The field of eugenics — commonly discredited as a pseudoscience — has deep roots at the School of Medicine. Pinn Hall, was previously named after Harvey Jordan, former Dean of the Department of Medicine. Jordan was a prominent eugenics researcher and a renowned leader of the national eugenics movement.

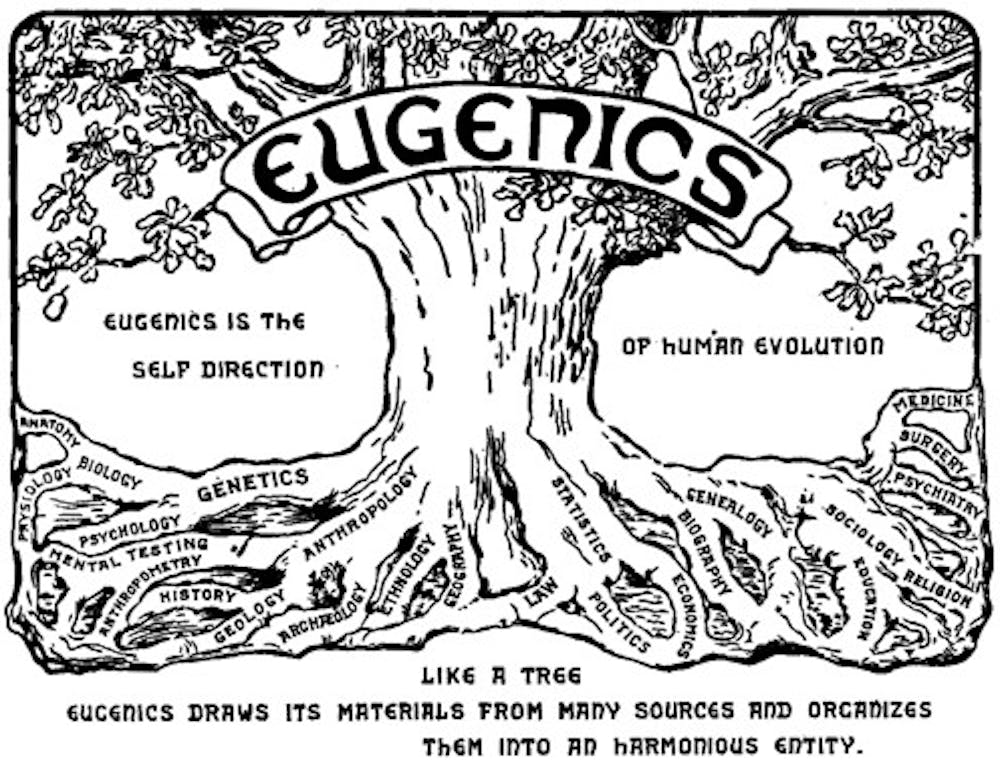

Popular in the early 1900s, eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices that aims to improve the genetics quality of the human population by deeming certain humans as genetically superior to others. Eugenic theory amplified segregation regarding race, class and disability across the U.S.

The attention garnered in the field led to Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Law in 1927, which attempted to forcibly sterilize those believed to be more inferior than others. Populations most affected by this law included poor and uneducated African Americans and other minorities.

The pseudoscience was taught at leading universities like Harvard, Cornell, Columbia and the University. Research in these institutions centered around data collection for the heritability of traits such as familial mental disorders and criminality, classifying some traits as far superior than others. Researchers would then use their data to provide evidence that certain individuals should not have children so as to inhibit the transmission of undesirable genes.

The popularity of eugenics drew then-University President Edwin Alderman to hire Jordan and Robert Bean to conduct research on eugenics at the University.

However, the renaming of Jordan Hall to Pinn Hall finally erases the small remnants of the University’s little-known association with the study of eugenics.

“The renaming of Jordan Hall as Pinn Hall was really about looking ahead — as we get ready to celebrate U.Va.’s bicentennial — to identify someone who embodies the attributes the students in the School of Medicine aspire towards,” Eric Swenson, University Health System Public Information Officer, said.

Vivian Pinn matriculated at the School of Medicine in Fall 1963 — a time when white men dominated its composition. When Pinn entered the auditorium on her first day, she soon realized that she was the only female and the only African American student.

“There were no other women or people of color in the class,” Pinn said. It was a very strange feeling — I can still remember that.”

At first, Pinn said she felt discouraged and considered abandoning her studies. But when two of her classmates invited her into their anatomy lab group, Pinn felt included and ended up staying, eventually graduating from the School of Medicine.

“That was the gesture that two of my classmates made that kind of got me involved in the class and prevented me from feeling like an outsider,” Pinn said. “That was a kind introduction for me, and I often talk about that since it was a gesture that made a difference in my life.”

However, Pinn faced challenges for being different. When obstacles arose, Pinn refused to give up but reminded herself that she was at the University for a reason — to be a physician. Pinn advises others facing adversity to remind themselves of their own purpose for pursuing a task, just as she did.

“It was just knowing that I was there for a purpose, and I had come so far that I wasn’t going to let anyone keep me from doing what I could do,” she said.