As per tradition, the Black Student Alliance, Collegiate 100 and National Pan-Hellenic Council had a first home football game kickoff on the Lawn. This year, it wasn’t particularly difficult to decide where to have it — Room 1 West Lawn is the only one occupied by a black student.

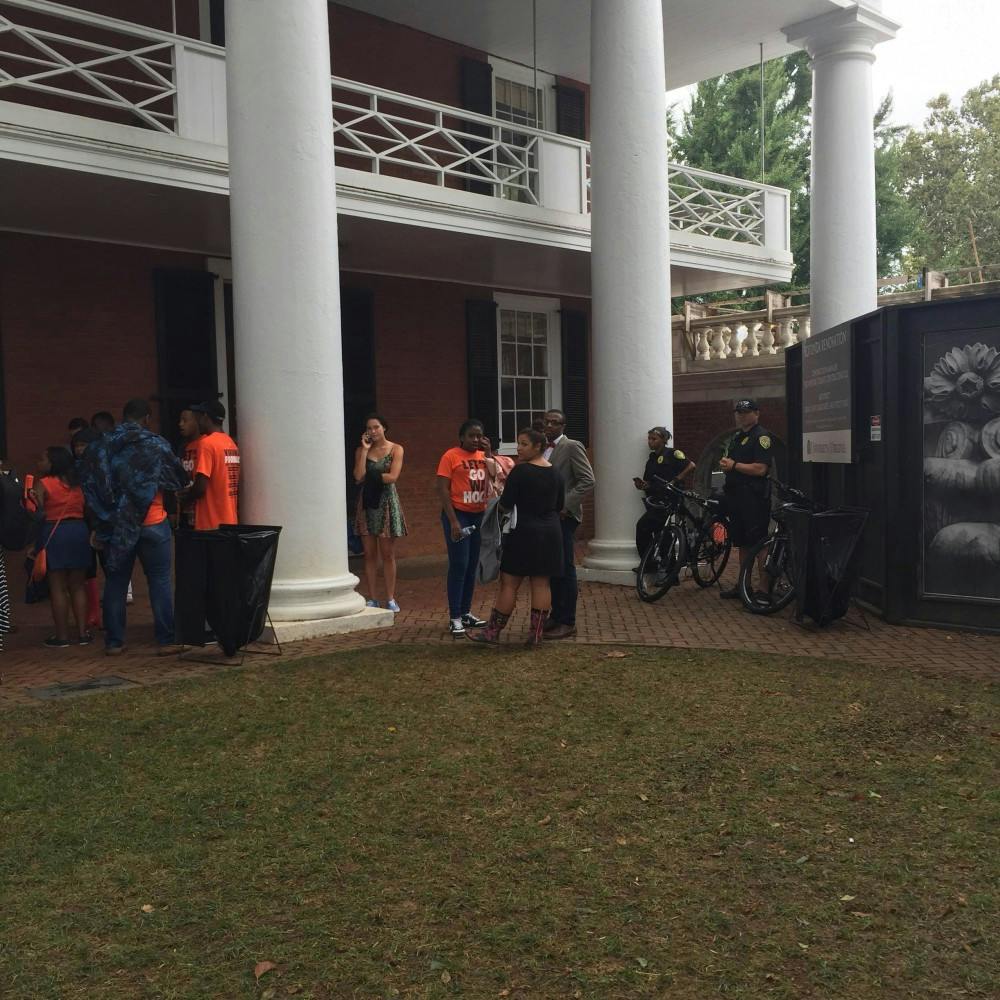

With music playing in the background, we gathered with burgers, hot dogs, chips, water, juice and soda from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m., and, like clockwork, two University police officers arrived not long after us. I looked on in annoyance — naturally, the only mass of blackness on the Lawn would attract police attention. I spoke to others; they had already noticed the officers, and were also unsurprised — the tense resignation on students’ faces was clear: police always seem to find their way toward black spaces. I wondered to myself, and then to a friend nearby, whether officers were stationed all around the Lawn.

We took a walk to check. I saw masses of people drinking, many with open containers and without wristbands, thus violating the gameday regulations; I did not see another officer other than the ones who still stood angled at our gathering.

Melissa Fielding, law enforcement captain of the University Police Department, explained in a phone conversation that officers’ primary responsibility was to ensure compliance with laws and regulations. Fielding, who apologized if these officers “created an issue” for our event, expressed on behalf of the officers who had been on the Lawn that those two officers had chosen their location to have a fuller view of the Academical Village. But perhaps if these officers had moved, they would have been, as I was, made privy to the many policy violations they were there to catch. Unfortunately, they didn’t move to look over the rest of the Lawn until almost 2:30 p.m., when the senior resident of the Lawn, after hearing from myself and the Room 1 resident that these officers had not once moved, went to speak with them.

Let’s be clear: over-policing of black bodies is nothing new — in fact, in regard to policing in Virginia, there is little older. Slave laws were some of the earliest laws in the state of Virginia,

and following emancipation blacks were targeted by vagrancy and Jim Crow laws, convict leasing practices, and the vigilante “justice” of lynching. It would be remiss of me to say that two police officers loitering at a BSA, Collegiate 100 and NPHC gathering on the Lawn has the same severity as the aforementioned, but it is in the same vein, and stems from the same place: a desire to keep surveillance on black people; a desire that has been so long held that, for many, they do not even realize the historical tradition that they are following.

That historical tradition continues in the over-policing and restricting of black bodies all over the University. All one need do is consider that, somehow, police officers always seem to find the one majority-black party taking place on a weekend night in a private residence, but rarely, if ever, dare shut down a party on Rugby Road, or Wertland Square. A lot of hypotheticals can be made for why police officers always happen to stumble upon black spaces, and somehow manage to avoid white ones when we talk about social spaces, which is what makes the situation on the Lawn particularly telling.

As I walked down the Lawn, hoping for a single glimpse of a University Police Department uniform anywhere else in the Academical Village, I was frustrated by the contrast I saw. We had purple wristbands and red solo cups at our gathering being enforced for those who brought their own alcohol; for our part, all of the drinks we provided were non-alcoholic. Around the rest of the Lawn, there were piles of empty beer bottles strewn across the sidewalk and grass, but no officers anywhere close by to see them. If the true goal was to keep order and ensure compliance on the entire Lawn, then there was no rationale for officers to idly and only stand outside of our event.

If we are going to have policing, I am a fan of consistency. I am a fan of logic. I am a fan of equity. It is not consistent to shut down the one or two majority black parties on a given weekend that take place far from the Corner, but to avoid policing areas we know are hotbeds for loud music and rampant underage drinking (so much, in fact, that I would venture to say that there are more underage drinkers every weekend in these predominantly white spaces than the 927 total black undergraduates attending the University, as of last year). It is not logical, if one’s assignment is to watch over the entirety of the Lawn, to post up 10 feet from a majority-black gathering, yet never even think of patrolling the rest of the Lawn until its SR asks more than an hour later. The way that policing, restricting and surveilling of action occurs at this University is not equitable, and often times, poorer and darker people fall on the wrong side of this inequity.

Officers need more parity in their policing efforts. Certainly, they should not only police black spaces when there is a myriad of numeric and anecdotal evidence that crimes are being committed in much higher numbers elsewhere. Not only are such practices inconsistent, illogical, and inequitable — they inch dangerously close to illegal.

Aryn Frazier is a contributing writer for The Cavalier Daily and Black Student Alliance’s bi-weekly “What’s the Word” column.