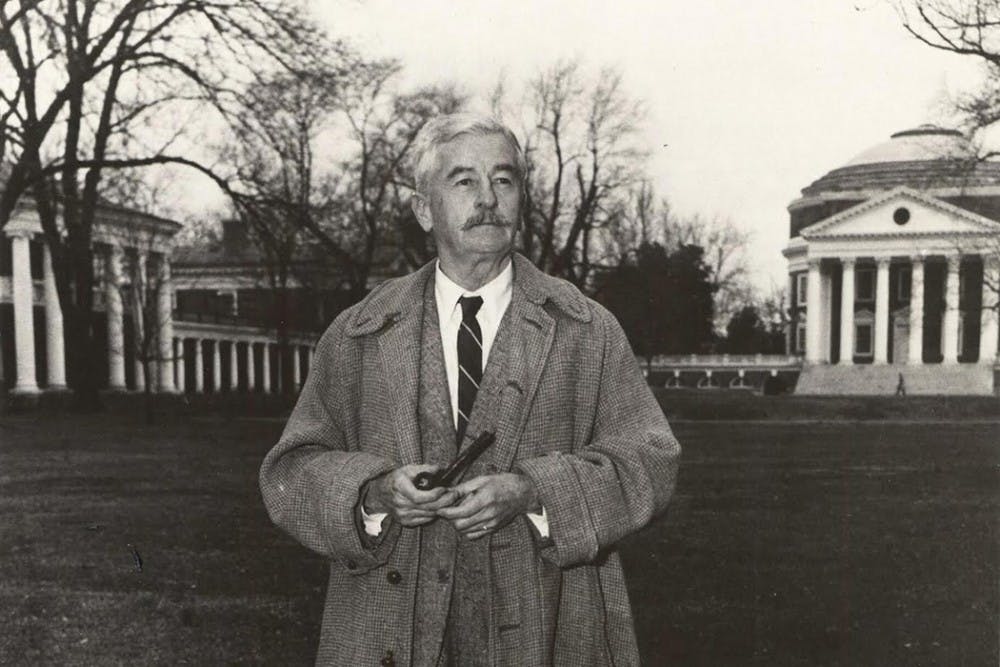

As Junot Díaz finishes his time as the University’s writer-in-residence, the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library winds back the clock 60 years to highlight the first writer-in-residence at the University — the prolific and enigmatic William Faulkner. “Faulkner: Life and Works” is an immersive exhibition detailing the author’s history both on- and off-Grounds. The exhibit opened Feb. 6 and will remain open to the public until July 7.

One of the most prominent components of the exhibition is a display containing copies of a number of Faulkner's more-famous novels. First editions of each work paired with brief summaries of the fiction and, in some special cases, handwritten manuscripts of the novels’ first drafts fill a large case in the center of the small room.

Even for those unfamiliar with Faulkner’s work, there is something thrilling about seeing the first efforts of one of America’s best known-authors, painstakingly written out in dark blue print. An added layer of interest is that some of these manuscripts were written while Faulkner was the writer-in-residence at the University — from 1957 until his sudden death in 1962.

Surprisingly, the only lacking element of “Faulkner: Life and Works” is a more in-depth exploration of the author’s time at the University — most of the exhibition focuses on his life before his residency. Faulkner only visited the University in the twilight of his life when nearly all of his major works had already been published. As a result, the exhibition feels more like a celebration of Faulkner as an author rather than an examination of Faulkner within the context of the University.

It is tempting to claim Faulkner as one of the University’s own, but the school’s role in his life was tangential at best. Much the same is true of Edgar Allan Poe — despite the mini-museum on the Range and the (now-extinct) Eddy’s Tavern, Poe spent less than a year at the University and spent a good chunk of that time accruing massive gambling debts. The University has a residential community named after Faulkner, but the degree to which the man and the school really influenced each other is a question not answered by the exhibition.

The exhibition succeeds in providing an exhaustive, engaging inspection of the most recurring and important themes in Faulkner’s work. Perhaps the most relevant of these — both when he was alive and to this day — is race. Accordingly, the exhibition has an entire case dedicated to explaining Faulkner’s conflicted ideas about the issues of slavery, Jim Crow laws and segregation.

Race was inextricably tied to Faulkner from birth — named after his great-grandfather, a Confederate soldier, Faulkner was raised on stories of the Civil War. In his novels, he adopted what was seen as a middle-of-the-road approach to the issue of slavery that alienated his fellow Southerners but underwhelmed the more progressive North.

According to the exhibition, he described slavery as the South’s “founding sin,” but he also criticized the North for failing to consider the perspective of the financially ruined Southern states. These dichotomies — slavery and freedom, wealth and ruin, morality and depravity — occupy some of Faulkner’s most famous stories and haunt his most unforgettable characters.

Despite its minor shortcomings, the exhibition does a wonderful job of shining light on Faulkner’s deep and remarkable wisdom. The best encouragement to attend is to provide a taste of that wisdom, which the exhibit features in the shape of a quote from Faulkner’s 1950 Nobel Prize speech.

“I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail,” Faulkner said in the speech. “He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet's, the writer's, duty is to write about these things.”