Thomas Jefferson’s primary plantation, Monticello, is currently undergoing restorations meant to better reinforce the infrastructure and include the lives of the many enslaved people who worked and lived on the property, including Jefferson’s alleged mistress, Sally Hemings.

The restorations are being made under the direction of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which owns and operates the property.

Despite all the recent press involving the restoration, the current projects are actually not the first time the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has worked on the property. The current restorations are all part of the larger initiative called the Mountaintop Project, which started in 2013.

The Mountaintop Project is estimated to cost $35 million in total, with a large portion of this budget to be spent on infrastructure improvements below ground. This part of the restoration will go unnoticed by visitors, but will allow Monticello to be sustainable for years to come.

Gary Sandling, vice president of visitor programs and services at the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, said the goal of the project is to restore Monticello and the surrounding landscape to better represent the property the way Jefferson would’ve known it.

“This component that has been in the news lately is to restore structures that are in the south wing of Monticello — living and working spaces where Monticello took slaves [and] where families labored and lived,” Sandling said. “The intent is to really restore something of a full context of Monticello, not just as a neoclassical house or architectural wonder, but to restore the context of Monticello as a plantation.”

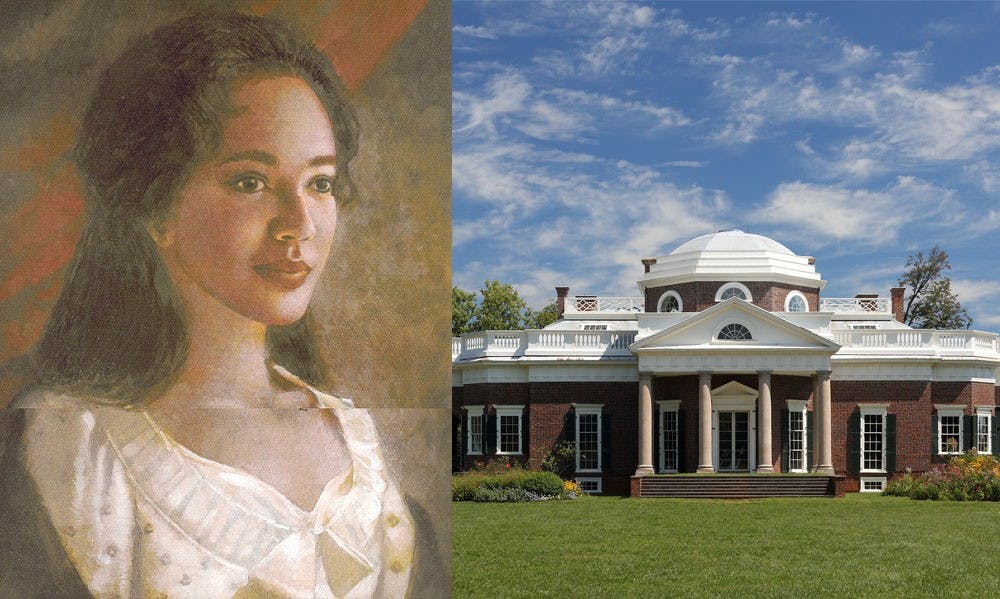

Along with reconstructing buildings where enslaved people worked, one specific goal of the project is to better include the life and presence of Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman who lived and worked at Monticello. Many historians believe Jefferson fathered Hemings’ six children.

“Historians at Monticello have been researching the enslaved community since the 1950s when archaeology first started along Mulberry Row,” Niya Bates, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation’s public historian of slavery and African-American life, said in an email to The Cavalier Daily. “For us, it's critically important that we talk about all of the enslaved families at Monticello, although the Hemings family is probably the best-documented enslaved family in the U.S.”

In the past, Hemings has often only been thought of in an objectified, sexual way, Sandling said.

“Part of the goal here is to restore her personhood — to think of her as a mother, to think of her as a daughter, to think of her as someone who had many relatives that worked at Monticello as well as relatives who were free that lived in Charlottesville,” Sandling said.

While most of the physical evidence of Hemings’ presence has been destroyed over the years, Monticello historians, researchers and archaeologists have been able to find evidence and clues in the south wing chambers which will allow them to restore a small room — where historians believe Hemings lived — with historical accuracy.

“Our archaeology and restoration teams have recovered a lot of information during the process, like finding pieces of ceramics and physical evidence of how the space changed over time. This allows us to have pretty accurate information about restoring her quarter in the south wing,” Bates said.

Sandling also said any time race and slavery is brought up in the context of an early American historic site, there will always be people who say Jefferson’s relationship with Hemings is being overemphasized or that the Founding Father is being denigrated.

“We think that knowledge from this comprehensive picture is what provides people a real opportunity to reflect on the founding era and upon Jefferson and his contributions, but also the contradiction — sort of paradox — of a nation founded on principles of freedom and liberty, but one that [also] continued to maintain the institution of slavery,” Sandling said.

Walt Heinecke, an associate professor in the Curry School, said he thinks the current restorations of Monticello and the honest dialogue on Jefferson and slavery have the ability to help people move beyond the issues of racism in the current controversial context of his legacy.

“Jefferson and race is an opportunity for the University to take leadership in grappling with the problem of race in the United States now,” Heinecke said. “I see it as a great way [that] the University could embrace the notion of Jefferson as a progenitor of racial superiority and then turn Jefferson on his head in terms of thinking how could the University become a leader in undoing the problem that he actually created.”

Heinecke said he believes the only way to reconcile influential ideals about democracy and Jefferson’s background with owning slaves is to acknowledge it.

"Once you acknowledge the dark side of Jefferson, you can go about reconstructing a response to that dark side of Jefferson that is constructive,” Heinecke said. “In other words, it can be used as a guiding point, or a point to start a really difficult discussion about race, racism, reconciliation, repair, reparations and those kinds of things.”