The Honor Committee’s recently-released Bicentennial Report includes extensive demographic data analysis of the body’s sanction rate for students at the University since 1987 — including statistics which reveal a disproportionately high sanction rate for students of color, especially African and Asian American individuals.

While the report shows that the disparity for African American students has declined sharply in recent years, the sanction rate for Asian American students continues to outpace the group’s growth as portion of the student body.

Between 2012 and 2017, Asian American students comprised 27.2 percent of all reports, which is disproportionate to their representation in the University student population. As of 2018, they comprise 12 percent of the student population.

The Bicentennial Report was released to the public Feb. 11 and is a comprehensive historical and statistical review of the Honor System at the University compiled and analyzed by the Committee’s Assessment and Data Management Working Group.

The report is the largest internal review of Honor at the University, featuring data from a century of annual dismissals, three decades of data on all sanctions and six years of full data from reports and outcomes. Sanctions are those outcomes of cases in which a student is ultimately considered guilty — whether through an informed or conscientious retraction, leaving the University admitting guilt or through a guilty verdict handed down through an Honor trial.

Between 1987 and 2017, the demographic makeup of the University has changed dramatically, while the overall student population — both undergraduate and graduate — has increased from about 18,000 students in 1991 to more than 24,500 in 2018. Between 1990 and 2000, roughly 10 to 20 students were sanctioned each year.

Between 2001 and 2010 — excluding the dozens of students who were sanctioned in 2001 from a single mass-cheating case — about 20 to 30 students were sanctioned per year. Afterward, the sanction rate has remained largely stable, with some declines taking place in 2011 and 2016.

The African American student population at the University has gradually declined from nine percent in 1991 (1,698 students) to six percent in 2018 (1,542 students). However, the Asian American student population has doubled from 6 percent of University students in 1991 (1,109 students) to 12 percent in 2018 (2,877 students). Meanwhile, the white student population has gradually declined from just over 75 percent in 1991 (13,402 students) to about 65 percent in 2018 (14,168 students) of the total student body.

Since 1987, African American students at the University have consistently been subject to higher sanction rates than other student groups, although this disparity has declined significantly in recent years. The Cavalier Daily reported in 1988 that “29.7 percent of honor accusations are made against black students, a number which is disproportionately higher than the approximately eight percent of blacks attending the University.”

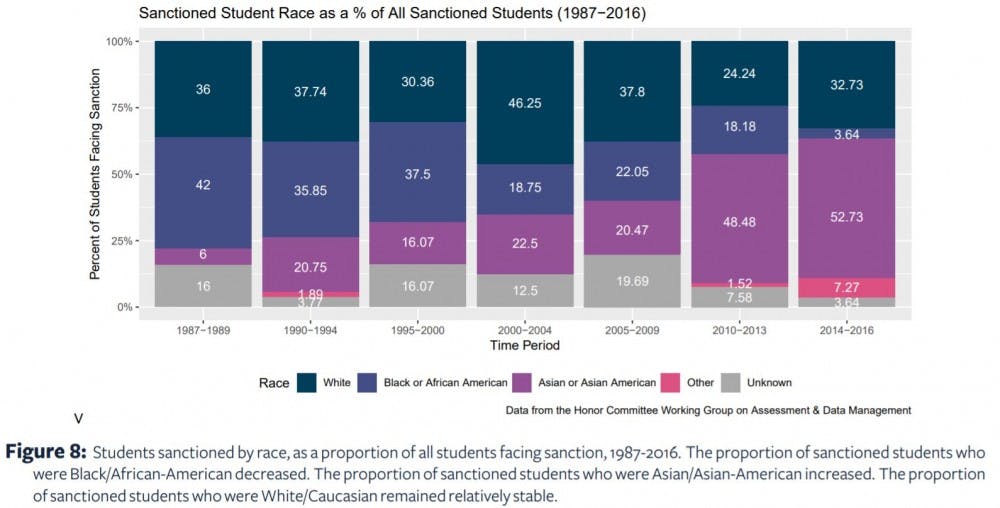

The white student population at the University has typically received between 30 and 40 percent of sanctions, although the rate was about 46 percent between 2000 and 2004.

Between 1987 and 1989, African Americans comprised 42 percent of sanctioned students, while the African American student population at the time was estimated to be around only nine percent. Between 1990 and 1994, African American students made up about 36 percent of sanctioned students but increased to 37.5 from 1995 to 2000. However, the sanction rate was nearly cut in half to just below 19 percent between 2000 and 2004, while it again increased slightly to about 22 percent between 2005 and 2009.

“Black students, especially student-athletes, often faced higher rates of reports than other groups of students,” according to the report. “As the Honor Committee made efforts to address the disparity, in 1999 the US Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights found that the Honor Committee did not violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”

According to the Department of Justice, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 “prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance.”

In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Charlotte McClintock, a fourth-year College student who oversaw much of the report’s development as Chair of the Assessment and Data Management Working Group, commented on the potential causes of the disproportionate sanctioning rates.

“We don’t have any direct evidence around why the the rate of African Americans who were sanctioned was so high, but we have a significant number of unknowns in our student-athlete data where the student-athlete information was available, it was often a student who was African American,” McClintock said. “So we think that cross section of black student athletes contributed to that significant disproportionality that we see from 1997 all the way through probably the year 2000.”

In recent years, the sanction rate for African American students has declined sharply to about 12 percent between 2010 and 2016. More specifically, the sanction rate was just above 18 percent between 2010 and 2013 and about 3.5 percent from 2014 to 2016.

In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Ory Streeter, Honor Committee chair and a fourth-year Medical student, said the decline in sanctioning for African American students relative to the rest of the student may in part be the result of increased sanctioning and reporting rates for Asian American students.

However, the report states that neither the disproportionately high sanction rate — nor its more recent decline — for African American students can be conclusively attributed to increased reporting of such students or an internal bias within Honor’s sanction process which led to the racial disparities due to a lack of data regarding the specific cases.

It does suggest that increased outreach to student athletes to provide more comprehensive academic resources may have partially contributed to the long term decline of sanctions as many of the African American students sanctioned in earlier years were athletes.

The report also notes that the racial sanctioning disparities may have been even worse than reported due to holes in data over time and unknown racial status for many past cases, with as many as 20 percent of cases in some years lacking racial identification data. The largest percent of students facing sanction with unknown racial status was during 2005-2009.

McClintock said these gaps in the data are largely the result of the Committee’s use of the Student Information System to keep track of demographic data, where it is sometimes unreported or otherwise unlisted. However, she added that the Committee hopes to transition towards to a student self-reporting system in the future to allow for more comprehensive data.

As the Asian American student population has gradually increased since 1991, the sanction rate for these students has significantly outpaced their presence at the University. Between 1987 and 1989, Asian American students made up six percent of sanctions, which was roughly proportional to the group’s student population at the time. However, the sanction rate increased to almost 21 percent between 1990 and 1994, despite only a slight increase in the Asian American student population.

Between 1995 and 2000, the sanction rate decreased to just over 16 percent but rebounded to about 21 percent from 2000 to 2009. However, the rate more than doubled to nearly 50 percent between 2010 and 2013 and increased to about 53 percent of all sanctions from 2014 to 2016.

Although the exact relationship is unclear, the sanction rate for students of international status also increased steadily from about 13 percent between 1990 and 1994 to roughly 21 percent between 2005 and 2009. However, that figure nearly doubled to almost 40 percent between 2010 and 2013, followed by a slight increase to 42 percent from 2014 to 2016. The population of international status students at the University has doubled from four percent in 1991 to eight percent in 2018.

McClintock said that even when holding other demographic factors constant — such as race, gender, student athlete status, student year and reporter type — international students are 18 percent more likely to face a sanction than other students after being reported. More specifically, McClintock said international students are statistically far more likely to claim an Informed Retraction than domestic students, thus contributing to the group’s disproportionately high sanction rate.

The IR allows a student who has been reported to the Honor Committee for an alleged Act of Lying, Cheating or Stealing to take responsibility both by admitting such Offense to all affected parties and by taking a full two-semester Honor Leave of Absence from the University community. A student may only file an IR during the 7-day period after the individual has been notified following the initial witness interview and before any hearing or trial process has begun.

According to an analysis in the report by Derrick Wang, a third-year College student and Honor’s Vice Chair for Community Relations, the top three countries of citizenship for international students at the University in fall 2017 were China, India and the Republic of Korea, respectively. During this time, graduate international students from China and India made up 41 percent of all international students, while Chinese international students comprised nearly five percent of the total student body.

While Wang writes that it is difficult to pinpoint the exact cause of the disproportionally high reporting and sanctioning rate for international students, he attributes the trend to a number of possible forces. More specifically, a lack of knowledge on the University’s Honor code due to linguistic, academic or cultural differences, academic and financial pressures stemming from high cultural expectations and an being in an unfamiliar environment as well as implicit bias in faculty.

“It is possible that some faculty members could have implicit biases that lead them to scrutinize international students more, leading to more reporting of international students,” Wang writes. “While it is unlikely that professors and faculty are explicitly targeting international students, they may implicitly suspect international students of cheating more often. This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy, since greater suspicion could lead professors to scrutinize international students work more closely, which could confirm the original bias.”

Wang adds that combating the problem will require a far more aggressive approach on behalf of Honor in terms of reaching out to and educating international students about the system. He suggests increased cooperation with minority student organizations on Grounds and the translation of Honor’s documents into a variety of languages. The Committee most recently announced the translation of its constitution and bylaws into Spanish in October.

“The vast majority of international students do not come from academic backgrounds with honor systems or honor codes,” Wang writes. “Many have never been in an environment where academic honor is heavily emphasized at all. Not only is the concept of a student-run honor system relatively new for international students, but for many this is their first in-depth exposure to the concepts of academic integrity, like formal definitions of plagiarism and academic fraud.”

Streeter also commented on the potential causes for these disparities, attributing them to “either bias on the half of the reporters or there’s some sort of underlying difference in the way international students engage largely academic material at the University.”

In addition to racial disparities, data from the period between 1989 and 2018 also shows wide gender gaps in the number of students who have been sanctioned with males always facing sanction than females. Since 1991, women have rapidly become the majority of the student body at the University.

The student population in 1991 was 52.5 percent males and 47.5 female, but by 1995, women became the majority of the student body with 51 percent representation. By 2005, the student population had become about 52 percent female, and peaked at 55 percent in 2010 before declining slightly to 54 percent in 2015.

Between 1990 and 2000, nearly 70 percent of all sanctioned students were male, although the sanction rate declined to an average of about 62 percent between 2000 and 2013, even as the female student population continued to climb. However, data for the period between 2014 and 2016 shows a significant narrowing in the sanctioning gender gap with men receiving about 49 percent of sanctions and women just over 47 percent.

Moving forward, Streeter said the Committee hopes to further engage the University community regarding the data uncovered in the report and set a precedent for future iterations of the Committee to do so as well.

“We're hoping that this is going to set a precedent for more transparent communication with the University community about the information that we do have,” Streeter said. “Because the point is we need to address the disparities that we see, we know that international students are overrepresented in our reports and are statistically more likely to face the sanction outcome within our system. If we sit on that data and we are hiding it, then that's not doing anybody any good.”

A complete copy of the report and additional information regarding Honor’s history, evolution and development is linked here.