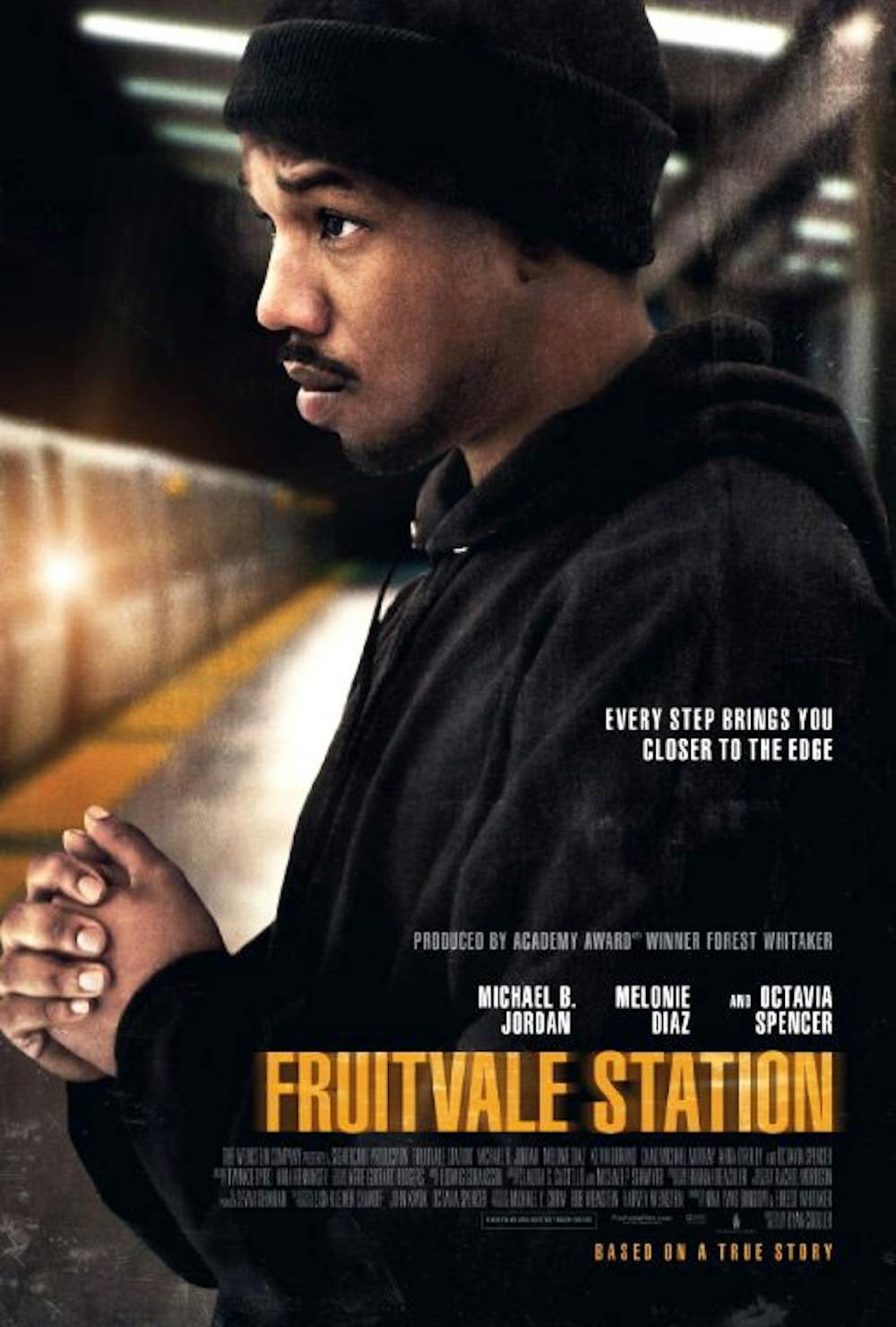

As part of the University’s commemoration of Black History Month, the University Program Council’s Cinematheque Committee partnered with the Office of African-American Affairs and the University chapter of the NAACP last weekend in presenting a double feature of “Fruitvale Station” and “12 Years a Slave.” The films focused on images of violence against African-Americans and the systematic marginalization of African-Americans in the United States in disturbing and poignant ways.

The event also featured a panel of students and faculty to discuss the films and how they connected to broader themes of racial tension and equality.

“One of our big goals is to be able to make this an annual event,” said second-year College Madeline Houck, a member of UPC. “Obviously Black History Month is a very important part of the year and of our culture, and we’d like to continue fostering these conversations. Cinematheque offers movies almost every weekend, but we rarely have conversations about them.”

Racial tensions still permeate modern culture, both nationally and at the University. The Trayvon Martin trial last summer ignited a heated national debate about the role of race in crimes, with many saying George Zimmerman’s actions against Martin were racially motivated, and the jury ultimately finding his actions justified. Tensions at the University are less blatant, but last month an anonymous individual scrawled “UVA Hates Blacks” on a sign outside Student Health.

“The movies emphasize how important it [is] to cover these types of things,” Houck said. “Unless you have publicity, you are never going to make progress in society.”

“Fruitvale Station” tells the true story of Oscar Grant (Michael B. Jordan), a young African-American father who was unarmed when he was shot by a Bay Area Rapid Transit police officer in 2009. Grant’s assailant was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter, rather than the original charge of second-degree murder or voluntary manslaughter, and was sentenced to two years in prison.

The film humanizes Grant, portraying his flaws as well as his virtues and providing perspective on a news story largely ignored by the mainstream media until three years later. The film’s music and tone appear sinister at first, forcing the audience to suspect the worst. But throughout the film, through a change in music and body language, the audience is confronted with their own incorrect judgments.

Michael Mason, a multicultural specialist Counseling and Psychological Services who served on the panel after both movie screenings, said the problem is not just with the police, but the result of “an ingrained psychological fear.”

“The only way we can deal with this is to become aware, and not just put this on the police,” Mason said. “All of us are racially profiling, socioeconomically profiling, stereotyping.”

“Fruitvale Station” grapples with the burden of the mistakes made that affect black men in particular, a narrative also mirrored in “12 Years a Slave.”

The critically-acclaimed Best Picture front-runner tells the horrifying yet hauntingly beautiful true story of Solomon Northup, a free black man from upstate New York during the pre-Civil War era who was abducted and sold into slavery.

The movie crafts a narrative about Solomon’s survival under ruthless slave master Edwin Epps (Michael Fassbender) and his effort to remain dignified as his liberty and humanity are stripped away from him. The movie succeeds in telling this heartbreaking story while managing to grasp at glimmers of hope and kindness that Solomon encounters throughout his journey.

“This film captures several things about slavery, [primarily] the system of brutal domination held up by incredible violence,” Assoc. History Prof. Kirt Von Daacke said. “I was really struck by … looking historically at these three systems — slavery, Jim Crow, and now the incarceral state. There is a 400-year-old system here. But we’re still wrestling with these issues.”

Like Grant and Martin, Northup never received adequate justice for the travesties he experienced. In the concluding credits, the audience learns that he brought his kidnappers to trial, but was unsuccessful in getting them convicted.

“The value of life for brown skin hasn’t changed,” Mason said. “[These movies are] a chance to reflect on advances we’ve made, and in some ways haven’t.”

During the panel discussion, an audience member challenged the panel to describe how to move the race conversation forward in a pseudo-post-racial society that has elected its first African-American president, but is still dealing with intolerance toward African-Americans. Mason pointed to the unique way movies can accommodate all racial groups in these discussions.

“We have to figure out a way that people can be emotionally prepared to think and learn,” Mason said. “And that’s a burden on all of us. … This movie gave us painful experience. But at the end we walk away saying after 12 years he got to hold his grandson. We needed that.”

Though the panel discussions only lasted for a few hours, they provided a glimpse of hope for the types of conversations the University can promote in the future. The event offered a safe space to share differing opinions, an aspect that is often lacking in racial dialogue.

“My experience is not the same ‘black’ that it means to my daughter,” Mason said. “And that’s not because she hasn’t been diligent about taking it in, but it’s because ‘black’ evolves. Each of us has a unique experience of blackness, or lightness, of American-ness.”