Since the early 1960s, U.S. policy has been created in reaction to public outrage over various issues affecting the environment. That sense of urgency is still present decades later, with economic gains now more than ever a decisive factor for policy implementation.

According to Carleton Ray, research professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences, the environmental movements in the 1960s focused on maintaining nature for the sake of nature itself.

The nature-for-itself framework prioritized the conservation of wildlife and habitats. A key event in this movement was the publishing of ecologist Rachel Carson’s 1962 novel “Silent Spring.” The book details the damaging effects of the pesticide DDT on animal life, vegetation and humans, bringing the use of toxic chemicals under greater scrutiny.

“When Rachel Carson wrote this book in the ‘60s, it inspired an environmental consciousness,” Ray said. “The first Earth Day [was in] 1971, and 20 million people in United States were marching. It was far bigger than any political thing you see today.”

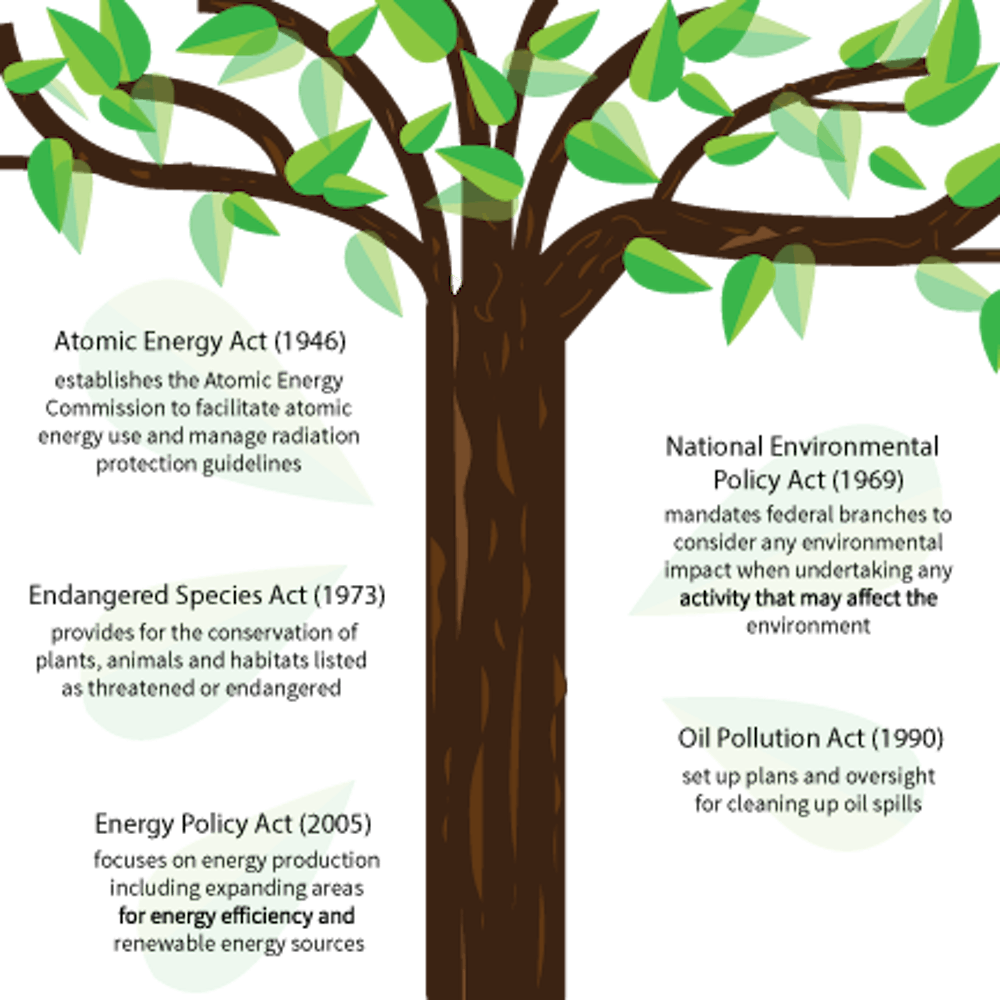

This interest in the well-being of the environment spearheaded a new sense of political responsibility from the public. In the 1970s, Congress enacted a succession of environmental acts due to an influx of activism.

“The legislation that was passed at the time between 1969 and about 1975 was absolutely astonishing,” Ray said. “The Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Endangered Species Act and the Fisheries Act — all of these acts came directly off of people power.”

Policies such as the 1970 Clean Air Act remain relevant today said Alex Wolz, fourth-year Commerce student and student co-chair of the Energy Working Group.

“The Clean Air Act ... there's language in it that allowed Obama to do the Clean Power Plan to limit emissions of coal-power power plants,” Wolz said.

Around the early 2000s, a new ideology concerning the environment took shape — nature for people. This belief focused on how ecosystems could benefit humans rather than simply how to limit human influence on the environment. Central to its definition is the creation of structures that will lead to the development of sustainable relationships between societies and the environment, such as through the creation of regulation that looks at how policies might affect the economy.

“The conservation movement became more and more concerned with nature for people, what services does nature provide for us,” Ray said. “There’s pollination for bees, there's a preservation of watersheds for our water, so it's all about us — the movement became more and more about us.”

According to Wolz, economic factors are largely responsible for the implementation of policies attacking issues such as climate change — one of the greatest environmental problems of our time. Policy makers often look for incentives-based initiatives such as cap-and-trade, which offers producers the chance to earn back money if they follow energy-efficient practices.

“Let’s say you're the avocado industry,” Wolz said. “The whole avocado industry can produce 100 metric tons of CO2, and you as a grower may get to produce 10. You have those 10 per year — you track them. The idea is that each year you ratchet it down a little bit more and a little bit more, gradually making the industry more and more efficient.”

Wolz said that providing monetary incentives to producers has been successful in the U.S. due to the nation’s more liberal economic system.

“We are very much a free-market based economy in terms of our socio-political thought,” Wolz said. “Cap-and-trade is a very popular free-market solution versus the government just saying, ‘You have to produce nine emissions now,’ which reaches the same end goal. But, it's just who's forcing you to do it — the market or the government.”

Another proposal offering fiscal entitlements is the recent carbon tax fronted by Conservative politicians in Congress. This policy would place a tax on any CO2 emissions produced by companies and individuals — making fossil fuels more expensive and thus encouraging a reduction in usage.

However, Environmental Sciences Prof. Vivian Thomson believes the carbon tax will not be implemented any time soon.

Recently, President Donald Trump’s administration has begun repealing environmental regulations implemented under former President Barack Obama’s administration, such as a rule controlling the burning of methane on public land by oil and gas companies. This may have consequences within the U.S. as well as for the country’s relationships with other nations, Thomson said.

“If U.S. greenhouse gas policies are watered down under the Trump Administration, we will lose credibility on the international stage,” Thomson said. “U.S. voters — including a clear majority of Republicans — want to continue to move toward renewable fuels and to help mitigate climate change.”

In light of the president’s business-minded orientation, Wolz said he is optimistic for the future of environmental policy.

“You can agree with climate change or not, but solar is cheaper than coal and wind is cheaper than natural gas,” Wolz said. “I'm hopeful that [Trump] will realize the economic value of those.”