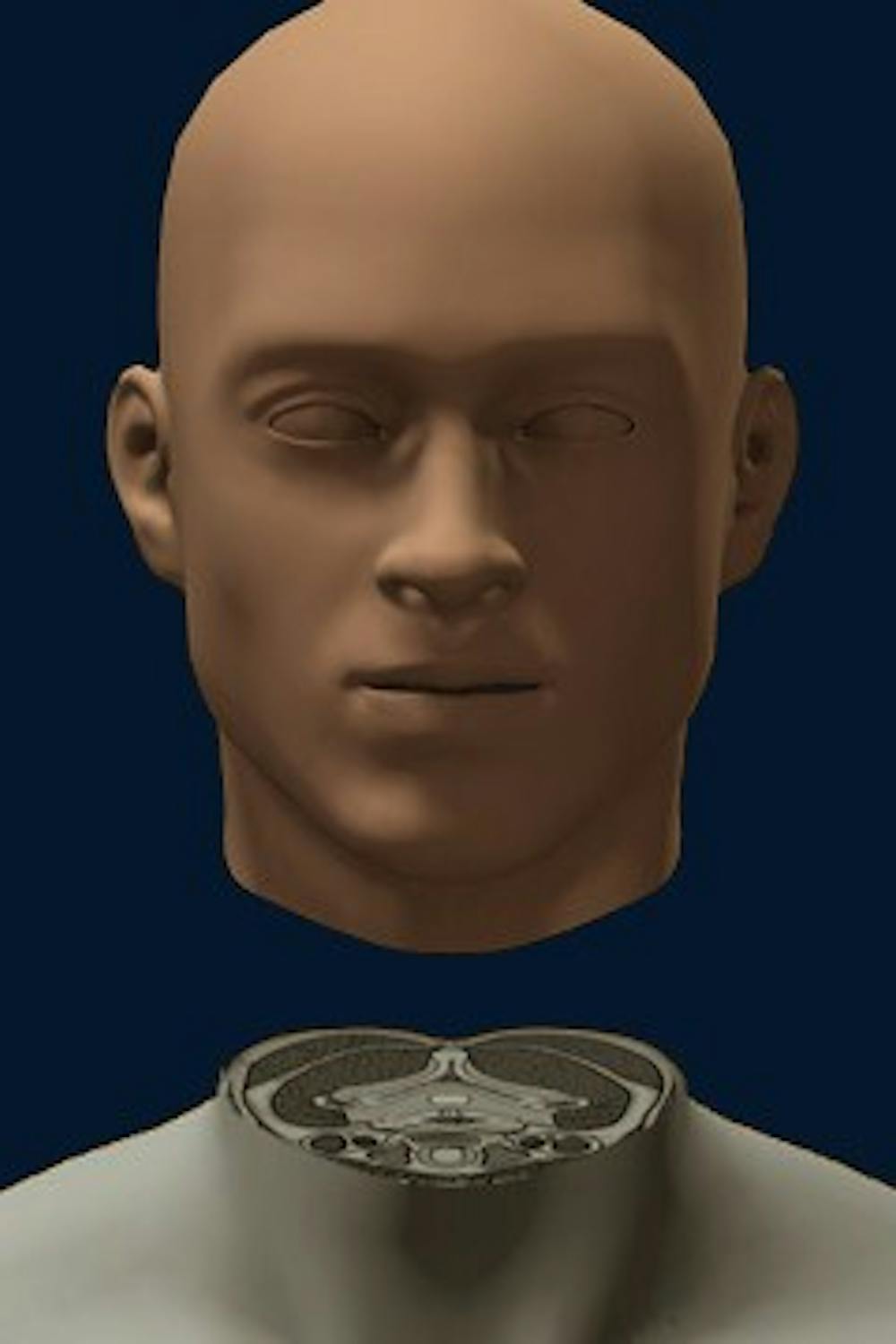

If approved, the world’s first human head transplant will be performed, by Italian neuroscientist Dr. Sergio Canavero in collaboration with Chinese surgeon Dr. Xiaoping Ren by December 2017. Valery Spiridonov — a 30-year-old Russian man who suffers from spinal atrophy and motor neuron degeneration due to Werdnig-Hoffman disease — has volunteered himself for the procedure.

Canavero has published a detailed surgical plan for the head transplant in the medical journal Surgical Neurology International. This plan, nicknamed “head anastomosis venture” (HEAVEN), includes a blueprint for what would be a 36-hour operation involving at least $10 million and 80 other surgeons.

The transplant begins with anesthetizing Spiridonov and cooling his body to 50 degrees Fahrenheit, delaying tissue death in the brain. Then, the surgeon would decapitate both a donor body and Spiridonov’s body and simultaneously sever both of their spinal cords. Surgeons would then attach Spiridonov’s head to the donor’s neck, binding the two ends of the spinal cord using polyethylene glycol. Thereafter, muscles and blood supply from the donor body would be connected to Spiridonov’s head while Spiridonov is placed in an induced coma for about a month. Electrodes would also be implanted to promote new nerve networks and growth.

Despite being a calculated procedure, Canavero’s plan is not immune to risks, including those inherent to all transplant procedures.

“For any transplant to be successful ... You need to prevent the immune system from rejecting the organ because the recipient’s body will always realize that the new organ doesn’t belong in his or her person,” said Dr. Jose Oberholzer, director of the Charles O. Stricker Transplant Center at the University Health System. “You also have to prevent infections from occurring on the transplant after immune system suppression.”

As an unprecedented surgery, the head transplant requires even more complex organ and vessel connections — posing greater uncertainty than common transplants like those of the liver.

“In the case of the liver, you will have a total of three blood vessels to connect and the bile duct,” Oberholzer said. “But in the case of a head ... It would not just be the blood vessels. The airways would have to be connected. You will have to connect the pharynx to the esophagus. You have to provide the cranial nerves — nerves directly from the brain that allow for certain functions and reflexes — and you will have to connect, somehow, the spine. And that’s technically not possible today.”

Additionally, modern-day surgical techniques for organ transplants have not evolved significantly in the past decade, since current methods are effective and widely successful for the organs that are common transplanted. As such, Oberholzer suggests these prevailing techniques may not be sufficient to perform at the level of difficulty that a head transplant would require.

“The first difficulty is the pure technicality of it. We have no technology to be able to fuse the spine — to make a spine that is separated regain function,” Oberholzer said. “The second is that there are just so many connections to be joined. The complication rate is just going to be tremendous — you can have leaking airways, a leaking esophagus, or if your saliva is flowing into either of those, or vascular vessel anastomosis. So the risk of infection is going to be very high too.”

Oberholzer predicts the probability of a successful head transplant is highly unlikely, if not impossible.

“You’re going to have, essentially, a brain completely disconnected from everything else,” Oberholzer said. “You may have a locked-in person who is kind of alive, but cannot move anything, cannot feel anything. It’s just a terrible thought.”

Beyond the anatomical and physiological analysis of the procedure, ethical issues also arise from the prospect of a head transplant.

“Access to scarce organs is a huge concern when it comes to transplants,” Asst. Bioethics Prof. Sahar Akhtar said. “Who gets put to the top of the transplant list, who receives it and why, are their bodies otherwise in good health and shape to merit giving it to them as opposed to, say, a younger person … These are your ordinary, run-of-the-mill concerns for transplants for critical organs — things like hearts and kidneys and livers.”

Specific to a head transplant, however, is the question of identity.

“There is literature that suggests that the mind is not all in the head,” Akhtar said. “There is a strong interplay between anything in the head and the full body and how the body reacts and responds to its environment. If the surgery was successful, would this be the same person, would they reserve their identity — and that requires saying a lot more about the nature of mind and body and the relationship between mind and body.”

In considering moral and ethical problems, Oberholzer relates the head transplant to “The Modern Prometheus” — Mary Shelley’s novel that is commonly known as “Frankenstein.”

“The line between Frankenstein and science becomes very blurry,” Oberholzer said. “It’s a nightmare scenario if you think about it.”