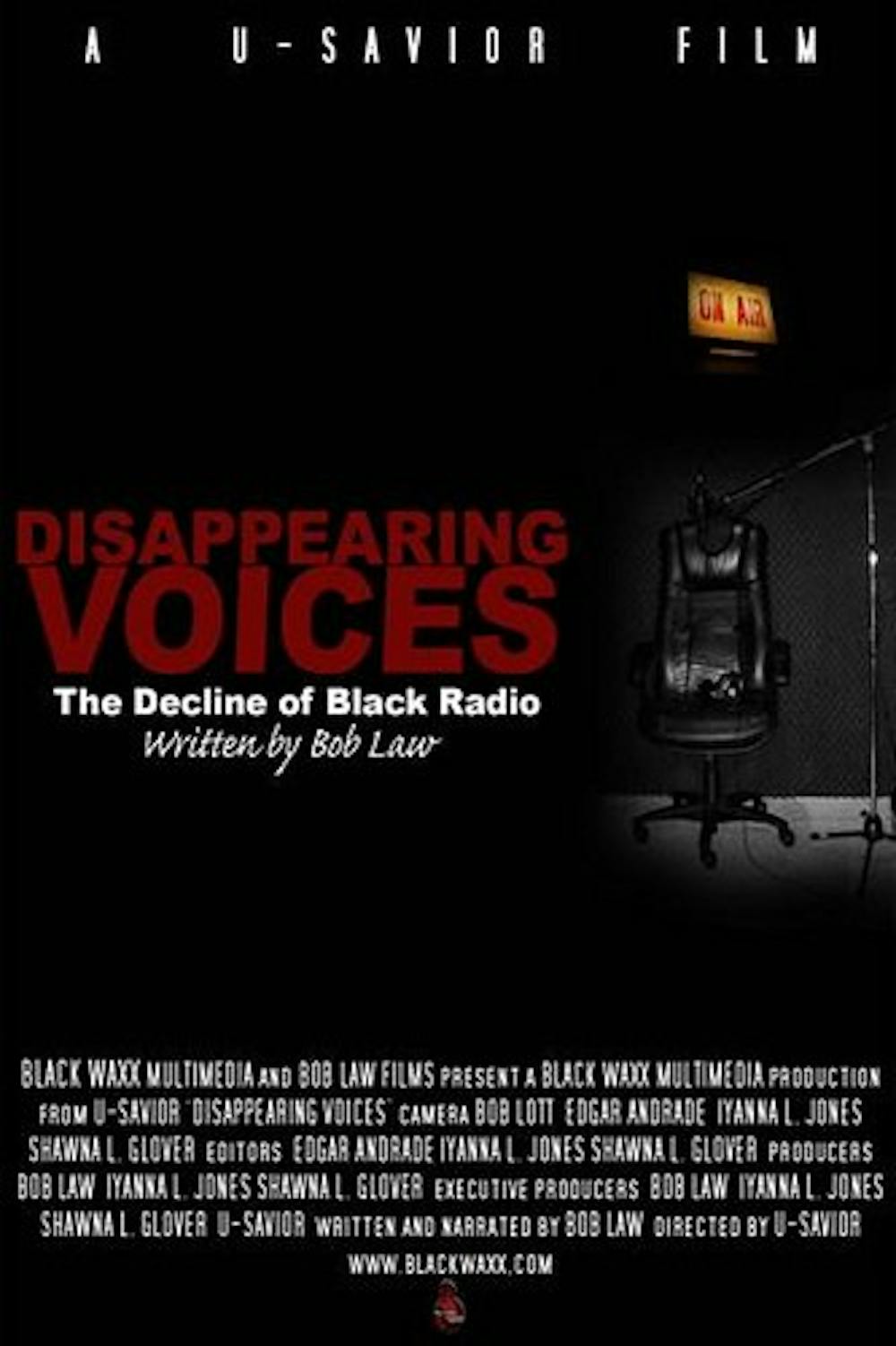

“You want prospects, not suspects,” Al Sharpton remembers hearing amongst a group of advertising agents discussing the pros and cons of investing money in black radio. “Hello America, we’re here,” viewers of the first black owned radio station, WERD, reminded audiences in Atlanta in 1949. These, amongst other racially-focused comments were made throughout the film “Disappearing Voices: The Decline of Black Radio” when it was screened this past week at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center.

The documentary discusses the history of black radio and the impact it had on a culture that craved diversity.

Presenting the audience with jarring statistics such as “13,000 stations exist in the United States but [black people] own 165 of them,” made a serious impact on the audience in attendance. Sharpton reminded us on-screen that black radio was once used to reach out to and bond the community. It was used in times of despair, anger and protest — sounds like something we, the black community, could use today.

The film also drew attention to research companies that claim to collect unbiased listener data, such as Nielsen Audio (formerly Arbitron). When those who worked on the documentary surveyed the streets of New York, all of the black people that were interviewed had either never been approached by Arbitron or had never heard even heard of the company.

My fellow viewers shook their heads in disbelief but it seemed that some members of the Charlottesville community were already aware of this. Andrea Douglas, the executive director of the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, mentioned she often finds herself trapped in a country music wasteland when crossing into Virginia. One viewer commented that Charlottesville does not have what he considers a black radio station: one in which the name on the license of the radio station is that of a black man or woman. For some, this was enlightening, but for others, it was a reminder that inequalities in the expression of black culture over radio waves is still a prevalent issue, not just nationally but locally, where we can do something about it.

The documentary did not just present an issue and leave it at that, it also offered solutions. Musicians such as Chuck D. of Public Enemy and M-1 of Dead Prez suggested not listening to a radio that does not want to hear our voice. Others reminded us that we own the airwaves and we can challenge licenses during renewal periods. The amount of agency we have as listeners and active citizens surprised many viewers. After watching the movie and discussing the issues presented, several people, who may have tuned in before, may consider turning the dial and raising their voice.