Honor’s reach

The Honor Committee’s 2013 bylaws define the “community of trust” to mean “collectively, the students, faculty, administrators, and other members of the University of Virginia community.” But what are faculty members’ roles in this community?

Strictly speaking, faculty count as participants in the “community of trust” in that they can report students for violating honor code standards. But so can other students, and faculty’s role in Committee proceedings is anything but active.

“Faculty are simply referring a case [and] holding students to the system we chose,” Honor Chair Evan Behrle said.

And what about the Committee’s authority over the faculty themselves? “We have none,” Behrle, a fourth-year College student, said.

The Committee, which derives its authority from the Board of Visitors, in fact only has jurisdiction to convict students. Faculty may report students for violating the honor code, but they themselves are not held to it.

Behrle said any calls for including faculty in the existing student honor system would be largely impractical, noting it would create a system where the accused are no longer brought before a jury of their peers.

Faculty’s historical ties with honor

The honor code was actually not a part of Thomas Jefferson’s original design for the University — it came into existence in 1842, 16 years after Jefferson’s death.

The oft-quoted story that the honor code was created after a student murdered Law Prof. John Davis in 1840 was in fact just the final spark that ignited the animosity accrued during a four-year period of resentment between faculty and students.

“The first decade-and-a-half of U.Va. history was largely characterized by the unruly behavior of the arrogant students — students who almost exclusively came from wealthy, plantation-owning families,” said fourth-year College student Barrett Johnson, historian for the University Guide Service.

The continuing enmity between students and faculty, which originally resulted from bitterness left from a student-led riot in 1836, demanded a solution.

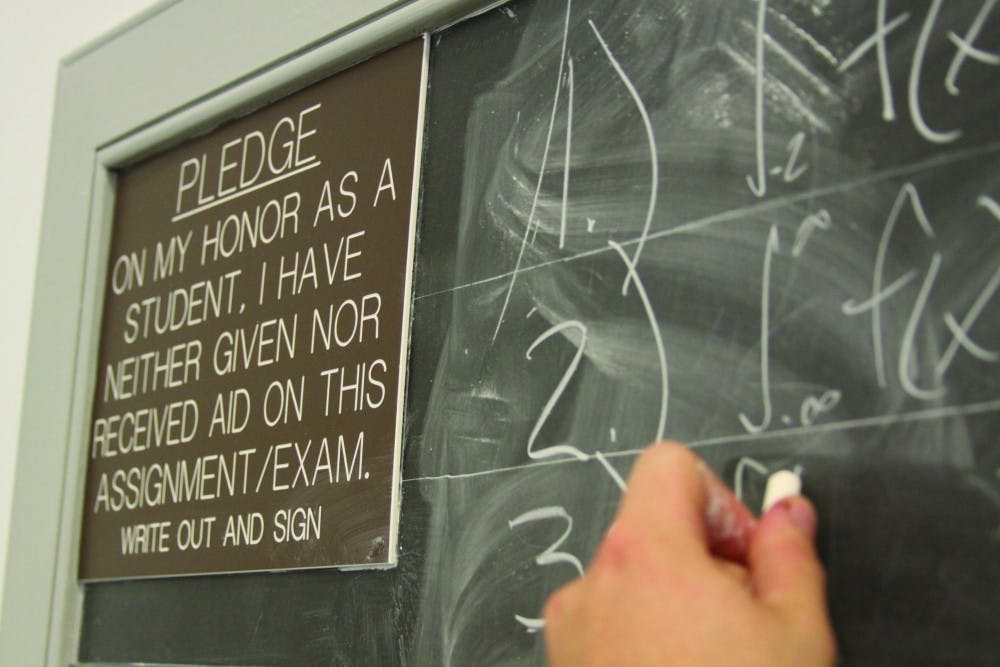

In 1842, Henry St. George Tucker, who served as Davis’s replacement, drew up the original honor pledge similar to the one students write on papers and exams today.

Ostensibly a gesture of goodwill to students, the proposal served to bring unruly students in line without alienating them. “This renewed appeal to the students’ honor was an effective move,” local historian Coy Barefoot said in an excerpt from “The University of Virginia honor code” in U.Va. Magazine. “Most of the well-to-do students from Virginia’s finest families thought of the pledge as a sign of their genteel status.”

“[From there] honor has evolved … from a pledge to a code to a system,” Barefoot said in an email.

Even in its nascency, then, the honor code has always been focused exclusively on student conduct.

An alternate system

According to a 2009 University policy on faculty discipline, the procedure for faculty who exhibit a “serious breach of professional ethics” involves notification of the accused, a meeting between the accused and the administrator who brought the accusation, and a “review” of the charges before a faculty panel, which recommends a decision to the provost, the final authority on the matter.

“It’s a combination between self-regulation and administrative [oversight],” English Prof. Jahan Ramazani said.

Religious Studies Prof. Bill Wilson said the overall number of infractions, much less suspensions or even dismissals, is low.

Infractions still exist among the faculty, though they often fall outside the spectrum of violations traditionally linked to honor. Both Ramazani and Wilson mentioned issues with sexual harassment of students and being intoxicated in class as some of the more common grounds for faculty dismissal. Honor infractions like academic plagiarism, they said, occur less frequently.

It is hard, if not impossible, however, to keep numbers on faculty disciplinary cases. “Unlike the Honor Committee or the [University Judiciary Committee], there is no central point of administrative contact for faculty disciplinary issues,” Maurie McInnis, vice provost for academic affairs, said in an email. “Many conduct concerns are resolved at a departmental or school level,” making tracking impossible.

There is overlap between the two systems of discipline, however, Ramazani said.

The faculty’s Code of Ethics contains language similar to the honor code, with faculty pledging not to “condone dishonesty in any form by anyone, including … theft, cheating, plagiarism or lying.” The code “encourage[s] and expect[s] reporting” of such offenses, just as the honor code asks students to report on those who lie, cheat or steal.

“There is an honor system insofar in that faculty can’t let cheating go,” Wilson said.

But when it comes to the student honor system, some faculty members are reluctant to fully engage.

“A lot of faculty have had concerns [about the honor code],” Ramazani said.

Wilson said the issue is even more pronounced. “It’s so dire … it really bothers people,” he said. “[Some] don’t want to be a part of it.”

The borders of between the faculty’s autonomy and the obligation to report are awkward at best. A memo, confirmed both by Wilson and Behrle, sent by the Dean of Arts and Sciences to faculty some 20 years ago left the reporting of student honor violations in a teacher’s class up to that teacher’s discretion.

“[There is] a cultural expectation that faculty report to the honor system, but no requirement,” Behrle said.

And although teachers are allowed to fail an infracting student on the assignment in question, the memo forbade faculty from failing the student in the class outright, unless failure of said assignment would naturally lead to failure of the class. This was done in part, Wilson said, to avoid faculty using grades as a form of “vengeance” against a student for cheating.

Some teachers have a rosier outlook on honor. “Having [the honor code] in the public mind so much is probably helpful for faculty as well to push us to do our best and to treat students well and honorably,” said David Edmunds, a new lecturer for interdisciplinary programs.