“Exodus: Gods and Kings,” Ridley Scott’s new film about the well-known Old Testament book and the latest in Biblically-inspired epic films, has a bit of a misleading title.

The film, though enormous in scale, is not really about gods and kings at all. At its core, once the heavy CGI and convoluted side plots are pushed to the side, Scott’s film is about Moses’ interior psychological space. The main event of the film is the liberation of the Jews from Egypt, but what the film is really about is Moses’ psychodrama and his relationship with his adopted brother, Ramses II, his people and God. Don’t see this film for Scott’s overblown directing — see it for this almost-hidden narrative within.

Scott provides a secularized, psychologically-driven vision of the oft-repeated tale of Exodus. God makes a brief appearance as a burning bush, but comes to Moses mostly as a young boy with a British accent. Upon seeing this boy-God for the first time — a messenger, perhaps, just without the winged garb of an angel — I let out an audible scoff in the theater. God, as a small white British child? It seemed too silly to believe.

But Scott’s choice has interesting implications. Each time Moses converses with God, the camera flashes to an alternate perspective, showing that Moses is talking only to himself. Why is God a little boy in Moses’ mind? What does it mean when the other Hebrews can’t perceive God, but follow Moses regardless? Scott doesn’t take the time to answer these intriguing questions he sets up — instead showing a tendency to bombard the audience with too-long battle scenes and unnecessary CGI shots in almost Peter Jackson-like fashion.

Miracles, similarly, do not occur. The awe-inducing phenomena of the Book of Exodus are the result of natural causes in “Exodus.” The Red Sea doesn’t part — its current sweeps it away to one side of the basin. The Nile doesn’t turn red miraculously, but because of crocodile attacks on fishermen. And — perhaps most unprecedented of all — the Ten Commandments are inscribed by Moses’ own hand and not by God’s.

Biblically accurate? Decidedly not. In fact, some controversy has arisen around Scott’s choices. However, Scott may be the first filmmaker in recent years to attempt a Biblically-inspired film in this fashion, where the mighty and the miraculous have a root in the secular and psychological.

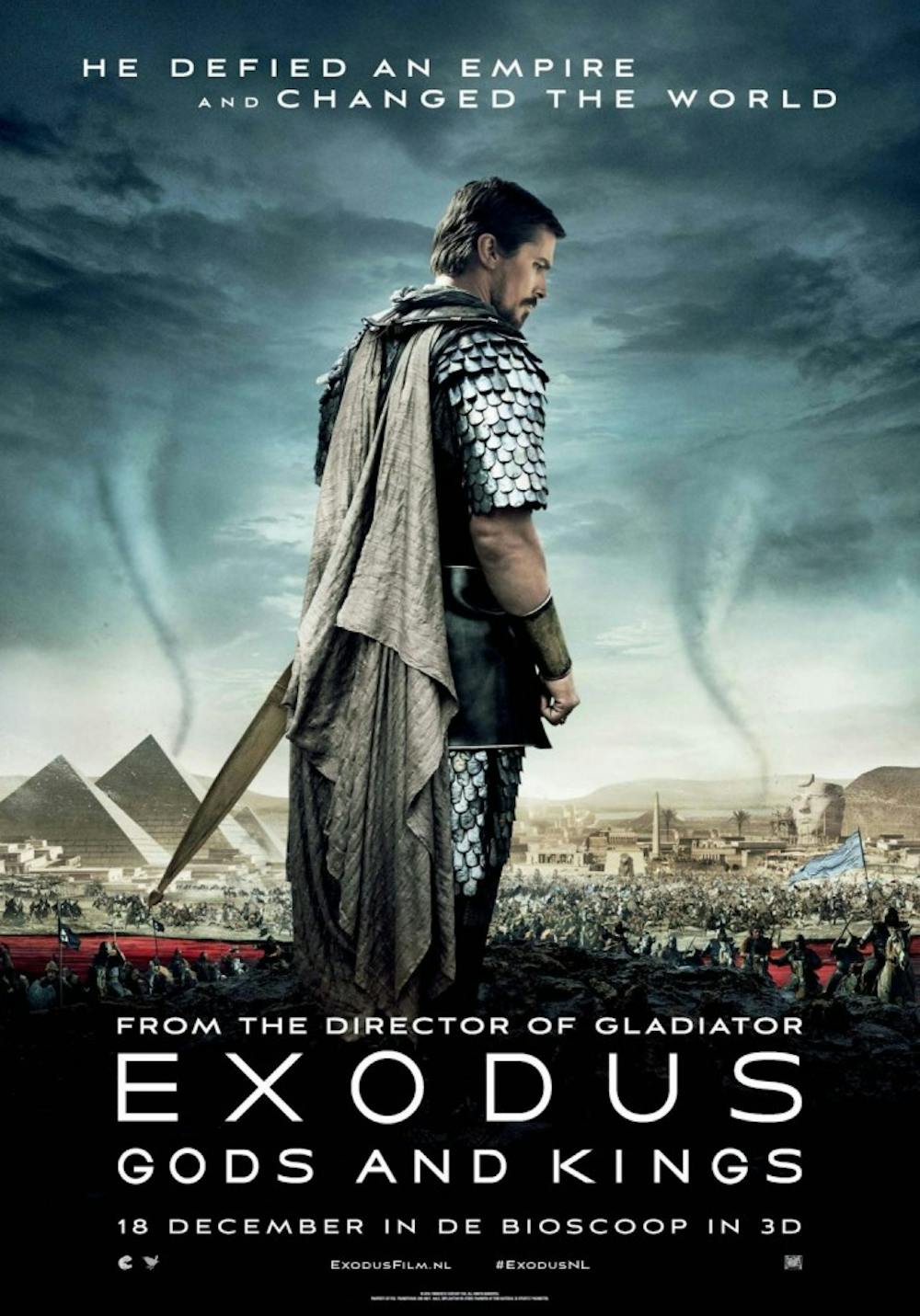

The rest of the film, sadly, is balderdash. The whiteness of the cast has been frequently criticized, but the overall poor quality of acting has not. It will forever confound me why Christian Bale was chosen to play Moses. Though he has brought gravitas to former roles, he lacks it here. Sigourney Weaver, playing Egyptian queen Tuya, is barely featured at all — begging the question why such a legendary actress even bothered (maybe there will be more in the director’s cut?). And the screenwriting is vacant and hollow, save one moment of polish in which Joel Edgerton delivers a Shakespeare-esqe soliloquy when refusing to free the Jewish slaves.

The film’s backbone is weak; the grand, elaborate production values would need a miracle to hide this fact.

If the film is worth seeing, it is for its unusual interpretation of a classic story. But if such matters don’t interest, don’t bother. The classic animation “The Prince of Egypt” manages to do more in 90 minutes than all of Scott’s 150.