Statues are built to commemorate historical figures, but they often take on histories of their own.

Charlottesville’s monuments of Lewis, Clark and Sacagawea; Robert E. Lee; “Stonewall” Jackson; and George Rogers Clark were all funded in the early 1900s by Paul Goodloe McIntire, the same man who donated the McIntire School of Commerce, the School of Fine Arts, the Amphitheater and the Orthopedic wing of the University Hospital. A Charlottesville native, McIntire used the wealth he acquired in the Chicago Stock Exchange to contribute to the “City Beautiful Movement.” This movement was not particular to Charlottesville at the time, but was also popular in the early 1900s with other industrial tycoons such as John Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie.

Built in 1919, the well-known statue of explorers Merriwether Lewis and William Clark, along with their Native American guide, Sacagawea, was the first statue commemorating the two men on the East Coast. Currently located at the intersection of West Main Street and Ridge Street, it was once the centerpiece for a now paved over Midway Park. Their legendary journey holds particular significance to the Charlottesville community as Lewis was born in Charlottesville and our own Thomas Jefferson commissioned the expedition to find “the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce,” he said to Lewis.

Although the statue was praised at the time of its construction, in the past few decades community members have been critical of how Sacagawea is portrayed in the figure — seemingly crouching submissively behind the two men. Protests beginning in 2001 eventually led to the inclusion of a plaque in 2009 on the statue’s base, commemorating her significance to the voyage.

First-year Engineering student Bethany Gordon, who is partially of Native American ancestry, said she does not, however, see the monument as entirely negative.

“Though it might not be approached in the right way, there would be other things I would protest before I would protest that,” she said. “I wouldn’t support that view of history, but the fact that the statues are there helps us remember how people once thought. It’s better not to forget.”

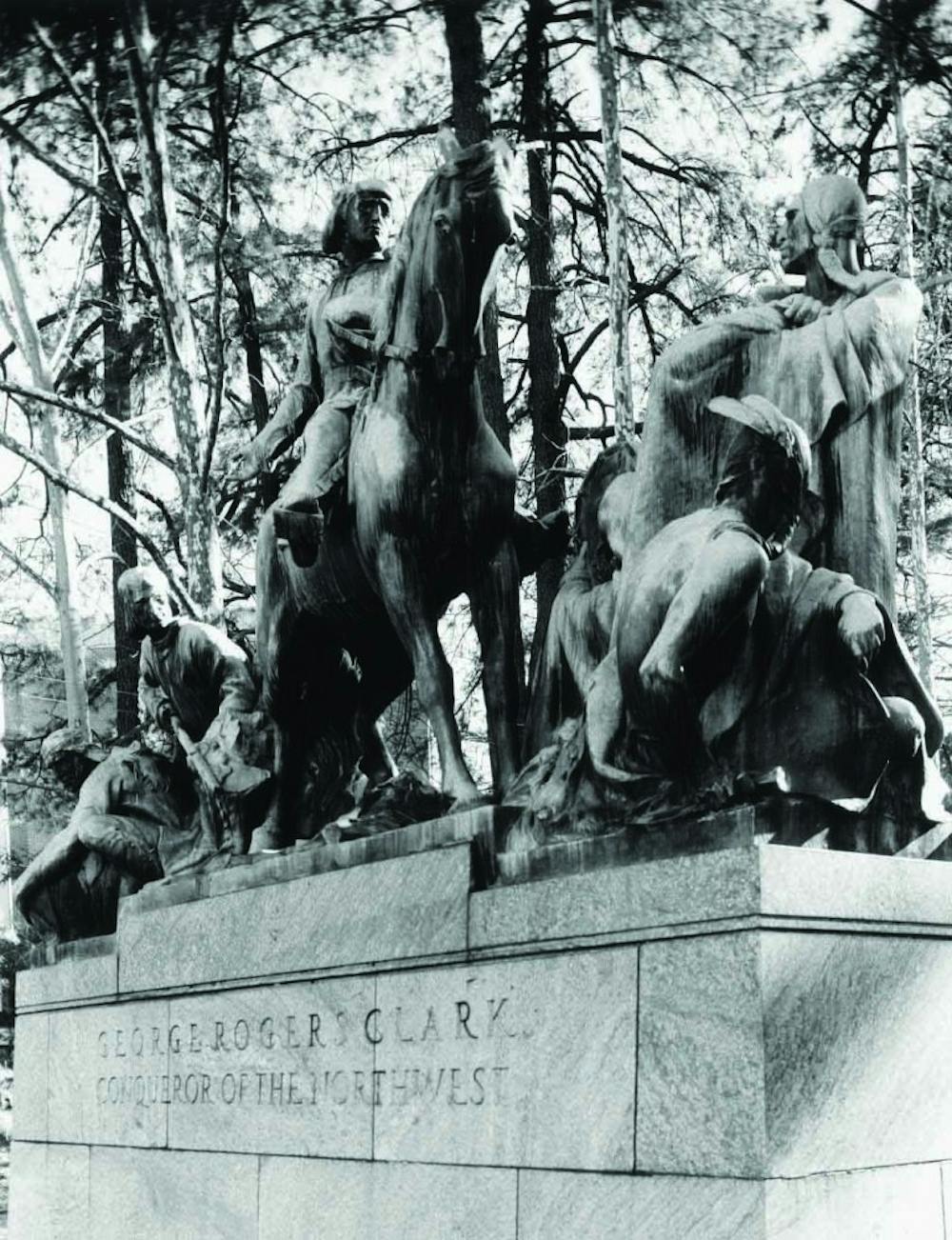

The statue of George Rogers Clark is the only one of the four located on Grounds, found at the intersection of Jefferson Park Avenue and Main Street. Brother of William Clark, George was born in Charlottesville before his family moved to the then-frontier, Caroline County, where William was born. He is considered the “Conqueror of the Old Northwest” because of his successful territorial acquisitions during the Revolutionary War.

The University Dispensary, where medical students gained clinical experience before the University Hospital was constructed, was torn down to make room for George Clark’s statue in 1919. The steps to the dispensary still remain along the sidewalk.

But two of the most controversial figures in the City are those of Confederate heroes, Robert E. Lee and Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson. The statue of Confederate commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee, found in Lee Park off of the Downtown Mall, was presented in 1924 at the same time as a Confederate reunion. Lee’s three-year-old great-granddaughter revealed the statue by removing a Confederate flag enshrouding it, and the first University president, Edwin Alderman, gave a speech of acceptance. Sculptor Henry Shrady worked on the design for 19 years but died while still making the model; Italian immigrant Leo Lentelli completed the statue.

Confederate general Stonewall Jackson is found in Jackson Park close to Lee Park. The statue was presented in 1924 during a celebration that McIntire explicitly wanted the Confederate Veterans, Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Daughters of the Confederacy to plan. During the presentation, school children sang and formed a living image of the Confederate flag, and Jackson’s great great-granddaughter unveiled the statue.

As suggested by celebrations held at the time, memorializing these two generals was welcomed in the 1920s by a number of Confederate sympathizers. Whether these figures should remain as prominent images in the Charlottesville community, however, has been the subject of more vocal controversy nearly a century later. Earlier this year, at the Virginia Festival of the Book, City Councilor Kristin Szakos and historian Edward Ayers, a former dean of the University of Virginia and current president of the University of Richmond, discussed the possibility of tearing down the statues. Others suggested erecting monuments of civil rights heroes to balance the Confederate presence.

“The statues were built by people involved in Confederate societies to commemorate heroes of Civil War and white supremacy,” American History Prof. Grace Hale said. “In the imagination of the builders, [Lee and Jackson] were heroes, but certainly not by others, even at this time, even by some whites,” she commented.

But rather than remove the controversial statues entirely, the community should present them as an opportunity to understand local historical identity, Hale said.

“It’s not the kind of public art we would put in the City today, but as a historian I would say there is something worth keeping there,” she said. “Creating interpretive materials around the statues that explain their history would be helpful, whether that be with a plaque or moving the statues to a different area.”

Despite the monuments’ surrounding controversies, for now, all four statues stand as reminders of the state and the City’s role in U.S. history.

This is the second feature in a series of four articles about Charlottesville history, commemorating its 250th anniversary this year.