Catalyzed by the white supremacist rallies in August 2017, the City of Charlottesville has faced a reckoning for a wide variety of racial disparities. Among demands to address racial housing inequities throughout the city, several anti-racist and housing justice advocates are calling for a $50 million bond to fund affordable and public housing needs in the area.

Brandon Collins, a member of the Charlottesville Low-Income Housing Coalition (CLIHC) — an umbrella housing activism group — and the lead organizer of the Charlottesville Public Housing Association of Residents, said the proposal has far-reaching implications for addressing racial inequality in the City.

More specifically, Collins said the proposal comes at a time when many long-time African-American residents, notably those in the Prospect, Rose Hill and Fifeville neighborhoods, feel like they are being pushed out of Charlottesville due to gentrification and rising property taxes — and the affiliated rent hikes.

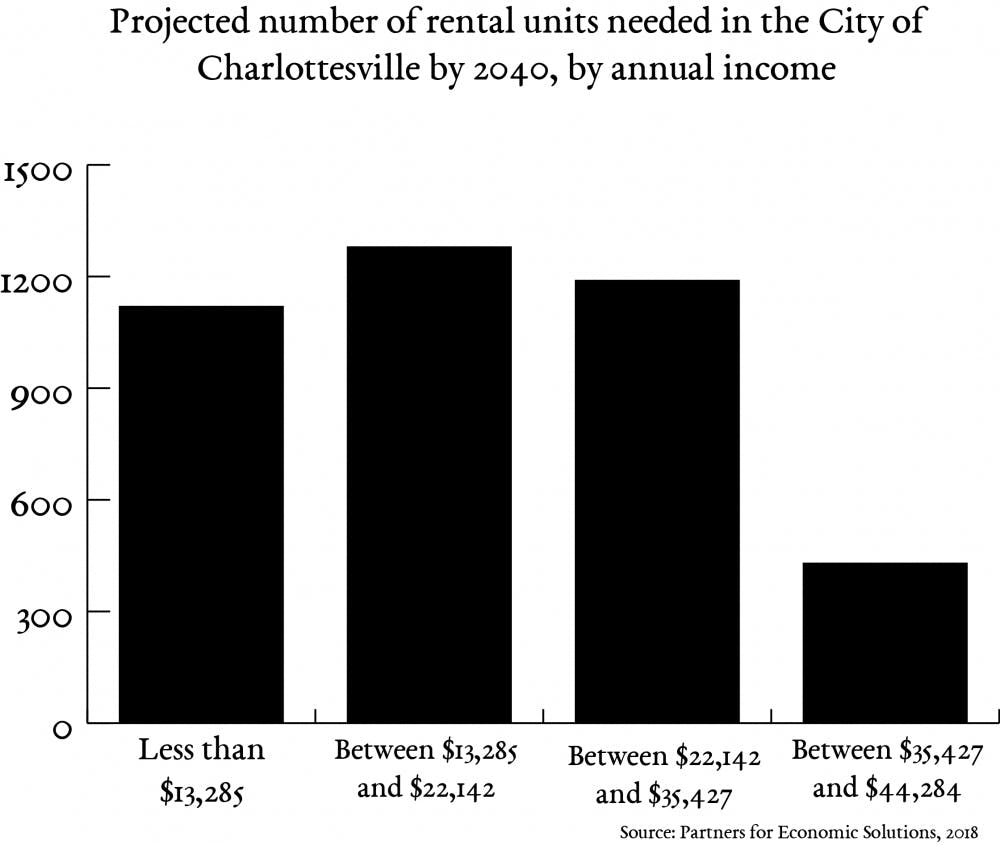

According to local housing experts, the proposed bond — with the purpose of redeveloping the City's existing public housing stock and the construction of affordable public housing in Charlottesville — would be a significant step in helping to rectify a long-term shortage of more than 4,000 affordable housing units in the City.

The scale of the City’s housing crisis

The addition of the nearly 4,000 affordable units by 2040 would satisfy the existing demand for low-income housing in Charlottesville. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, an “affordable” unit is one that a three-member family can purchase or rent for 30 percent or less of the area’s median income.

In the City of Charlottesville, the area median income is $44,284 and $60,047 in the encompassing metropolitan area, which includes Albemarle County as well as nearby Fluvanna, Greene and Nelson Counties.

At a joint work session between the City Council and the City’s Housing Advisory Committee last month, Ridge Schuyler — co-chair of the policy subcommittee for the HAC — said the average price for a two-bedroom apartment in Charlottesville has grown 27 percent, from $931 a month in 2011 to around $1,250 a month in 2018, adding that wages in the City have not kept up with the increase in rent rates. The national average two-bedroom rent is $1,180.

Schuyler added that 1,800 families, or 29 percent of families in the city, did not earn enough income to be self-sufficient — or without external financial assistance — in 2011. Meanwhile, more than 2,000 families, or 25 percent of families in the City, continue to earn too little to be financially self-sufficient.

Schuyler’s findings originate from research he has conducted locally during the past seven years as the founder of the Orange Dot anti-poverty project.

Households making under $25,000 annually — which includes these “extremely low-income families,” as defined by HUD — comprise approximately 30 percent of Charlottesville’s population and approximately 20 percent of the City’s encompassing metropolitan area, according to a Housing Needs Assessment commissioned by the City earlier this year.

Currently, the City is able to issue General Obligation Bonds — or those issued by a municipality with the backing of its own credit and taxing power — to finance City endeavors and school capital improvement programs. Such bonds are approved by the City Council with the passage of the City’s budget each fiscal year. The City has received a AAA bond rating since 1973.

However, at the joint work session between the Council and the HAC, Councilor Wes Bellamy said the Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority should also be given the power to issue bonds to renovate existing public housing units and purchase land for the construction additional affordable units.

Bellamy said this would allow for the CRHA to autonomously allocate funds to housing projects as it sees fit, given its greater expertise in the matter and connections to local organizations. However, other councilors expressed concerns during the work session with the CRHA’s limited credit rating to issue bonds as it has not previously done so in the past.

No members of City Council responded to requests for comment from The Cavalier Daily.

Finding funding for affordable housing

Edgar Olsen — an economics professor and housing policy scholar — compared the bond to a traditional loan, noting that the amount that would need to be paid back by the City of Charlottesville over time would be greater than the allotted $50 million due to interest rates.

“[Issuing the bond would require] either one of two things: either raise the tax rate and raise more tax revenue, or cut back on something you’re currently spending on,” Olsen said in an interview.

Olsen described the bond as “certainly feasible” in an economic sense, as the bond would serve to increase the amount of money allocated annually to fund affordable housing projects around the City.

Grant Duffield, the executive director of the Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority, also described the proposed bond in an interview with The Cavalier Daily as “entirely feasible” and one that should be “widely embraced” by the Charlottesville community.

“When you weigh it against the benefit that it provides our community, [$50 million] is a nominal investment in the well-being of Charlottesville for the future,” Duffield said.

During the September work session, HAC Chair Phil d’Oronzio said a very rough estimate of the amount of money necessary for funding affordable housing in the City by 2040 could be as much as $120 million, estimating that the 4,000 needed units would be valued at $30,000 each.

The City currently has 376 units of public housing and 720 units of housing funded by low-income tax credits — and 40 percent need to be replaced in the near future due to age and high maintenance costs, according to the Housing Needs Assessment.

Each year, HUD gives CRHA approximately $1.2 million from subsidies and $1.2 million in tenant rents. The City’s budget for the 2019 fiscal year also allocated $19.5 million over a five-year time period for redevelopment and construction of affordable housing. CRHA also receives $300,000 annually from the federal government, but Collins says the amount may decrease in the future.

At its Oct. 1 meeting, the Council allocated more than $2 million from the Charlottesville Affordable Housing Fund to several housing initiatives in the area. Currently, the CAHF has about $167,000 in funds remaining for the 2019 fiscal year.

Challenges to the bond and affordable housing policy reform

The current state of funding for these projects is insufficient according to Collins, as “tens of millions or hundreds of millions” are needed to provide an adequate financial solution to the City’s lack of affordable housing.

“The way you get that kind of money is by having a community conversation that prioritizes addressing the affordable housing crisis and redevelopment of public housing,” Collins said.

The nationwide public housing program was first initiated in 1937 following President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. Public housing as many Americans know it today began during President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society initiative, designed to be a short-term program that Duffield says is largely outdated in applying to today’s housing crisis.

“The thought was, ‘We’ll build public housing because there is a need for low-income housing, but we’ll address the root causes of poverty, eliminate those and we won’t have a need for low-income housing in the long term,’” Duffield said.

However, Olsen is skeptical about whether the bond would indeed have a strong impact on the City’s affordable housing scene. From Olsen’s viewpoint, this is because most redistributive policies — policies through which the government obtains money from citizens and redistributes it to areas where it sees fit — are conducted at the federal level, not at the local level.

“One issue is if it makes sense for a local government — especially one that’s a small part of a larger area — to try and conduct a redistributive program, taxing richer people to provide subsidies of any sort to low income people,” Olsen said.

Olsen also voiced concerns over where the bond money would be specifically used. In the context of affordable and low-income housing, funds could be used for a range of initiatives, from providing housing vouchers for the private housing market to setting up tenants in public housing complexes, which are fully operated by governmental agencies.

In a 2017 research document on Charlottesville’s affordable housing policy, Olsen mentioned aggressive expansion of Section 8 homeownership through CRHA as a possible alternative solution for those in the City who are homeless or in need of affordable housing. Section 8 homeownership is a program giving low-income families opportunities to both rent and own houses through the use of vouchers.

“The evidence on the performance of low-income housing programs is unambiguous that it costs much less to provide equally good housing in equally desirable neighborhoods with tenant-based housing vouchers than in housing projects of any type,” Olsen wrote.

Duffield believes investing in affordable and low-income housing units not only improves quality of life for those who reside in those units, but also betters the community as a whole.

“Public housing is an investment that affords our community to be the community that we enjoy today, for everyone in the community and for our residents as well,” Duffield said.