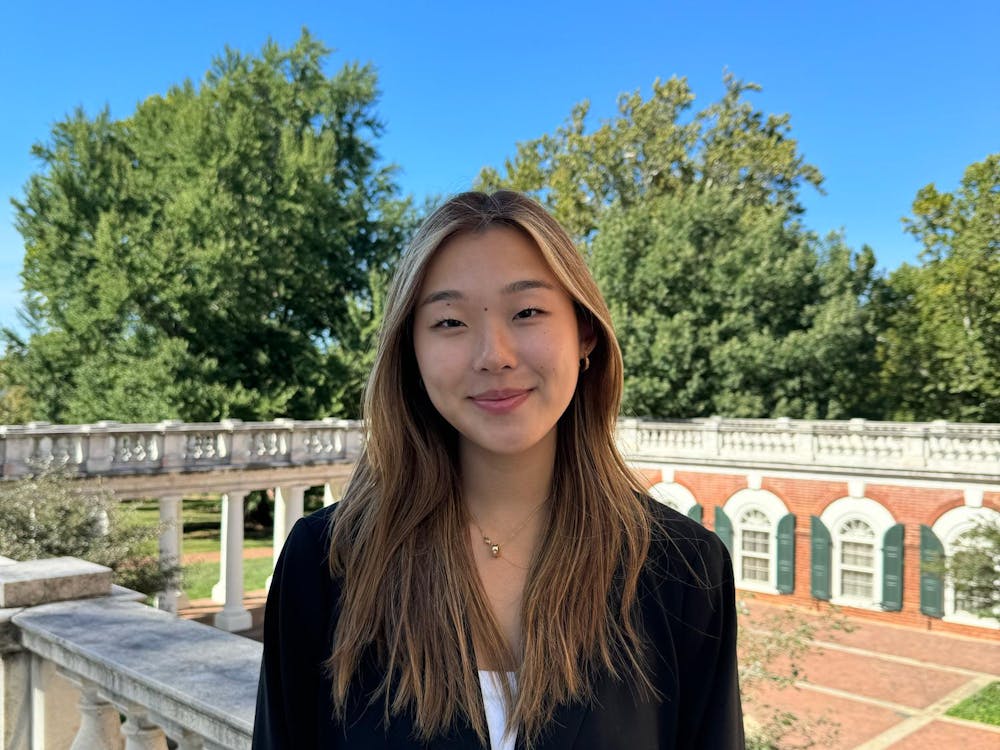

Before coming to Japan, I had heard about the gaijin stare. I was fully expecting it; after all, I’m a six-foot-one white girl with light brown hair and no shortage of curves — basically the antithesis of a typical Japanese woman. I knew it was coming, but I never expected how it would feel.

At first, it was almost cute — I was amused. But it quickly lost its appeal, and I’ve had to come up with ways to avoid the stares. Wearing a hat or sunglasses does not work, since my body type alone is a dead giveaway. Sometimes I find staring back gets many people to stop, but this is even more uncomfortable on my end. My favorite tactic lately has been to give someone a wave and say, “konnichi wa!” This has the dual advantages of stopping the uncomfortable staring and remaining polite and friendly.

But still, some mornings, I groan at the realization that I have a 20 minute walk to work while fighting through both the busy foot traffic and the stares of everyone on the street. There is something deeply uncomfortable about walking and finding yourself subjected to the gaze of each person who walks by, and every driver stopped at the light as I cross the street.

This experience reminds me of a phenomenon I studied in a course on American race relations — “the white gaze,” which in part involves white people in America staring at black people in areas where they do not expect to see any black people.

When I took the class, I had no understanding of how it felt to be under the white gaze. I could sympathize, I could say how it must be horrible and I could keep it in mind so I would not do it myself, but I had no idea what it felt like. Now I have a better sense.

Though the gaijin stare and white gaze are not completely the same, my experiences in Japan have afforded me an important ability to empathize.

I didn’t expect traveling to Japan to offer insight on American race relations, but I’m glad it has. So many Americans are completely unfamiliar with what it feels like to be silently and persistently singled out. Throughout the next two months, I hope I will be able to further deepen my understanding of those who are different and teach me about ways to foster social movement in a more positive direction.