University researchers identified a potential signal for neuron death, which could lead to new therapies for those suffering from neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson's disease, in the near future.

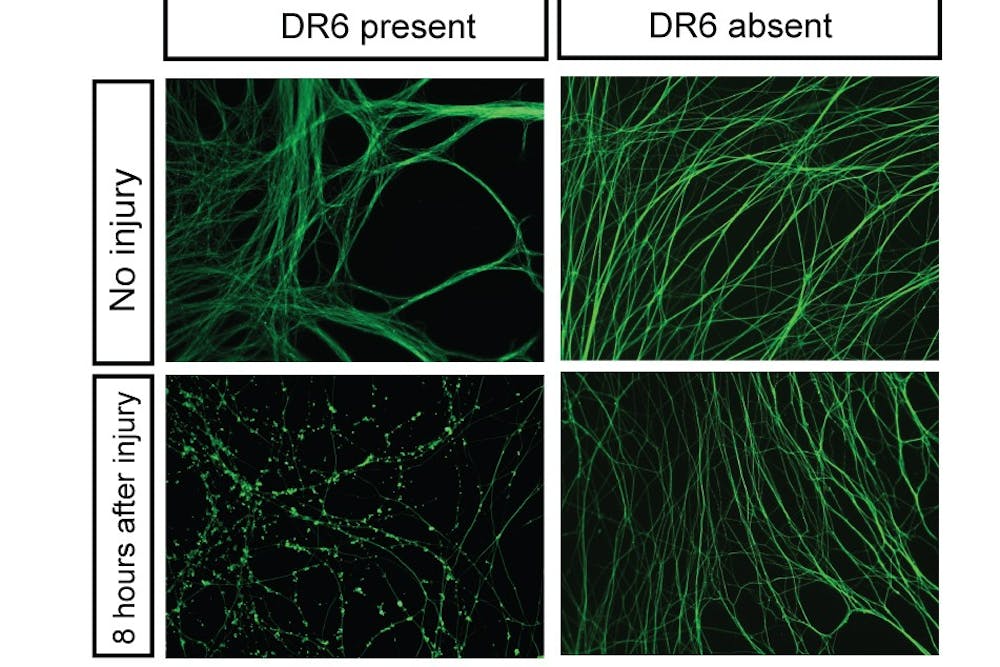

The study, conducted by Assoc. Biology Prof. Christopher Deppmann and graduate student Kanchana Gamage, began with an investigation into the development of the nervous system during infancy. While examining a group of neuron receptors — cell surface structures that respond to stimuli — researchers noticed that binding to a certain receptor in the nervous system results in the degeneration of axons, or the fibers that carry information to the cell.

“We were looking at one particular group of receptors because we have known about this receptor’s involvement in developing the nervous system,” Gamage said. “What we found is there is a receptor which detects outside signals, and it gives the information to the inside of the cell, [saying] ‘okay, this environment is telling me to die.’”

This specific receptor, named Death Receptor 6 or DR6, is found in both healthy and unhealthy neurons, meaning the axons in the cells could consequently receive a signal to die even if the cells are uninjured.

The discovery creates new possibilities for treating conditions such as Alzheimer’s, as inhibiting the detector would help slow the degeneration of axons — a characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases.

“If we could develop a drug which could block this receptor, we could slow down the degeneration and it could be helpful in trauma as well as in diseases like Alzheimer’s,” Gamage said.

While Deppmann said he is unsure whether the discovery will be used for specific investigations relating to conditions such as Alzheimer’s or Amytrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or “Lou Gehrig’s Disease”), the study’s findings have led the researchers to continue their investigating different areas of the body.

“We have a lot of other questions that we need to answer from this finding,” Gamage said. “Our immediate next step is to look at the brain, so if it is the same receptor that works in the brain, it could apply to Alzheimer’s and Huntington's disease. If we found that, it would be helpful for companies who are working on drugs as well.”

Deppmann and Gamage’s research received funding from multiple organizations, such as the National Institute of Health and the Owens family foundation.

“We're really grateful to the NIH,” Deppmann said. “We've followed some of this work up with work on Alzheimer’s disease that was in progress from the Owens family foundation, who's a really generous benefactor to the University.”

Outside of the foundations that provided funding, the team is highly appreciative of efforts made by other researchers, including Psychology Prof. Alev Erisir, who assisted with electron microcopy work. A group at James Madison University also contributed to the axon receptor project, helping create a device designed to control neuronal pattern formation.

The discovery furthers the scientific community’s understanding of the progression of axon degeneration and the developmental processes of the nervous system.

“The great thing about science is that it builds,” Deppmann said. “So something that we put out there somebody else can build on, and we're standing on the shoulders of giants too.”

Correction: This article previously misidentified Assoc. Biology Prof. Christopher Deppmann as an assistant professor, and also misstated graduate student Kanchana Gamage's reference to Huntington's disease as Hodgkin’s disease. This article has been updated with the correct information.