At the start of this academic year, University students received links to complete two educational modules. The first was the Alcohol-Wise program the University has used in the past to educate students about alcohol and drug use. The second was a new program titled, “Not on Our Grounds: Sexual Violence Education Module.” According to the email sent out by Dean of Students Allen Groves, the module was “designed to educate [students] on conduct prohibited by the University's Policy on Sexual and Gender-Based Harassment and Other Forms of Interpersonal Violence, and inform [students] of ways in which we all can serve as active bystanders.” Groves also noted the module satisfies federal requirements for universities to provide training on the topics covered (sexual assault, stalking and relationship violence).

Grouped in the same email with the Alcohol-Wise program, the module elicited much of the same frustration from students as Alcohol-Wise. Both programs are mandatory. If students do not complete them by a certain date, they temporarily lose access to online services like their University email and Collab, often needed to complete homework. While this policy ensures that all students complete the programs, it also turns them into another box to check, an annoyance to get out of the way. I have heard many complaints from my peers about the uselessness of the module, which Dean Groves estimates should take about an hour and 15 minutes to complete. Such complaints generally focus on the fact that students feel the module won’t really be effective in curbing the behaviors it warns against. With these student frustrations in mind, I sat down to complete the module myself.

I found some value in parts of the module. The various sections lay out clear definitions of terms like stalking and sexual assault, include links to University policy and list resources that students struggling with any of the given issues can use. These elements may be helpful to students who have dealt with such issues, as well as students who simply don’t understand what sexual violence (and other terms discussed in the video) mean. That said, I was struck by how difficult it might be for a survivor of sexual assault to complete this module. The speakers in the opening video acknowledge that problem, telling students to “complete the module as best you can,” and to seek help from the given list of resources if they need it.

I knew many students were eager to complete the module as quickly as possible. As I was completing it, I found the majority of the videos were easy to skip entirely, and most sections could be clicked through quickly without actually reading or listening to any information. One of the most important portions of the module was how it required students to read University policy on sexual violence and related issues. However, the button to acknowledge that you had completed the reading was placed at the top of the screen; I didn’t even have to scroll through the policy to find it. The University can now be about as sure its students have an understanding of sexual violence policy as iTunes can be about whether its customers have read their terms and conditions.

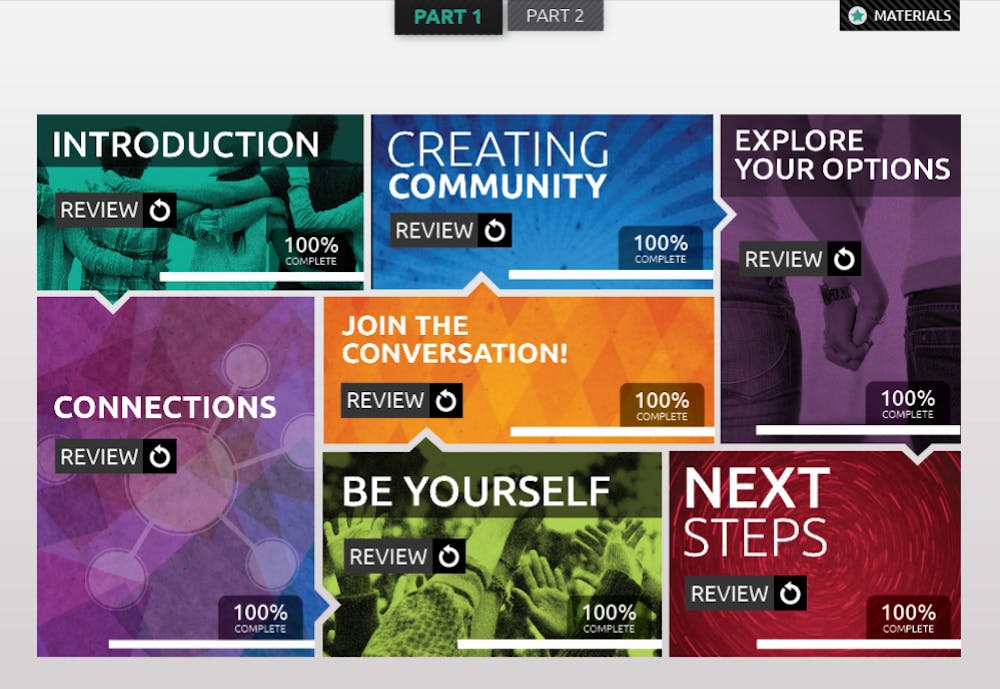

Of course, it is the responsibility of the student to commit to learning about such important issues. But a module that takes over an hour to complete and includes activities like “Spin the wheel of bystander intervention tactics!” isn’t likely to appeal to many students, even those who care deeply about the issues at hand. Elements like the click-and-drag activities make it feel more like a lesson I would have been asked to complete in my middle school health class than a way to address a serious problem on a college campus. As I clicked through the required videos and activities reminiscent of my sixth grade homework, I could understand why most of my peers saw the module as an annoyance to get out of the way.

Still, I found nothing inherently problematic in the module. It’s never bad to get students talking about such important issues. But I hope administrators won’t treat it as a bigger help than it is. I didn’t come away from the module feeling any more educated or ready to deal with the sexual violence that plagues college campuses. Perhaps the module provided some feeling of security for first-year students, who are likely to have heard stories of the dangers of sexual violence in college. That feeling of security cannot have lasted long. University students received two emails reporting issues of sexual assault or misconduct in the first week of school; I doubt this module did much to help the students involved in those incidents. The module started off with a video about the program, which included a sunny yellow screen where the words, “It’s time for a change, and it’s happening on campuses across the country,” scrolled across as cheerful music played in the background. I hope a change is happening, but I haven’t seen it yet, and I don’t think the University can expect much of it to come from this module.

Nora Walls is an Opinion columnist for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at n.walls@cavalierdaily.com.