A recent psychology study conducted by University researchers found young children perceive their white peers experience higher levels of pain than their black peers in equal situations.

Arts & Sciences Graduate student Rebecca Dore, a doctoral candidate in developmental psychology, was the lead investigator of the study.

“We found was there was no evidence of the bias at age five, there was a weak bias at age seven and there was a reliable bias by age 10,” she said.

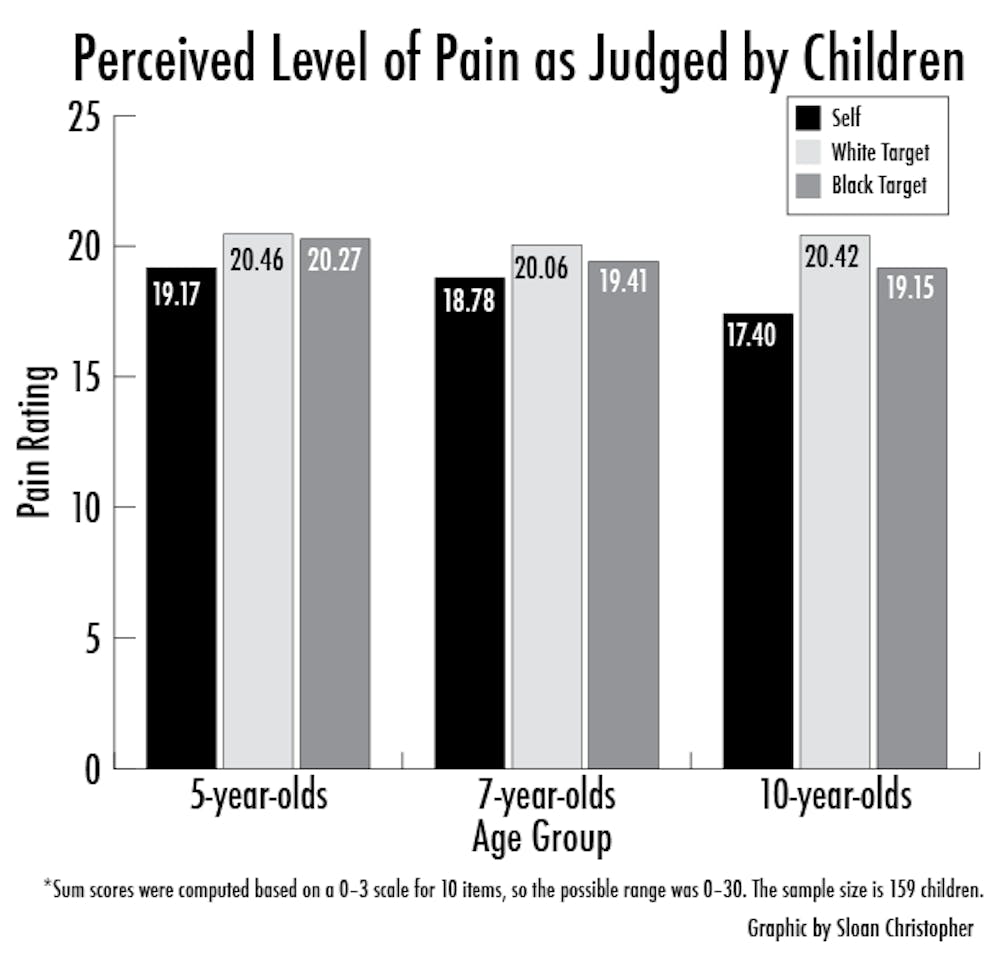

The study, published last Friday in the British Journal of Developmental Psychology, looked at a sample consisting mainly of white children from middle or upper-class backgrounds with highly educated parents. It compared groups of five, seven and 10-year-olds’ ratings of the pain they believed a black child and a white child would feel in a hypothetical “painful” situation. The children also rated the pain they believed they personally would feel in that same situation.

Combining the scores from all hypothetical situations, hypothetical “pain felt” was measured on a scale of 0, not at all painful, to 30, the most painful. At age five, there was scarce difference between the rated pains of black and white children but, by age 7, white children were rated on average as feeling 0.65 points more pain than black children. By age 10, white children were rated on average as feeling 1.27 points more pain than black children.

“It might be really important to start the interventions

early and talk to your children about race and racial issues

because they already are in the culture,

and showing some of these biases.”

The study built upon previous research showing a similar bias in adults. Arts & Sciences Graduate student Kelly Hoffman, one of Dore’s collaborators in the study, has studied this phenomenon across age groups.

“One reason people might perceive blacks feel less pain than whites is because they perceive them to have had a harder life,” Hoffman said. “There’s this notion of ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’”

Researchers believe the bias stems from the perception blacks are better equipped to deal with hardship, therefore feeling less pain than whites would in a similar situation.

According to Hoffman, this can lead to a host of negative consequences. Since blacks are perceived as feeling less pain than whites, for example, they can be undertreated by doctors in comparison to their white counterparts.

“We know that blacks receive less pain medication and are more likely to have surgical amputations from diabetes than whites,” Hoffman said. “Our work has shown that doctors do not even perceive [that blacks] feel as much pain in the first place.”

Dore believes this adult bias starts in childhood, increasing with age instead of remaining static.

“We are showing that this bias that can be really detrimental during adulthood is developing during the middle of childhood,” she said.

While specific causes of this progression of bias have not yet been determined, data suggests negative racial attitudes are not necessarily the cause, Dore says. Differences in participants’ racial preferences were calculated as part of the study and did not seem to greatly affect this bias.

“One reason people might perceive blacks feel

less pain than whites is because they

perceive them to have had a harder life,” ,

“There’s this notion of ‘what doesn’t kill you

makes you stronger.’”.

Dore suggests the bias may instead come implicitly, and hopes future research examining the association of hardship with different racial groups and the pain bias may answer this question.

Dore said she believes instigating dialogues about race and racial issues with younger groups of children may help mitigate these trends.

“By not talking about them, we might be making it worse,” Dore said. “It might be really important to start the interventions early and talk to your children about race and racial issues, because they already are in the culture and showing some of these biases.”