Environmental Science Prof. Howie Epstein oversaw a study that used declassified satellite spy photographs to find changes in Arctic greenery. Epstein and his graduate student at the time, Gerald Frost, identified 11 sites around the Siberian tundra and found the amount of shrubs were increasing in those areas.

Arctic scientists have been observing an increase in vegetation in the Arctic tundra since the early 2000s, Epstein said. However, Epstein said he noticed a gap in observations of shrub expansion in Siberia during the Cold War.

“[Frost and I] knew of of this collection of spy satellite imagery,” Epstein said. “There have been a few other studies that have used this imagery, and so my graduate student decided to take a look at them.”

While unconventional, sources such as the realist paintings created by the Hudson River School in the 19th century have previously been used as scientific evidence. For example, those 19th century paintings of upstate New York depicted a haze before industrialization — something understood now to be produced by trees interacting with the atmosphere — Environmental Science Dept. Prof. Robert Davis said.

“It’s important to have good observations, or you can’t detect the change in anything,” Davis said. “So, sometimes you have to use unusual sources to piece together information.”

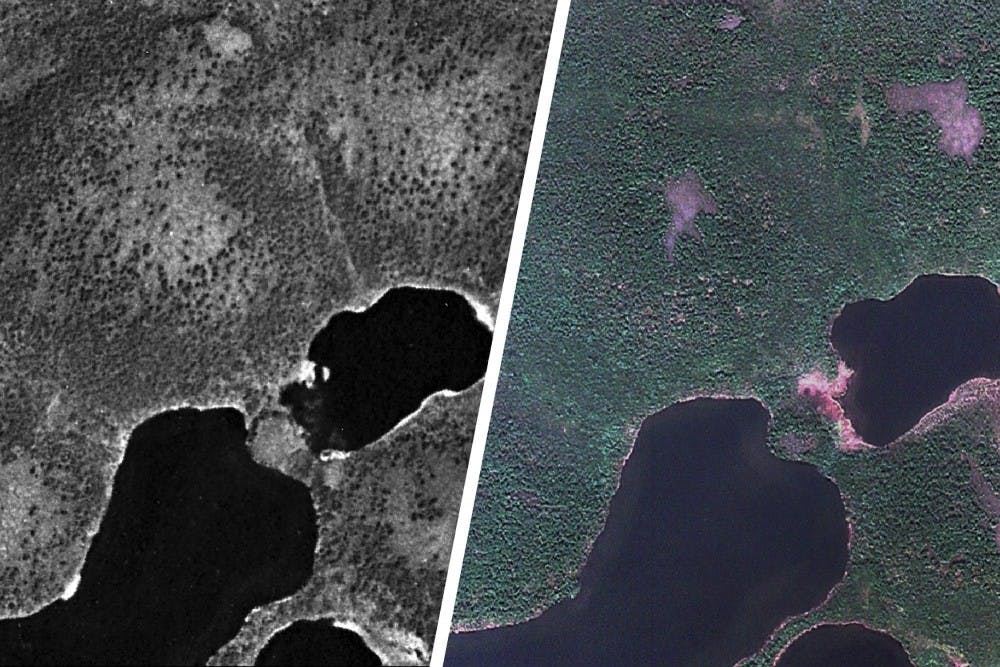

The images used in Epstein’s study were taken by U.S. intelligence on the Soviet Union during the Cold War — using some of the first earth-observing satellite missions, Epstein said. The photographs are grey-scale, but are high resolution.

“You can see down to a meter resolution,” Epstein said. “They were really good at looking at particularly shrubs and trees, and stuff like that. That’s obviously not what the CIA was looking for at the time, but it turns out they’re really good for seeing changes in shrubs on a landscape.”

Sets of satellite images were declassified in 1995 by the Clinton administration and then again by the Bush administration in 2002 — both are available online. From these photos, Frost isolated 11 sets of images across the Siberian tundra, and paired them with commercial high-resolution imagery in order to track greenery changes over time.

“What the data and images are suggesting is that shrubs have increased quite a bit on these landscapes over the past 40 to 50 years,” Epstein said. “If they were in equilibrium in climate, it would suggest that this could be a result of global warming.”

The Arctic is warming at twice the global average, making climate change a likely reason for increasing shrubbery. However, warming disturbances — including fires that clear space for shrubs, the thawing of permafrost and other natural occurrences — may also be at fault, Epstein said.

According to Epstein, an increase in the number of shrubs has both advantages and disadvantages. For example, the insulation provided by the shrubs will keep the ground cooler in the summer, but warmer in the winter. Additionally, snow-covered shrubs reflect incoming solar radiation, but protruding shrubs re-radiate heat — causing additional atmospheric heating.

“It’s hard to say [if it’s] good or bad,” Epstein said. “But if you want to make a call, it ends up being very complicated — particularly depending on what aspect of the ecosystem you care about.”

This complication has also arisen when looking further into other Arctic greenery trends. While Epstein’s study focuses around greening, Arctic browning — or the decrease in shrubs — has also been observed.

“The bottom line is that it’s a very complicated system, and we have a long way to go before we understand what is controlling vegetation changes in the arctic,” Epstein said. “The paradigm that we’ve been operating on is the tundra is greening … But it turns out, it’s not just greening. It’s a lot more dynamic than we imagined.”