Lights came on, painstakingly slow, emanating from the figure’s shoulders, head and torso rather than from the bulbs above. Audience members waited expectantly, anticipating the rise of music and sound as the man burst into movement, but it didn’t come right away.

One of the most poignant moments of the Abraham.In.Motion showcase this past weekend was the silent beginning of a piece called “The Quiet Dance.” The silence saturating the air and pressing against the audience complemented the choreography almost disconcertingly. Not a cough or throat-clearing broke this moment, frozen but for the dancers contorting their bodies into noiseless shapes. The gradual incorporation of piano notes further enlivened the dance. All five dancers — Kyle Abraham, Matthew Baker, Catherine Ellis Kirk, Tamisha Guy and Jeremy “Jae” Neal — participated in this first piece, though they represented only five of 12 total dancers in the company.

“The Quiet Dance” emanated hope. It highlighted ideas of interpersonal connection, helping one another and trying to break free from the confines of one’s own mind and society as blockades purposely placed to restrain or limit people.

The second dance, an excerpt from “The Gettin,’” featuring a duet by Baker and Neal, presented tension, uncertainty and a heated display of power, conflict and struggle between good and bad, social expectations and internal desire to disregard the norms. The subsequent excerpt from “The Watershed,” a solo by Kirk, evoked desperation and yearning to understand and cope with everything happening around her. “Hallowed,” a piece by Guy, Kirk and Neal, presented a segment of meditative and technical movements in which each of the dancers worked together to share their struggles and triumphs.

The final piece, full-length work “Absent Matter,” was performed by all five dancers and offered a very different feel than the first half of the show. The music and design contrasted sharply with the other pieces, though the show still collaborated and worked as a unified whole. Abraham stated he “was so frustrated… [he] wanted to focus on something that was more current and make something that was a little bit angry.”

Despite the pieces and excerpts taken from various different works, everything related and seemed to be part of a single project. Videos, images and textual supplements helped connect everything and encouraged audience members to form unique interpretations of their individual experiences.

Explicitly narrative sections interspersed with ambiguous choreography enhanced the dynamic performance. Intimate interactions created clear stories, but did not hinder the overall production. The cumulative effect of dance and media was overwhelming at times, but the historical, political, social and personal stories were clear.

Lapses in sound and movement drove much of the storytelling. “The reason we move as fast as we do is so the stillness can be highlighted,” Abraham said.

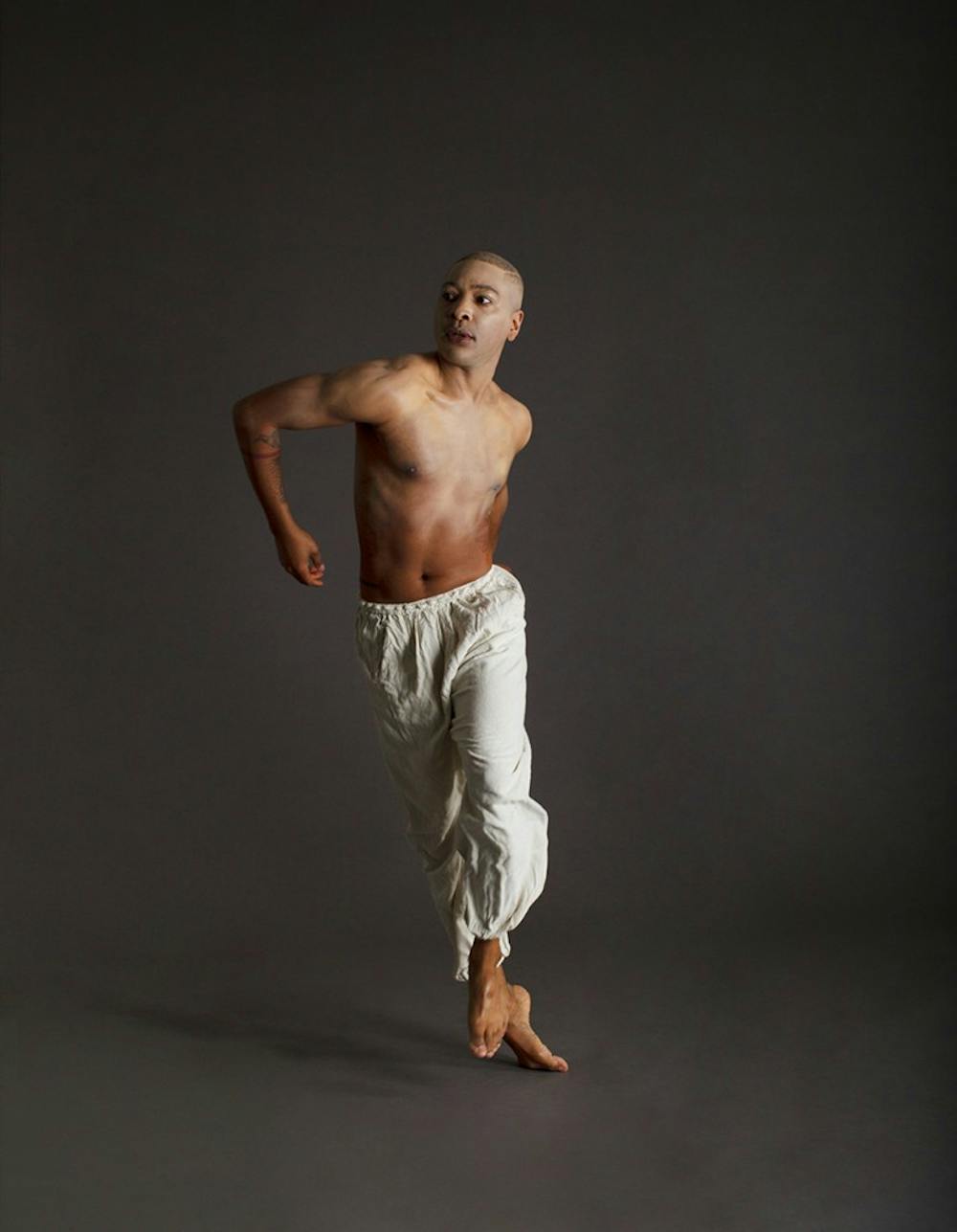

Neal followed up, saying, “Fast moving is something I do without even really trying, but I activate my body and my mind when I’m completely still.”

Music notes jerked bodies and guided movements, dictating the motions before the dancers themselves seemed to know. The movements mimicked the music at times, while at others they diverged in spontaneous bursts of energy or stillness. Alternations between fluid motions and abrupt breaks in the continuity of the choreography helped define the dances.

The dancers made their performance seem easy and effortless — yet there were moments when audience members saw calves shaking slightly and chests racing, subtle indicators of the effort and energy put into the works. These idiosyncratic hints offered a more genuine, human experience where dedication and work clearly paid off on stage.