Since the recent emergence of the photograph on Gov. Ralph Northam’s (D-Va.) 1984 medical school yearbook page depicting a person in blackface and another dressed as a member of the Ku Klux Klan, the Virginian political sphere has been in turmoil. In the days that followed, not only has Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax been faced with allegations of sexual assault, but Attorney General Mark Herring (D-Va.) has announced that he also once dressed in blackface for a party — while he was a student at the University in 1980.

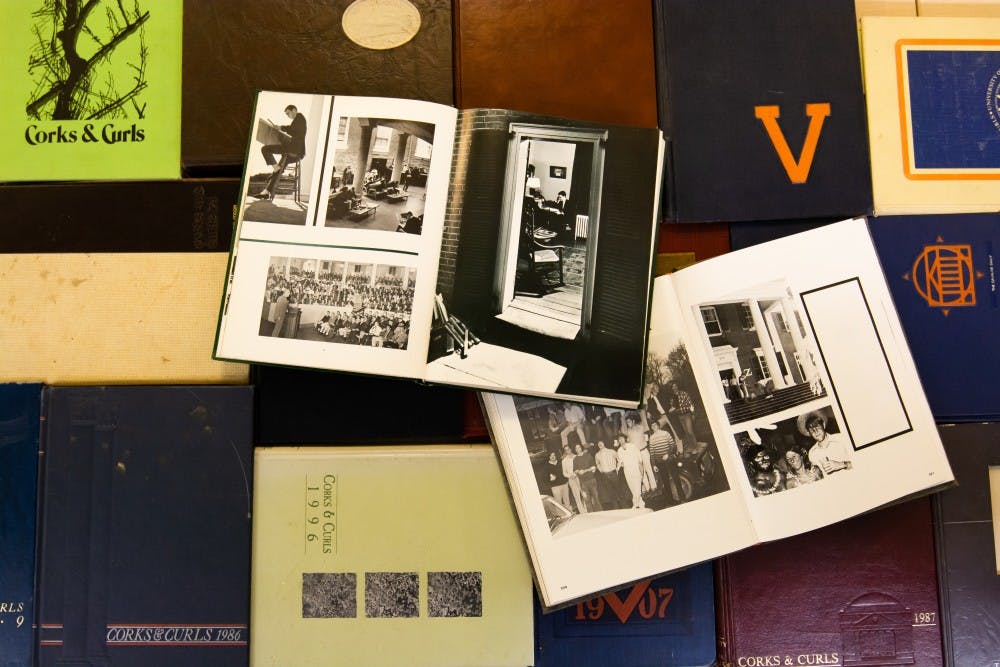

The resurfacing of these images has prompted investigations into the University’s own history of racist incidents and their lingering effects — and into the Southern collegiate culture in which individuals like Herring and his friends felt comfortable donning black face paint to impersonate a group of rappers. According to The Washington Post, the name of the University’s official yearbook — Corks & Curls — is actually a reference to blackface, “slang for the burned cork used to blacken faces and the curly Afro wigs that were signature costume pieces.”

The yearbook’s name has gone unchallenged for over a century, and John Edwin Mason, assoc. professor in the Corcoran Department of History, admitted part of that is due to a lack of general knowledge about the history of minstrelsy. Mason himself, who has examined the early editions of the yearbooks, was unaware of the meaning behind the phrase “Corks & Curls.”

“As much time as I’ve spent looking through Corks & Curls and as well aware as I am of the kind of racist imagery that appeared in it in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, I myself didn’t know about the connection with blackface minstrelsy in the name,” Mason said. “I think that’s really obscure.”

Until this weekend, the story of the yearbook’s namesake was available to read on the Corks & Curls website. According to their site, a student first coined the name back in 1888, and a contest was subsequently held to determine the best rationalization of the name. Allegedly, a student named Leander Fogg’s explanation that “cork” represents an “unprepared student who was called upon in class but who remained silent, like a corked-up bottle,” and “curl” meant “a student who performed well in class and who, when patted on his head by his professor, ‘curleth his tail for delight thereat,’” ultimately won out.

Ansley Gould, third-year Commerce student and editor-in-chief of Corks & Curls, said this account was written by a secondary source, not by the yearbook staff, so she took it off the site and replaced it with scans of the inaugural book’s preface which tells a similar story without the mention of a need for a “rationalization.”

“I don’t believe it was ever a rationalization,” Gould said. “I think that we represent — at least in this day and age — we represent ourselves with our name being what the students are, and we’ve never associated it with this minstrel slang.”

An independent, student-governed organization, Corks & Curls was published regularly from 1888 until 2008 when the lack of financial backing led to the publication going temporarily defunct, according to Jenifer Andrasko, president and CEO of the University Alumni Association.

Corks & Curls was revived during the 2014-2015 school year by funding from alumni donations and assistance from the Alumni Association, to “further the yearbook’s important journalistic and historical mission of capturing student life.”

“A group of students said, ‘We want to start a yearbook,’ and needed some support and needed space to have some storage, and they needed a mailing address,” said Andrasko.

Since its revitalization, students who work on the yearbook have been attempting to spread awareness of its existence on Grounds, and say they attempt to represent the student body in a positive and comprehensive way.

“It’s supposed to be a moment in time at U.Va, to me at least,” Gould said.

Like the current Corks & Curls staff, Andrasko said no one from the Alumni Association was aware of the double meaning behind the yearbook’s name until last week.

“The controversy over the name is brand new,” Andrasko said. “We’ve never heard before the theory put forward in the Washington Post … However, at the same time, we can see how some can read a double meaning in the name and the nonsensical nature of the explanation and that there’s not much historical support for that reasoning.”

Upon examination, it has become apparent that Corks & Curls — the publication whose mission is to encapsulate the University experience — contains controversial elements within its pages as well. In its earliest volumes, racist attitudes manifested themselves in cartoons, stories and poems. For example, in the 1907 edition, a poem entitled “Janitopor” employs racial slurs and illustrations to describe the black janitor tasked with cleaning the students’ rooms.

Mason said that examples like this are commonplace in the yearbooks of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“None of this is new,” Mason said. “Those of us who have been working on U.Va history over the last few years are very aware of how much racist imagery is in Corks & Curls. Sometimes it’s the little cartoons that accompany a fraternity or a club, or sometimes it’s the photographs. There’s a series of photographs of the Glee Club in blackface from earlier in the century, and it’s not surprising for all kinds of reasons.”

Mason continued that the pages of these early yearbooks served to perpetuate racial stereotypes and allowed white Americans to exude an air of superiority.

“It reflects a larger, American visual culture — a visual culture that grew out of white supremacy and reinforced white supremacy,” Mason said. “It’s a visual culture that allowed people to literally see African Americans as inferior, African Americans as docile, or African Americans as humorous or African Americans as vicious.”

Though many of these examples are found in the pre-Civil Rights era — before the University was integrated or even coeducational — others are not so distant. Volumes from the past few decades are peppered with instances of candid cultural appropriation, blackface and yellowface, most often within the context of costume parties and other social events. In the 1972 edition of the yearbook, separate scenes from fraternity parties show two students with dark paint smeared across their faces and upper bodies mingling with the other guests — all of whom pictured are white.

An image from the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity page of the 1972 edition of Corks & Curls depicts a student wearing blackface.

Occurrences of this nature extend into the next millennium. In Nov. 2002, the Kappa Alpha and Zeta Psi Fraternities threw a party where three students arrived in blackface. Kappa Alpha was suspended by both the Inter-Fraternity Council and its national headquarters immediately after the incident, though its national headquarters lifted their suspension over the University chapter two days later.

Some of the racist imagery found in the yearbooks does not seem to be in jest. In the 1971 volume, a photograph of what appears to be a staged lynching is displayed on the two-page spread allocated toward the Chi Psi fraternity. It depicts a group of armed individuals in dark, hooded robes surrounding a tree where a mannequin dangles by its neck from a rope, its face painted black. “You know I’m not black, but there’s a whole lot of times I wish’d I wasn’t white,” reads the Frank Zappa quote on the following page.

When The Cavalier Daily posted that specific image to Twitter Thursday evening, it was met with a multitude of reactions, ranging from shocked disgust to hollow dread. Mason’s response was a simple, two-word tweet — “My God.” He said this photograph’s proximity to the present particularly jarred him.

“You know, 1971 is comfortably within my lifetime,” Mason said. “I know people who were in school in 1971. 1971 is my history, and to see it in a period that feels, to me, so recent, I think is what surprised me.”

Fourth-year College student Komi Galli also reacted to The Cavalier Daily’s tweet Friday. “This week I picked up my cap and gown to celebrate graduation,” he wrote. Noting that the dark robes of the individuals in the photograph resembled graduation gowns, Galli asked how, as black student, he was supposed to feel about graduation now.

“When I saw the pictures, I just felt frustrated that it seems like it was something everyone was participating in,” Galli said. “And I guess it made me wonder, how much of this still goes on, behind closed doors? Just because, it doesn’t seem like it’s something that would have died out, because it wasn’t that long ago.”

Galli had heard of Corks & Curls before this incident, but he didn’t know that it was still an ongoing publication. He said that the name of the yearbook should definitely be changed, but there is a lot more that needs to be done at the University level to alleviate the consequences of this resurfaced history.

“I think one of the main things that needs to happen is that there needs to be a platform where students of color can just express their reactions to what is going on right now,” Galli said. “I feel like it’s been pretty overwhelming for a lot of students to the point where it seems like we don’t want to talk about it. It’s just another thing going on that’s a bit exhausting for a lot of students of color, to just wake up everyday and continue to go to school here and find out that there’s so much racism rooted at this University.”

Gould said that she had never examined volumes before the year 2000 prior to this past week, and was upset by the content of the yearbook’s older editions.

“Since this came out, obviously I’ve been looking back through some of the old ones,” Gould said. “But what we’re really trying to push is that is history and we know we can’t change it, and it’s something that’s disturbing to us as well. But we want to move forward and show that even in recent years we’ve been pushing for more diversity in the book because this is a book that’s supposed to represent who U.Va. is and our student body at the time.”

Gould added that she is currently in the process of attempting to change the yearbook’s name.

“I’ve been in touch with some people on the University level about changing the name and going about the best way to do that,” Gould said. “But because now it will forever be associated with this racially charged incident, we should change it, and we want to be able to represent the yearbook in the best way possible.”

University President Jim Ryan shared a statement Friday addressing the racist images from Corks & Curls editions that had been circulating on social media recently.

“Many of these photos are extremely offensive and painful to view,” the statement read. “But while the photos themselves are shocking, their existence is not.”

Ryan added that the work currently being done by The President’s Commission on the University in the Age of Segregation has been influential in acknowledging the University’s history with race. Members of this Commission, led by Asst. Dean and History Professor Kirt von Daacke, have been reviewing the University’s yearbooks and other publications since November 2018, as well as the meaning behind the name “Corks & Curls.”

Through its research, von Daacke said the Commission has found two other allusions to lynching in the yearbooks — one in 1914 of a cartoon image depicting two students in blackface being lynched and the other in 1959 depicting former University Dean B.F.D. Runk in blackface hanging with a rope around his neck from a tree. He said they have also found several references to blackface minstrelsy, yellowface and cultural appropriation — which begins to disappear in the mid-1980s.

“They are filled with this material from 1888 until the 1930s and it appears as cartoons, as photographs, as stories,” von Daacke said. “They spend a lot of time in student publications writing stories in imagined slave dialect, so it’s something that’s going on here in the classroom and at all times.”

Von Daacke added that many students — not just those in fraternities — participated in these activities during “Old South” and “plantation” themed parties, which were common among Southern schools.

“It’s part of the culture in Virginia and certainly apart of the culture at U.Va. — and I think this explains what we’ve been seeing in the yearbooks,” von Daacke said. “Corks and Curls would have been the common parlance to describe a minstrel performance that was done in blackface.”

He added that the University’s yearbook should change its name due to its connection to blackface minstrelsy.

“There's lots and lots of material that early on speaks to the use of corking and curling as a generic term at the University, but then also lots of concern about white supremacy and lost causes in student publications in written form from the 1860s on so it's part of who this University really is from the very early period,” von Daacke said.

According to von Daacke, the Commission is considering a plan to publish their findings online through an email to the University community to start a conversation about race relations. The findings would be sorted into themes — including eugenics, clan and racial violence and gender — with context and historical background from experts at the University.

Next fall, the Commission plans to host a series of public events throughout Charlottesville to present their findings.

Additionally, some believe that while addressing the University’s history through measures such as the Commission is an important step in the school’s road to recovery, the destructive effects of its wrongs need to be examined even more urgently.

“We know that we have to do more than acknowledge the past,” Mason said. “We have to do more than acknowledge the harm that this University has done to the city, to the region and to the state, and look for ways to repair that damage.”