Each year, the Center for Biomedical Ethics and Humanities collaborates with the University’s School of Medicine to produce the Hayden-Farr Lecture in Epidemiology and Virology. The lecture honors the work of two distinguished University doctors — Medicine and Pathology professor Frederick Hayden and the late Barry Farr.

Jeffery Taubenberger — chief in the viral pathogenesis and evolution section in the laboratory of infectious diseases at the National Institutes of Health — gave this year’s lecture on Oct. 31 on the history of the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic and how it can be used to develop more effective preventative vaccines in the future.

Through his hour-long lecture — titled “On the Centenary of the 1918 Flu: Remembering the Past and Planning for the Future” — Taubenberger explained the history of influenza pandemics, the biology of how the virus works and evolves and how this information can be used to improve medicine.

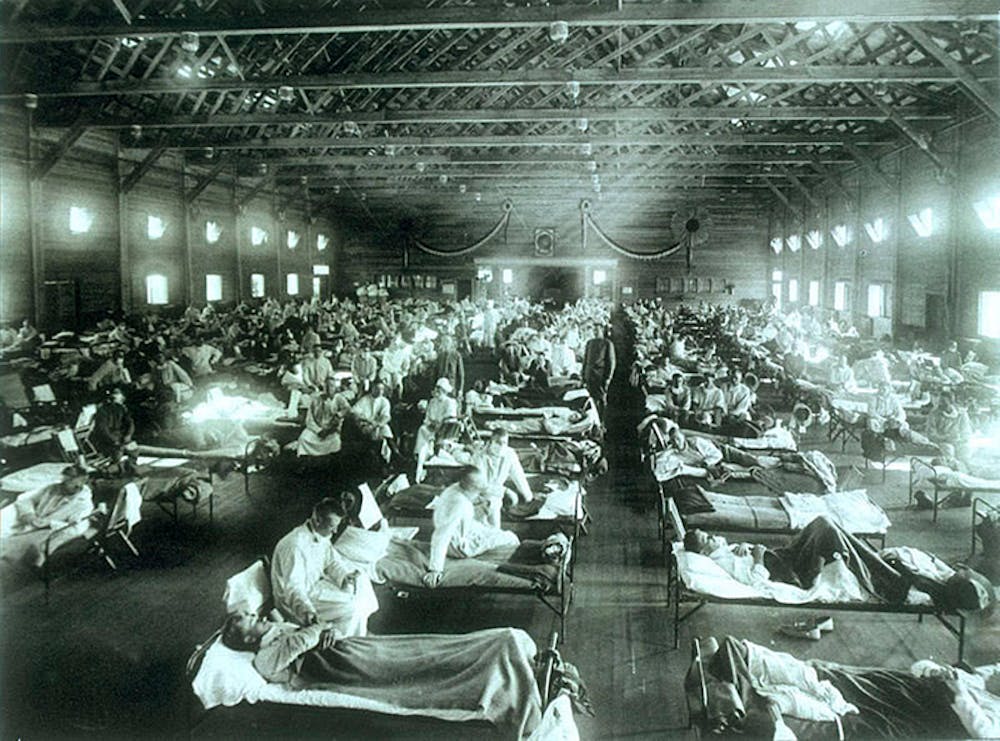

The pandemic of the 1918 flu, otherwise known as the Spanish flu outbreak, is estimated to have killed about 50 million people in a period of nearly nine months. The disease induced severe inflammatory responses in the body of those afflicted with it, and many cases at this time were marked by secondary infections of bacterial pneumonia that proved deadly if patients lived long enough to accrue them.

On top of the extraordinary scale of mortality, this flu pandemic was also abnormal in the types of people it impacted most. Taubenberger explained that usually, the influenza A virus has the greatest effects on the “extremes of life” — babies and the elderly — but this specific virus hit the human lifespan differently, with 28-year-olds being the group with the highest mortality rate on average.

Another aspect of the 1918 virus deemed important by Taubenberger was the property of antigenic drift, which stems from biological structure. The virus consisted of a single RNA strand and lacked a mechanism for proofreading, meaning that the genetic code of the virus could succumb to very frequent mutations, either positive or negative. This proclivity to change and mutation would most often be seen as a detrimental quality in biological molecules, but for a virus like the 1918 influenza, this was a key survival mechanism that has proven difficult to outsmart.

Mutations are what have allowed the influenza virus to evolve each year and form new biological disguises that are difficult to foresee and treat preventatively. Taubenberger called the 1918 virus “the mother of all pandemics,” explaining that genetically, all subsequent influenza pandemics shared many of the same proteins and structures as this virus.

The lecturer and a team of his colleagues made it their goal to understand the 1918 flu virus in hopes of applying it to all of the other more recent flu pandemics that have occurred and finding a better method to fight against the ever-changing virus more broadly. His team meticulously sequenced the genome of the virus in a ten-year effort.

“I had this crazy idea that we could perhaps use PCR-based approaches to find gene segments of the virus that caused the 1918 flu in autopsy tissues of people who died in the 1918 pandemic … and this project worked,” Taubenberger said.

After having achieved a successful “resurrection” of the unique 1918 influenza virus, Taubenberger and his team used this for what the doctor calls “model pathogenesis” in his laboratory. They utilized this reconstruction to understand what elements of the virus were most involved in the mutations of it. This was done through special types of studies called volunteer challenge studies.

“Healthy and very carefully screened volunteers are brought into the hospital and intentionally infected with circulating wild-type influenza viruses to study basic pathogenesis and immune correlates,” Taubenberger said. “We use this as a basis for Phase II studies, which are very efficient in terms of ability to look at efficacy of novel drugs, therapeutics and vaccines in small numbers of patients.”

Through these volunteer studies, the team found that one part of the virus that remained relatively constant throughout the constant evolution was the stalk of the hemagglutinin surface protein and inferred that vaccines that targeted this aspect of the virus might be more effective in preventing outbreaks, despite the unpredictability factor.

Taubenberger then described the application of these findings to the idea of a “universal vaccine” — a “broadly protective” approach to influenza inoculation that would account for a more vast and diverse spread of flu viruses so that evolution would not always be outrunning doctors and researchers.

“This could mean perhaps a vaccine that would give you better breadth of protection from seasonal viruses, so that maybe you don’t need to be vaccinated every year, maybe you only need to be vaccinated every five years or every 10 years,” Taubenberger said. “A broader one would be a vaccine that could actually be a pre-pandemic vaccine that no matter what bird or horse or swine flu that could get into people, of any subtype, that you could have immunity.”

A main idea delineated was that by using a non-infectious mixture of avian flu viruses hemagglutinin proteins, a wider scope of viruses would be accounted for, and an exact match of a specific year’s seasonal virus with the vaccine antigen would not be as necessary as it is now for efficacy. Taubenberger concluded his talk by summing up that his team of researchers hopes to conduct volunteer challenge studies by next year with new universal vaccine types they have been making.

After the lecture, members of the audience, whether current students at the School of Medicine or physicians themselves, praised Taubenberger and the thoughtful analysis he provided. Hayden, one of the namesakes of the lecture, was in attendance and described Taubenberger’s talk as a “tour-de-force and very much appreciated.”

Marcia Childress, director of Programs in Humanities at the Center for Biomedical Ethics and Humanities, closed the event by announcing that there will be no Medical Center Hour the week of Nov. 5 and aptly advised, “Don’t come next Wednesday — go get your flu shot instead.”