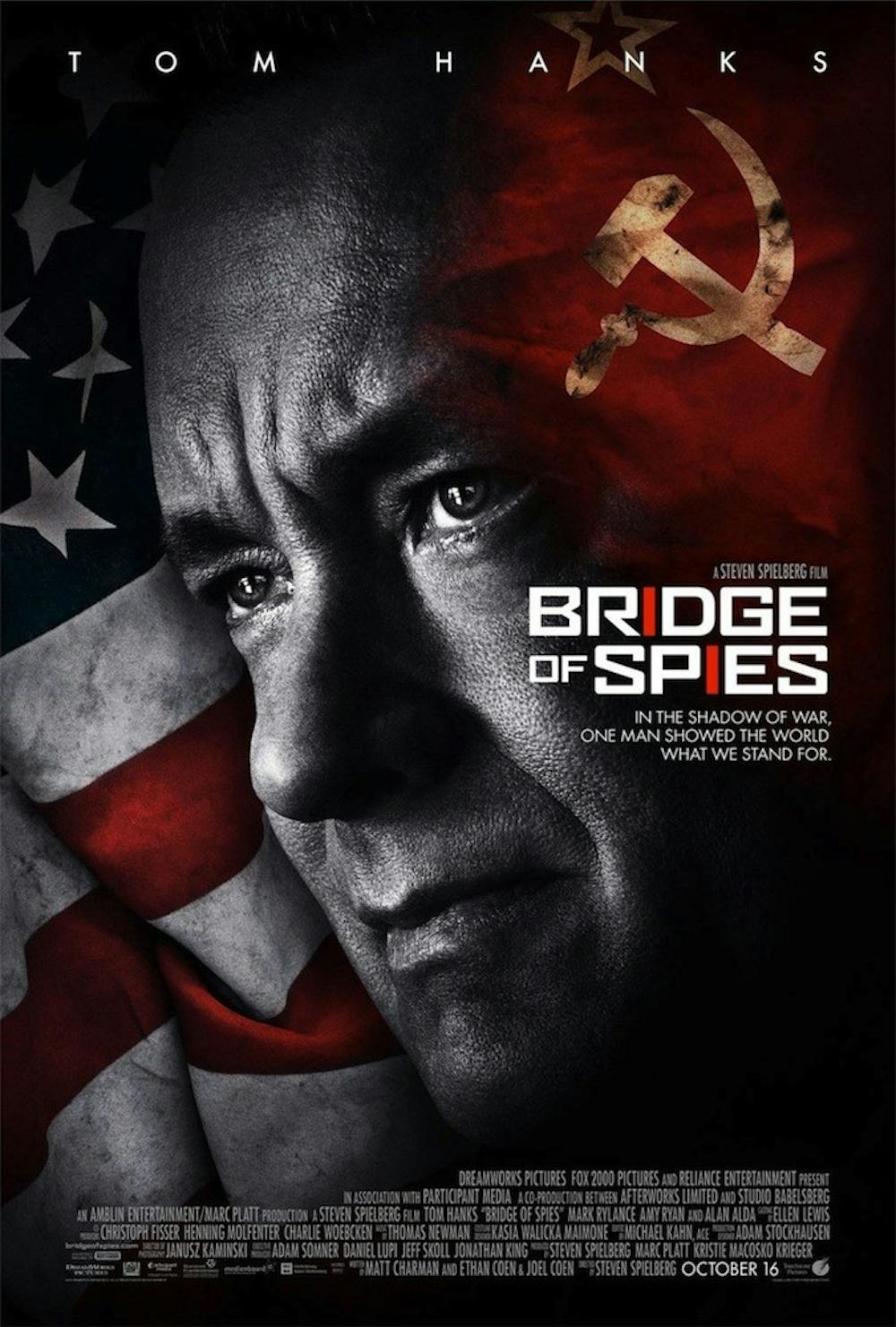

Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks have crafted a feel-good Cold War drama about American Idealism in a time of hysteria. The story focuses on insurance lawyer James Donovan, who was recruited to defend an accused Soviet spy in 1957 at the height of the Cold War.

Donovan is thrust into negotiating a high stakes prisoner swap when the Soviet Union captures an American U-2 pilot and East Germany detains an American student. The story is presented in a very classical, old-fashioned way that gives it a timeless feel, but this presentation may keep it from standing out beyond its status as a very well executed period thriller with a strong message. The movie’s trial and prisoner exchange segments feel very distinct, yet are definitely tied together by the same narrative arc.

Spielberg directs the movie with his usual flair and emotion. He frames the second half in East Berlin particularly well, creating great tension in Donovan’s negotiations while forcing the audience to piece together the dangerous landscape as Donovan does. However, Spielberg’s tendency towards the sentimental sometimes veers into territory that is too sappy and distracting. Nevertheless, this sentimental and black-and-white approach fits the clear moral compass of the story.

Tom Hanks effortlessly captures Donovan’s everyman appeal, as well as his strong morals and intelligence. Even as his country seems to turn against him for defending an enemy, he never sways in his sincere belief that even a foreign spy deserves a fair trial. His intuition pays off when Abel, the Soviet spy, becomes a bargaining chip and Donovan is sent to East Berlin to negotiate a swap. Hanks gets to play up Donovan’s appeal as an everyman hero in this section by insisting his desire to return home and get into bed instead of piecing together the competing Soviet and East German authorities with little CIA assistance. Through this, Hanks clearly demonstrates Donovan is engaged in these dangerous activities for no reason other than his belief that he is doing the right thing.

The rest of the ensemble does good work, especially Mark Rylance as the spy Rudolf Abel. He’s an enigmatic, low-key screen presence who nonetheless is always entertaining to watch. His overly calm nature is used to successful comedic effect at several moments. The American hostages are both given some background attention, but their characters are never fleshed out beyond broad strokes.

Ultimately, this story of valuing human rights and due process even in a time of political paranoia still rings true today. As Donovan suggests at one point in the movie, perhaps the best defense is to live up to these convictions even in cases where we may want to toss them aside.