Pediatrics Prof. Ronald B. Turner at the University Medical Center have conducted a preliminary study investigating the effects of DuPont Probiotic in an ongoing University common cold study. Initial results indicate a correlation between the bacterial makeup of the nose and the severity of common cold symptoms.

This first study began as an investigation into several scientific papers from China and Australia suggesting that ingesting a probiotic could modify the inflammatory response — the way the body responds to disease or injury — which contributes to the sickness of the patient. DuPont became interested in this finding and contacted Turner to research it.

“The question we asked was, does ingesting this probiotic impact the inflammatory response in your nose when you have a rhinovirus infection?” Turner said.

Rhinovirus is the virus that causes the common cold, and probiotics are live bacteria that improve gut health.

Clinical Research Coordinator Cheree Denby, in charge of recruiting participants and overseeing data collection, elaborated on the experiment’s design. University research nurses screen student volunteers via blood draws, determining the kind of antibodies — protein produced to counteract foreign bacteria, viruses or other agents — that are present in each student.

Once determined to have no antibody for the virus of interest, or other antibodies indicating that the participant is already infected with a different virus, each participant was randomly assigned to take a probiotic or placebo for 28 days.

Participants were then exposed to rhinovirus, and researchers made daily measurements of the type of symptoms exhibited.

Turner said the study was not entirely conclusive. They saw some effect on the host’s response to the virus. Specifically, the team discovered that one part of the inflammatory response in the nose seemed to be impacted by taking the probiotic. No other inflammatory markers were affected.

However, when it came to measurable symptoms, Turner said that the probiotic did not impact whether or not someone got infected with the virus.

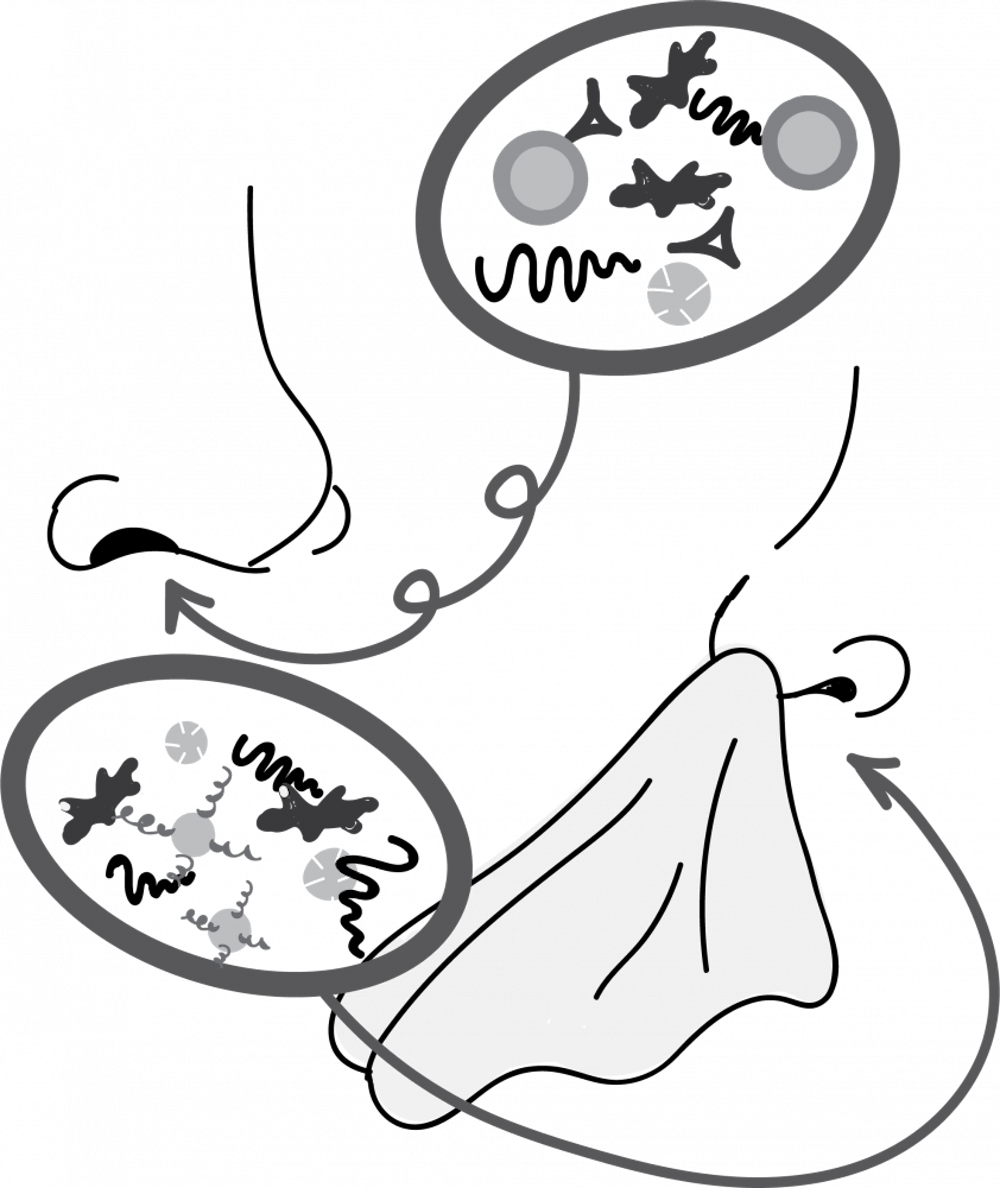

Researchers also collected samples of nasal microbiomes — bacterial ecosystems in the nose — and discovered a different relationship between the bacteria types in one’s nose and the severity of cold symptoms.

Turner said that volunteers tended to fall into one of six kinds of nasal bacteria patterns. One species of bacteria, Staphylococcus, appeared to have a greater impact on how participants responded to rhinovirus than others.

“We found that those who had a pattern associated with a predominance of Staphylococcus, had more symptoms … than those who had associations with other patterns,” Turner said. “So the types of bacteria you had in your nose at the beginning of the study seemed to influence how you responded to the rhinovirus.”

Yet, he stressed that it is important to distinguish an association from causation.

“It’s possible that there’s some characteristic up your nose that makes you have Staphylococcus in your nose and also makes you have more severe rhinovirus symptoms,” Turner said.

From these findings, Turner and his team devised and completed a second study to answer some of these questions related to the biological mechanisms behind these phenomena. Ending last May, he and his team of researchers are currently analyzing the data collected from this study.

Essentially, the experimental design and kinds of studies regarding the nasal microbiome and probiotic effects remained the same for this second study. However, the question shifted from looking at inflammatory responses to seeing if and how the probiotic prevents common cold illness.

Additionally, the second study increased from approximately 150 to 300 participants, doubling in size. Turner said this would increase their confidence in the results.

With regards to the microbiome aspect of the study, Turner articulated the possibilities of a future study to determine why Staphylococcus in the nose impacted cold symptoms.

“One way you could [investigate this is] … to take a bunch of volunteers who have Staph in their nose, treat half of them to eradicate the Staph, then infect them with rhinovirus and see if the association holds up,” Turner said.

Denby said this research could have widespread, real-world potential. Turner and Denby agreed that this research has potential implications for the possibility of a rhinovirus vaccine.