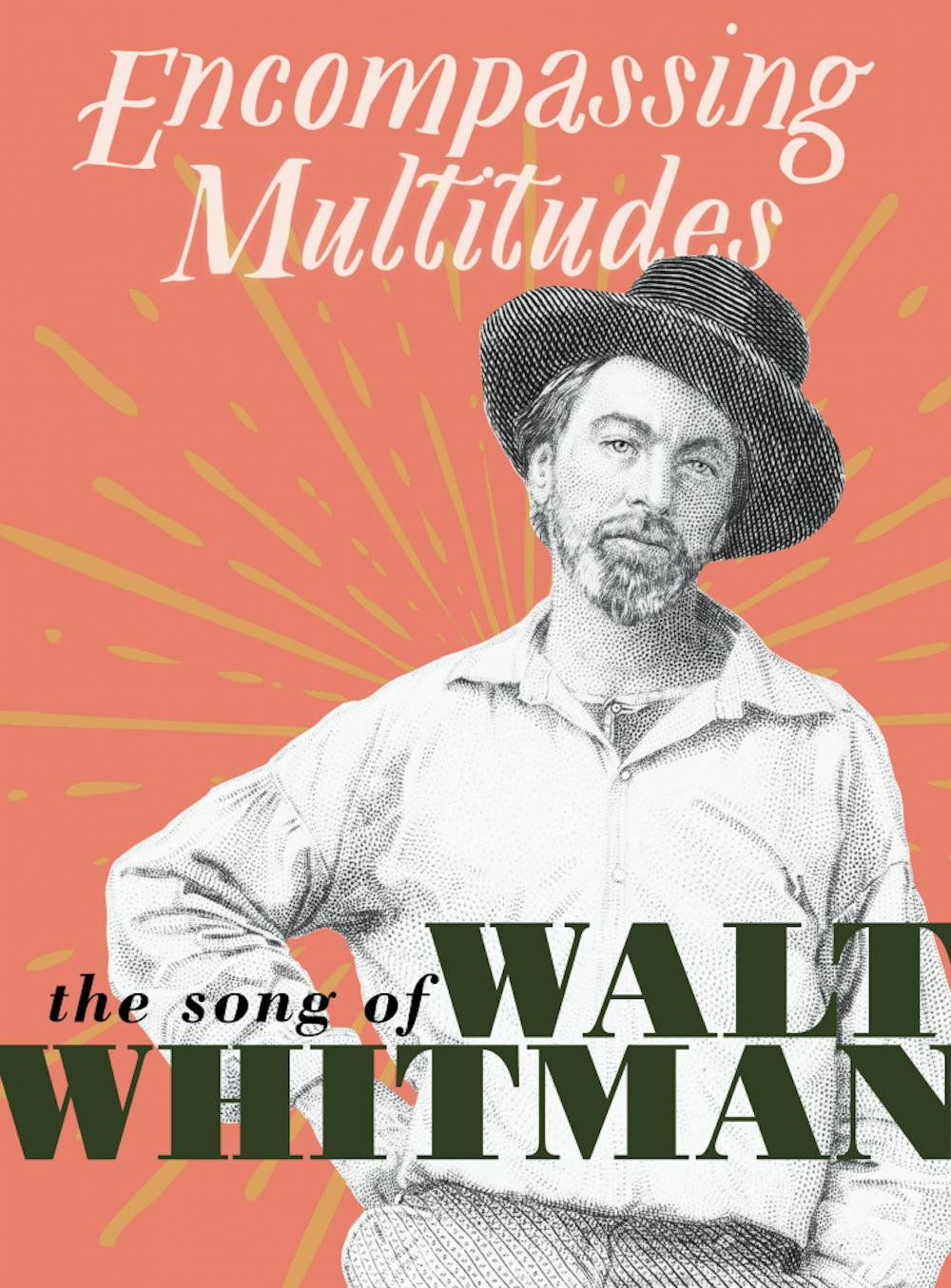

“Encompassing Multitudes: The Song of Walt Whitman,” a new exhibit located in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library — and curated by George Riser, alongside Robert C. Taylor Professor of English Steve Cushman, Director of Creative Writing Lisa Russ Spaar and Library Ambassador and former Wolfe Undergraduate docent Charlotte Hennessy — is designed with purpose. Upon entering the main room, viewers immediately notice the first display, an impressive poster filled with quoted early reactions to Whitman’s magnum opus “Leaves of Grass,” originally published in 1855. One side of the poster features positive reviews — while the other is, to say the least, a bit more critical.

“It is impossible ... to imagine how any man’s fancy could have conceived of such a mass of stupid filth, unless he were possessed of the soul of a sentimental donkey that had died of disappointed love,” one particularly rude — though creative — critic opined.

“If the ‘Leaves of Grass’ should come into anybody’s possession, our advice is to throw them instantly behind the fire,” another reader suggested, alongside a quote which labeled the poetry collection “intensely vulgar” and “absolutely beastly.”

Most of these quotes are anonymous and pale in comparison to the opposite side of the poster, where Ralph Waldo Emerson calls “Leaves of Grass” “a wonderful gift” and Ezra Pound dubs Whitman “America’s poet.” Still, the denunciation reads a little stronger than the praise, and attendees may wonder why such inflammatory quotes are included.

Maybe the reason lies in the exhibit’s’ main theme and title — “encompassing multitudes.” It’s a quote patched together from a couple of lines in “Song of Myself,” Whitman’s ode to the masses which instructs readers to appreciate themselves, even one’s “contradictions.” Maybe quoting the poet’s detractors is meant to highlight his own contradictions — to push back against the idea that “America’s poet” was always so universally loved.

Whatever the motive, the quotes are an undeniably sensational hook for an exhibit that’s otherwise old books behind glass. That’s not a criticism — as old books go, Special Collections has a seriously impressive Whitman collection, boasting 10 first editions of “Leaves of Grass.” This statistic was according to John Unsworth, Dean of Libraries and English professor who, along with several other English professors, led the opening reception of the exhibit Tuesday evening.

Of these 10, several were on display in “Encompassing Multitudes.” The 1855 versions started the chain of subsequent editions, culminating in the “deathbed” version of 1892. Along the way, “Leaves of Grass” transformed, increasing from 12 poems to 389. Each new edition incorporated some other aspect of Whitman’s life, whether his experiences in the Civil War or his mysterious “adhesiveness” — the poet’s term for “male-male love.” As his poetry collection grew, so did Whitman’s fame. By the time of his death in 1892, he was a nationally renowned writer — or a nationally reviled one, depending on which side of the poster is consulted.

The life cycle of Whitman’s literature is clearly intended to be the exhibit’s centerpiece and for good reason. None of the other exhibits containing artifacts from his time — whether the sparse “Other Publications” display or “After the War,” which details Whitman’s uneventful Reconstruction-era years — hold nearly as much interest as the magnificent metamorphoses of “Leaves of Grass.” In a “Civil War” case, the weathered thigh bone of a private whose name appears in Whitman’s papers is also inexplicably presented, but this bizarre inclusion feels like an out-of-place grab for attention among more engaging displays.

Aside from the cases of “Leaves of Grass,” the other highlights of “Encompassing Multitudes” are the exhibits which draw parallels from Whitman’s life and work to contemporary artists and citizens. A display titled “21st Century Heirs” grants Kendrick Lamar the title of “modern-day Walt Whitman” and lists the works of Claudia Rankine and the University’s own Prof. Stephen Cushman — also a featured speaker at the opening reception — as having created work heavily influenced by Whitman.

The center of the room contains several video screens displaying scenes from the documentary-in-progress “Whitman, Alabama.” A video project started by journalist and filmmaker Jennifer Crandall, it consists of a film crew convincing strangers from the title state to read stanzas from “Song of Myself.” Diversity abounds onscreen as the “Whitman” crew approaches everyone from 97-year-old Virginia Mae Schmitt to the eight preteens at a skate park who make up the Creative Mindz Dance Crew. If sometimes overly sentimental — the schmaltzy string music in the background of Schmitt’s video threatens to drown out what she’s trying to recite — it’s also an ambitious project which lends new significance to Whitman’s assertion, “I contain multitudes.”

The greatest strength of “Encompassing Multitudes” is that it recognizes and knows to capitalize on Whitman’s continued timeliness. For all the stuffy, long-dead poets whose ideas fail to fit into a modern context, his wisdom remains pleasantly relevant. “Song of Myself” is a 19th century self-love manifesto. The poems of queer desire found in Whitman’s sequence “Live Oak with Moss,” rather than be marred with self-loathing like the writing of his gay contemporary Oscar Wilde, overflow with longing and heartbreak — as sensual and moving as any straight love poem.

His work is technically humanist, bridging the gap between transcendentals and realists, but Whitman’s poetry fits more comfortably in the former category, alongside hippie forefathers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Whitman’s “barbaric yawp” is transcendent in the sense that it defies boundaries of time, as meaningful today as it was a century and a half ago.

On the far wall of the exhibit, a Whitman “reading nook” sits in the form of an orange, floral-print couch backed by green velvet curtains. The idea is that visitors, having viewed the other displays, will grab a volume from the bookshelf stocked with Whitman and Whitman-adjacent authors and devour the words of the man whose life they have just studied — or maybe they’ll just sit on the couch a few minutes to reflect, overwhelmed by Whitman’s multitudes and the sense of community they provoke.

“Every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you,” Whitman says in “Song of Myself.” “Encompassing Multitudes” has built itself around the same concept. Whether you’re a tween pop-and-locking at a Birmingham skate park, a woman just shy of 100 reclining in her easy chair or a student at the University of Virginia, Whitman is for all.

“Encompassing Multitudes: The Song of Walt Whitman” will be on display through July 27, 2019.