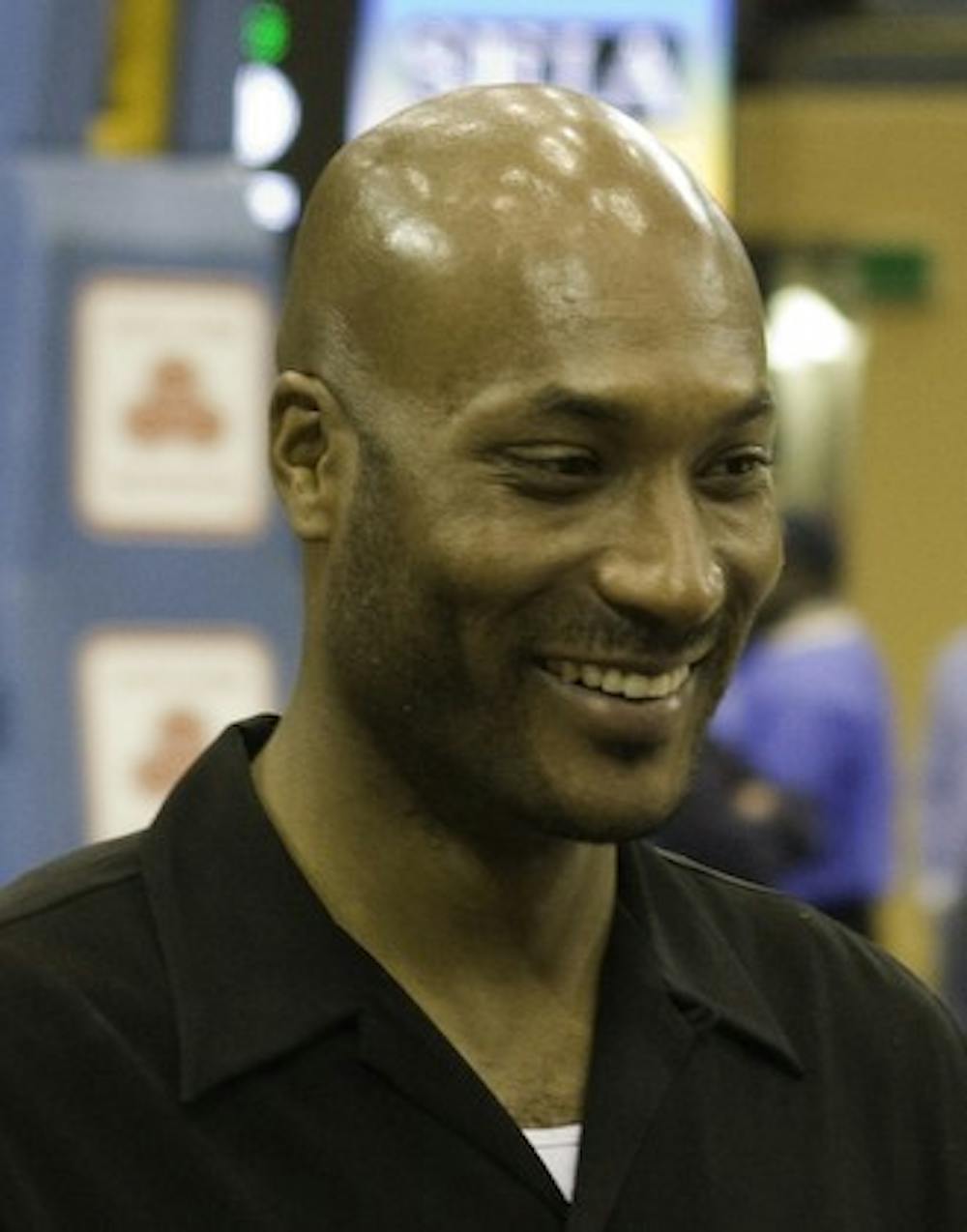

Nearly 20 years ago, Ed O’Bannon stood in the middle of the Kingdome in Seattle celebrating victory in one of more forgotten March Madness tournaments. A little more than month ago, O’Bannon stood outside of an Oakland courthouse with 19 other former athletes and celebrated what may amount to be one of the most influential court verdicts in sports history.

In her 99-page ruling, Judge Claudia Wilken categorically struck down the ideal of amateurism which the NCAA has employed in the last 30 years to defend its policy of refusing compensation for college athletes.

O’Bannon and his colleagues have now fought for the rights of college athletes for five years. They seek no financial gain, on a crusade to rectify what they feel are wrongs of the past. In many regards, they are right to do so.

Prior to the Aug. 8 ruling, the NCAA had essentially a permanent claim on the likenesses of athletes based on contractual agreements student-athletes sign prior to entering college. O’Bannon signed that agreement when he was 17 years old. The Student Athlete Statement dictates that by signing, all student-athletes allow the NCAA to use their names and pictures “to promote NCAA championships or other NCAA events, activities or programs.”

Nothing had ever been specified regarding the length of time the NCAA holds this right. Its lack of expiration has allowed the NCAA to profit off the work of student-athletes by licensing past games and continuing to profit through other royalties.

Wilken struck down the NCAA’s defense that compensating athletes in any form would tear down its core value of amateurism. Wilken cited the inconsistent application of the amateurism argument in the last few decades as the main reason for ruling in favor of O’Bannon. Many have applauded Wilken’s decision as a monumental ruling that will change the lives of the student-athletes for years to come.

In her ruling, Wilken stated that the NCAA must compensate student-athletes for the revenue generated off their likeness. The plaintiffs are pushing for the compensation to come in the form of trust funds that the athletes cannot touch until after they leave school. While O’Bannon’s efforts have resulted in great progress toward a more equitable relationship between the NCAA and student-athletes, the proposal to compensate student-athletes from funds derived directly from media and licensing revenues would have many unintended and destructive consequences for both the athletes and the NCAA.

Based on a third-party study by Stanford economics professor Roger Noll, O’Bannon and his colleagues are seeking a 50-50 split of media revenues and an one-third split on video games. Noll further calculated that in 2009-10 season, football and basketball players from the SEC and PAC-10 would be entitled to a total of $160 million in compensation based on fair economic principles and prices akin to those professional athletes and musicians enjoy. The totality of that compensation would be placed in trust fund for the athletes.

The problem with this proposed system is that this compensation would most likely have to be reported as income for the athletes on either the W-2 or Form 1099 as miscellaneous income. The IRS dictates that scholarships and fellowships are non-taxable as long as they are used to cover only tuition, room and textbooks, which this new revenue would not fall under, rendering it taxable. Unfortunately, even though the athlete would incur income taxes on this new source revenue, they do not have access to the money because it is placed in a trust fund.

According to Noll, in 2010, a football player at the University of Alabama would have been paid around $47,300 solely from media contracts. All $47,300 would likely be taxable, but the player would have no accessible cash with which to pay that amount of tax. O’Bannon’s efforts are valiant and there does need to be concerted effort to make the college-athletic model more equitable. But direct compensation of athletes from commercial revenue sources such as media rights and licensing is not a practical solution to the systemic problem.

Additionally, the competitive landscape of college athletics would forever be changed under a direct-compensation system. The gap between the haves and the have-nots would further widen. Programs such as the Texas, which have highly profitable TV contracts, would offer a significant financial incentive for athletes to join their programs regardless of their best interests as athletes. There are few reasonable ways to develop a compensation system for athletes without creating an upper echelon of five to 10 schools which will perpetually enjoy recruiting advantages.

Finally, as with any question regarding the allocation of resources in college athletics, the issue is further complicated by Title IX. It is not clear exactly how a direct compensation system would play into the provisions mandated by Title IX. In all likelihood, the female counterparts of each of the compensated sports would have to be compensated equally, even though they usually do not have the same underlying media and licensing revenue sources. Such a system would strain the athletic programs that are already struggling to stay competitive.

O’Bannon and his crusade has the right underlying goals, but the proposed solution will only exacerbate the inequality which currently exists in the NCAA.