Michael Bay is not a director known for subtlety. In fact, he may as well be called the “Grand Prince of Excess” — his filmography embodies the overindulgence of Big Hollywood.

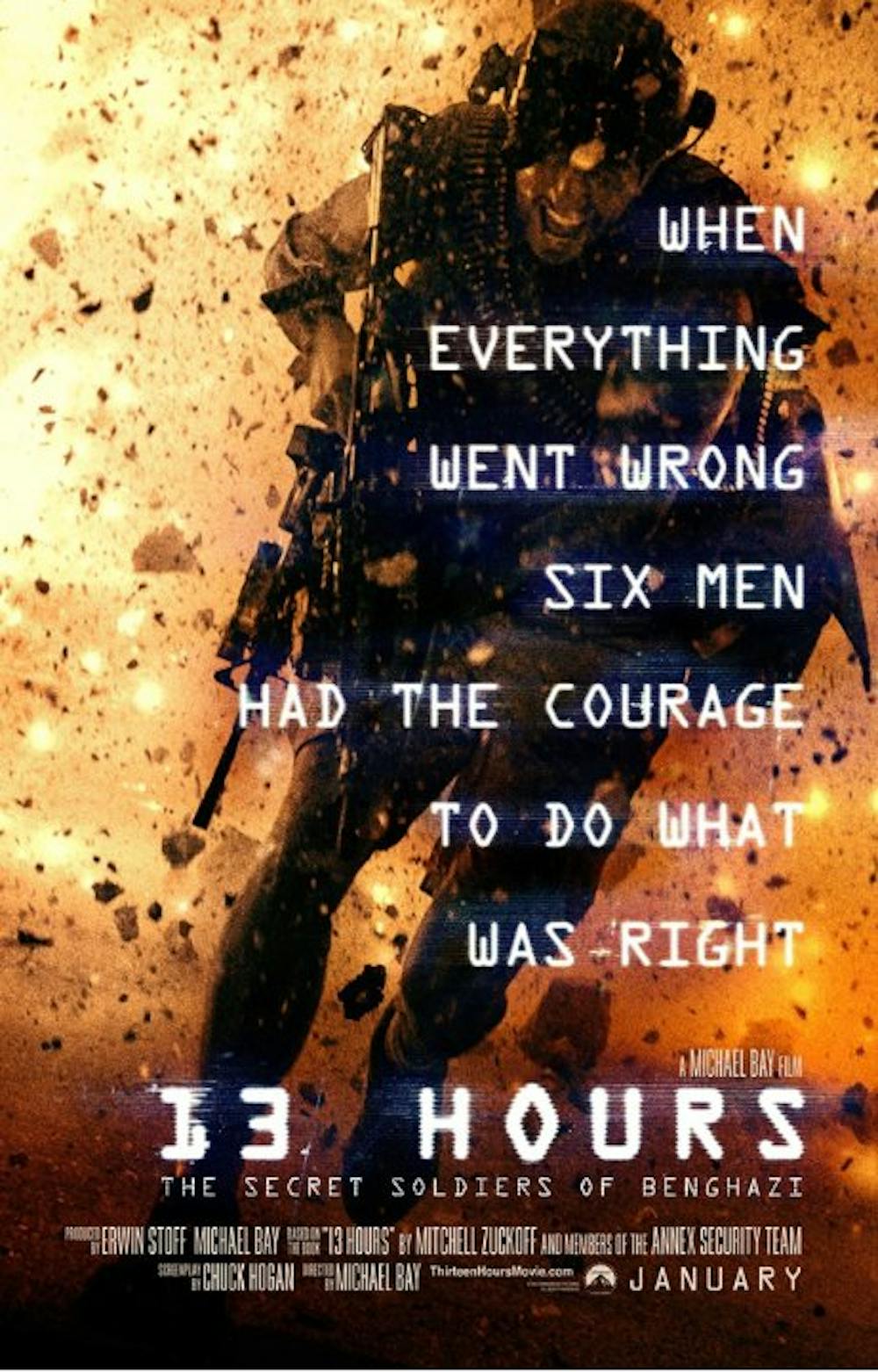

His latest work — “13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi” — recounts the 2012 attacks on a U.S. compound in Libya. It is more mature in both content and style than his previous efforts. In the film’s best moments, it even attains a genuine connection with the audience.

However, Bay’s signature quick-cutting, explosion-laden style fails to build suspense and oversimplifies the conflict it portrays, delivering neither the emotional impact nor the geopolitical context this true story of heroism deserves.

Nonetheless, “13 Hours” is a step forward for Bay. Instead of diving straight into the action, he attempts to explain the coming events with several intertitles — dialogue or narration presented on the screen — and tries his hand at meaningful exposition. One of the brightest moments of the film comes from Jack Silva (John Krasinski), who provides the most emotionally powerful moment of the film when he calls home to tell his wife he is well.

Yet, Bay’s lack of restraint precludes building any suspense, resulting in awkward pacing and a movie that seems like it should be over an hour before the credits roll.

Instead of his usual objectification of one-dimensional female characters, Bay opts for bizarrely sexualized images of Navy SEALs’ muscles amid out-of-place shots of them working out. A montage of soldiers video-chatting with their families back home is intended to elicit sympathy, but is marred by blatant product placement.

Visually, Bay sticks to his usual strategy of short-takes and gratuitous use of rack focus. When Bay likes something, there is no such thing as “too much.”

Even more troubling is the aggressively over-simplified American perspective advanced by the film. While it depicts the courage of American soldiers, it falls victim to the same trap as many other Hollywood war movies. “13 Hours” fails to explain U.S. relations with the foreign nation and the circumstances faced by innocent citizens. It glazes over the Arab Spring and Libyan Civil War and — most egregiously — hardly differentiates between combatants and civilians.

The film reduces a profoundly complex ethno-religious conflict into a shootout between a handful of Americans and many anonymous brown faces, and includes cringe-worthy uses of the phrase “bad guys” to describe potential insurgents. None of the central characters speak Arabic, and Arabic dialogue is not translated with subtitles throughout the film. This implies any language besides English is not worth understanding.

Even without these questionable directorial choices, it may have been too soon to make this film. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton testified before Congress about the Benghazi attacks last October. The issue is still very much alive on the presidential campaign trail for both Democrats and Republicans, and the film is now becoming politicized.

While it is undeniably admirable to honor the men who were lost, it is inappropriate to memorialize a battlefield before the dust has officially settled.