Del. David Toscano (D-Charlottesville) introduced a bill last week to the General Assembly of Virginia, calling upon delegates to revise the code on memorial and monument removal. The current Code of Virginia, 15.2-1812, makes it unlawful for authorities or any other persons to remove the erected monuments or memorials of war conflict.

“It shall be unlawful for the authorities of the locality, or any other person or persons, to disturb or interfere with any monuments or memorials so erected, or to prevent its citizens from taking proper measures and exercising proper means for the protection, preservation and care of same,” the law currently reads.

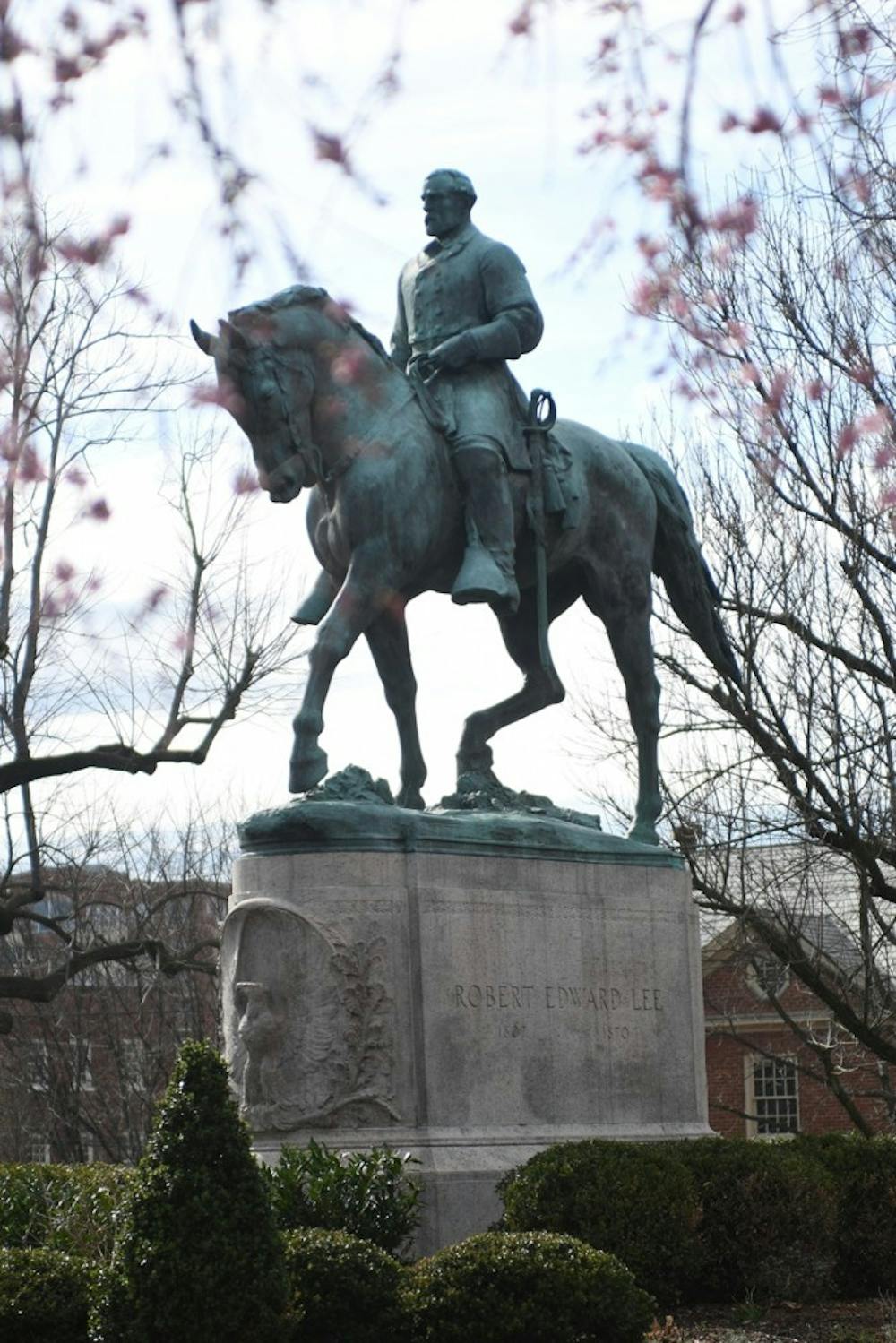

Professors at the Law School participated in the conversation, contesting the code earlier last year in order to legally remove the Robert E. Lee statue in Emancipation Park. Law Prof. Richard Schragger argued that the code did not apply to Charlottesville when City Council voted in February last year for removal of the Lee Statue. Just months later, in September, City Council voted to also remove the nearby Stonewall Jackson statue.

“The original statute — adopted at the height of Jim Crow — gave counties the authority to construct Confederate monuments and forbade their removal or destruction,” Schragger said in the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “But that statute did not say anything about cities. It neither authorized cities to erect monuments, nor prevented them from removing them.”

The battle over the Lee statue’s removal sparked a lawsuit against the city of Charlottesville, plaintiffs including the Monument Fund, the Sons of Confederate Veterans and several others. It also led to the “Unite the Right Rally” Aug. 12, where an Ohio man plowed his car into a crowd in downtown Charlottesville, killing one.

While there were disputes on whether local law permitted removal of the statues, the discussion spanned out to the federal level. Law prof. Micah Schwartzman argued the standing Confederate statues were unconstitutional by federal law and cities should not be restricted by local law to preserve them, but rather obligated to act for their removal.

“An implication is that the city of Charlottesville has constitutional grounds for challenging any Virginia law that prevents it from removing a statue that communicates a message of white supremacy,” Schwartzman said on Slate. “City council members have a sworn obligation to uphold the Constitution, and if they believe that the monuments violate equal protection as guaranteed by the Constitution, they have an obligation to take them down.”

However, the local legal battle against the city and over the Lee statue removal has seemingly just begun. Judge Richard Moore set a temporary injunction for both the Lee and Jackson statues in October, ruling that the 15.2-1812 war memorial statute did in fact apply retroactively to the Charlottesville statue.

“I think he could have read the statute to permit such removal, consistent with the Attorney General’s interpretation of the statute,” Shragger said in an email to The Cavalier Daily.

Through an advisory opinion, Attorney General Mark Herring interpreted the 15.2-1812 law in August last year as allowing some cities to remove Confederate statues, contrary to Moore’s interpretation. Despite Moore’s recent court decision, Herring questioned at the time whether the statue was indeed a war memorial, and if not, the law would not be applicable.

The Lee statue thus remains in its place, and the lawsuit drags on with the next hearing in early February this year. The Jackson statue, also part of the lawsuit, remains in its place as well.

“I think the judge will ultimately conclude that the Lee statue is a war memorial and will eventually order them to be uncovered,” Schragger said. “I think many Charlottesville residents and Virginians more generally will be dismayed by such a ruling. Perhaps more pressure will build to change the law in Richmond. Also, I suspect there will be an appeal to the Virginia Supreme Court.”

Toscano’s bill would channel the conversation from the judiciary to the legislative branch in Virginia. It amends the 15.2-1812 statute for a smoother process and would allow localities to remove and better contextualize monuments and memorials.

“White supremacists came to my city [Charlottesville] last summer and wreaked deadly violence in the name of a statue,” Toscano said in an interview with the Daily Caller. “My bill would empower localities to remove these statues if they so choose, or to keep them if they want to as well.”

Del. Charniele Herring (D-Alexandria) also submitted a bill supporting statue removal.

Whereas Toscano’s bill adds a clause explicitly permitting the removal of monuments, Herring’s calls for the construction of the Monument Removal Fund. The fund would help localities offset the costs associated with the removal or relocation of monuments, and contributions could be made via gifts or grants.

The removal of the Charlottesville Robert E. Lee statue cost the city nearly $5,000, only for shrouds, which have been used to conceal the statue in memory of the woman who died Aug. 12, Heather Heyer. The Lee statue remains at Emancipation Park, shrouded. Herring’s proposed fund would assist the monument removal process like the one the city of Charlottesville is confronting.

Neither of Toscano’s and Herring’s bills would restrict the erection of future memorials or monuments. Both bills would permit the controversial Civil War monuments to continue to stand and for new ones to be erected.

Both bills are awaiting committee referral.

Toscano and Herring’s offices declined to comment as of press time.