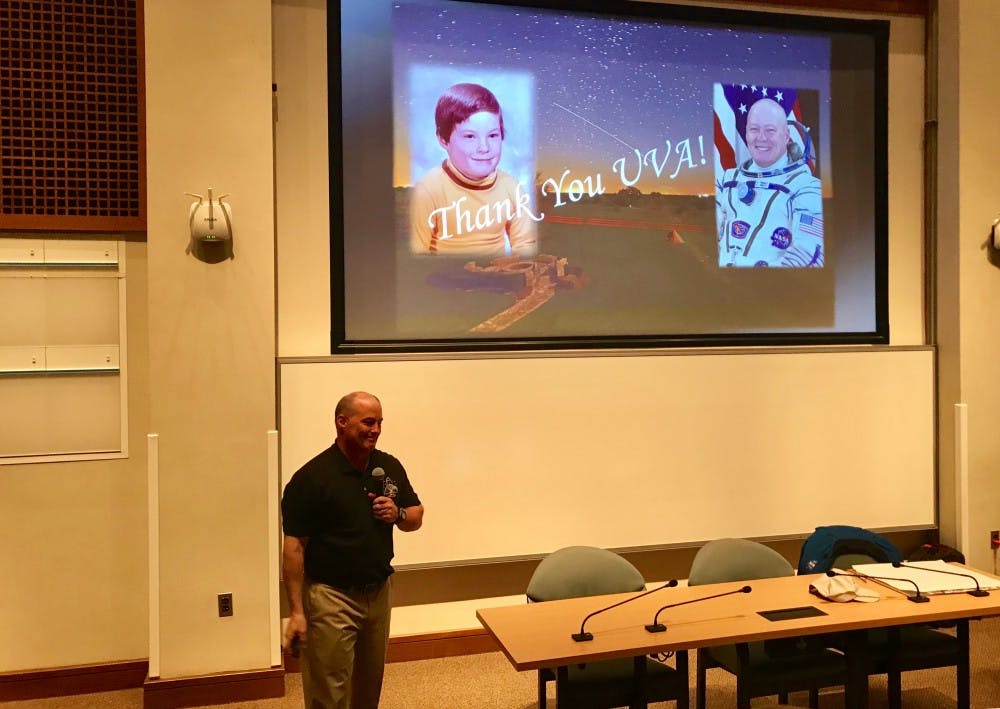

The Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics at the University’s Medical School hosted Captain Scott Tingle — a NASA astronaut who spent 168 days aboard the International Space Station — Monday afternoon.

Entitled “International Space Station Expeditions 54/55 Mission Overview,” the seminar was held in Pinn Hall. In the talk, Tingle discussed physical preparations on Earth, the launch, research onboard the International Space Station and returning to Earth.

Specifically, Tingle spoke about his experience as Flight Engineer for Expedition 54/55, which took place from Dec. 17, 2017 to June 3, 2018, where his mission was to conduct maintenance and experiments on the International Space Station.

Lukas Tamm, chair of the Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics, opened the event by briefly discussing Tingle’s educational background in mechanical engineering, experience in the U.S. Navy and his recent expedition in the International Space Station. Tamm and Tingle met at the Darden School of Business’ Executive Program in June 2015.

“We, his Darden classmates … all watched the critical episodes of his mission online and cheered him on as he completed them,” Tamm said. “It was wonderful camaraderie and we are therefore so glad to see ‘Maker’ [Tingle] back among us and tell us about his experiments and actually human physiology up in space.”

Tingle began by showing a video montage of Expedition 54/55. The footage included scenes such as of himself and two other crew members seated in a small cockpit wearing space suits, operating a space suit outside of the station, growing lettuce and playing instruments for outreach events.

“On station, again, it's an engineering marvel,” Tingle said. “We do operations, maintenance and science and living onboard.”

One of the systems that Tingle explained is the multi-constituent analyzer, which measures air quality. A common complaint among astronauts in space is headaches, and a possible contributor is the higher concentration of carbon dioxide inside the International Space Station when compared to the levels on Earth. Complaints about headaches decreased when a goal was established to keep carbon dioxide levels below 3 percent in the station.

Additionally, the were a wide range of experiments that took place during Expedition 54/55, including exploring antibiotic resistance in microgravity, plant growth in space, how human bone marrow is affected while in space and alternative fiber optic products.

One experiment conducted on the station used bioluminescent cells and spectrometers to measure how substances mix without gravity. By simulating those combinations on Earth, Tingle said, the effectiveness of certain medicines could potentially be deduced faster and at a lower cost than trials involving humans.

“We're also looking at polymers,” Tingle said. “On Earth, when you put the polymers together … they all tend to fall and get into a little bit of a pattern, but in space there's no gravity, so they just do what they want to do … You can really see how the bonds work and how the surface tension works and how the other drivers, minus gravity, really work.”

Conducting these experiments is challenging in a microgravity environment because the astronaut must simultaneously perform the research, hold themselves in place and prevent contamination. Also, particles and objects in the air can impact astronauts in the eye.

“You're in here in zero gravity, so it's not like you can plant your feet on the ground, right?” Tingle said. “You gotta get your feet up under something and hold yourself in while you're working like this and it can really get painful. There's lots of dust, there's lots of dirt, there's lots of debris floating around, we're always doing work.”

Experiments involving rodents also contribute to the dust and debris, as cages need to be cleaned out regularly.

“There's a huge amount of research that we get from live animal research up on space station,” Tingle said.

Much of the talk focused on the physiological changes a person experiences when in space. In zero-gravity, a lot of bodily fluid travels to the chest and the head, often causing the feeling of being upside down and sometimes leading to discomfort and vision impairment. The vertebrae in the spine decompress and bone density decreases, although Tingle said that that loss can be reduced through resistive exercise.

During the talk, Tingle projected charts displaying the changes in his bone density, fitness, weight and nutrition compared to the data of other astronauts before and after living on the International Space Station.

Tingle also volunteered as a subject in a study that examined human physiological changes caused by space travel. His brain activity was recorded in MRIs before and after the expedition, and through tests and activities while in orbit. His spine — as well as the spines of a few dozen other subjects — was mapped in MRIs before and after space travel. The information from this study on how the back relates to differences in pressure could be applied to help those on Earth limited to bed rest.

Astronauts are also exposed to a larger amount of radiation than an average person on Earth, making it an obstacle in space exploration.

“We're not seeing any negative results, or any trends in negative results, from being up here for six months,” Tingle said, “But [radiation] is our … biggest challenge for sending people to Mars.”

One attendee of the seminar was Stephanie McDonnell, a lab specialist at the University’s Cardiovascular Research Center. McDonnell said she found the talk interesting and informative.

“I’ve always wondered more about the medical and research aspects in space but just never really looked it up, so this was a cool opportunity to hear about it,” she said. “Being able to kind of hear about the challenges that they actually face like physically, like physiologically was really interesting.”