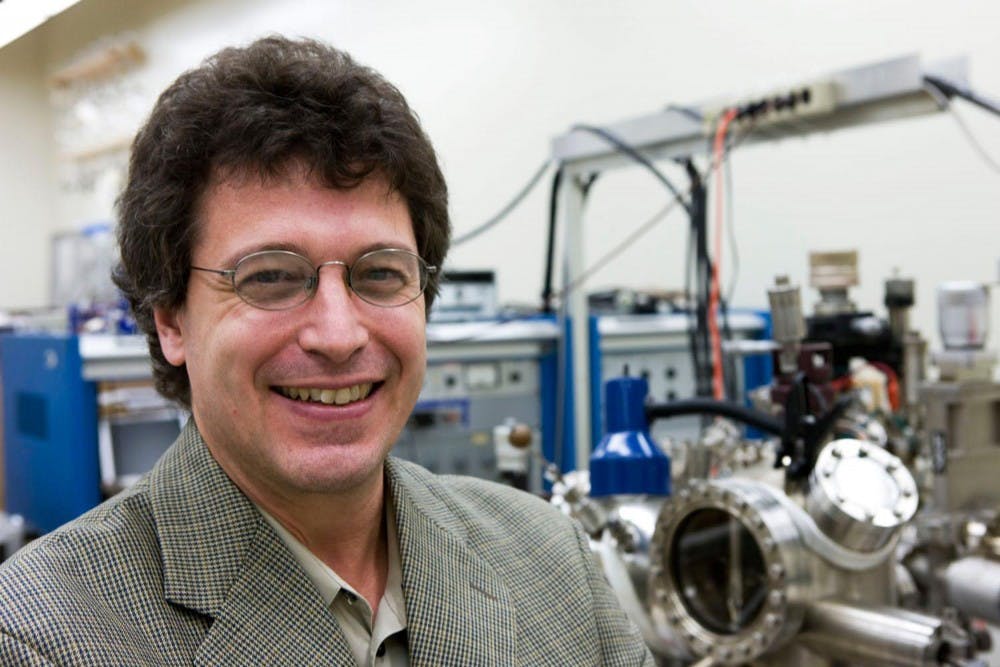

Chemistry Prof. Brooks Pate has won the University’s highest award for faculty innovation. The University’s Licensing & Ventures Group, which seeks to turn ideas and discoveries from the University into marketable products, has awarded Pate with the Edlich-Henderson Innovator of the Year award.

Pate’s research on molecular analysis has led to the creation of a new scientific instrument that significantly reduces the time and cost needed to perform complex chemical analysis. His research discovery on molecular rotational spectroscopy played an integral role in the founding of the local lab firm, BrightSpec, which helped turn the research into an instrument for scientists to use.

Pate said their research on molecular rotational spectroscopy measures how fast molecules rotate.

“The idea is that the sensors become like a molecular ice skater, where the shape of the ice skater determines how fast they rotate,” Pate said. “We measure the frequency to very high accuracy, about eight digits of accuracy. From how fast they rotate, we can back out what their three dimensional geometry was.”

Pate’s research opens new applications for scientists because it advances the ability of those measurements to get information on more challenging systems. The technique they’ve developed, chirped pulse spectroscopy, allows measurements to be taken 10,000 times faster than they’ve been made before.

“The advantage of that is essentially going faster [which] means that at some level you’re more sensitive,” Pate said. “And that really allowed us to open up the technique to look at some relatively challenging problems and how molecules clump together when they come together to form assemblies of molecules and that’s been a very hard measurement to make.”

Brightspec CEO Bob Lloyd helped to bring Pate’s research into the marketplace. Brightspec’s clients include mostly research groups — both federal and academic — in the U.S. and Europe and is working to expand into the commercial pharmaceutical industry.

Lloyd said he wanted to work with Pate for several reasons, including the fact there were three graduate students working in Pate’s lab who were trained in the technique and were looking for a full-time career. Pate’s prototype was also a motivating factor for the partnership.

“And that prototype, that working prototype, we were able to take around to conferences and gauge people’s reactions to it,” Lloyd said.

Three patents were also established and they found people to use the product around the U.S.

“At the end of that process we had all the components we needed to start a company,” Lloyd said. “We had a team, a prototype, IP and people who said they cared from the customer segment.”

Pate credited his award to the involvement of the three graduate students in his work.

“They were able to perfect the instrument and start filling the instruments to companies who were looking for new ways to do chemical analysis,” Pate said. “The award really comes from the effort of my students’ company, and the fact that they’ve been able to take these ideas and create instruments that people can use to solve problems that they couldn’t solve before.”

In the future, Pate will be working more with the concept of isotopic abundances, which might have the potential to explain the origins of molecules.

“We’re now really focused on trying to bring new solutions to the problem of being able to measure isotopic abundances in molecules — the high accuracy,” Pate said. “[This isotopic signature] is something that people think will be very important in identifying where molecules come from.”