On Aug. 12, the “Unite the Right” rally drew hundreds of white nationalists and counter-protesters to downtown Charlottesville. The night before, white nationalists held a torchlit march through Grounds. But this was not the first time that those with controversial beliefs found a platform in Charlottesville and at the University, nor was it the first event to spark a vitriolic debate over the boundaries of free speech on Grounds.

Over 50 years ago, during the spring semester of 1963, two particularly controversial speakers came to the University drawing criticism from all levels of the community.

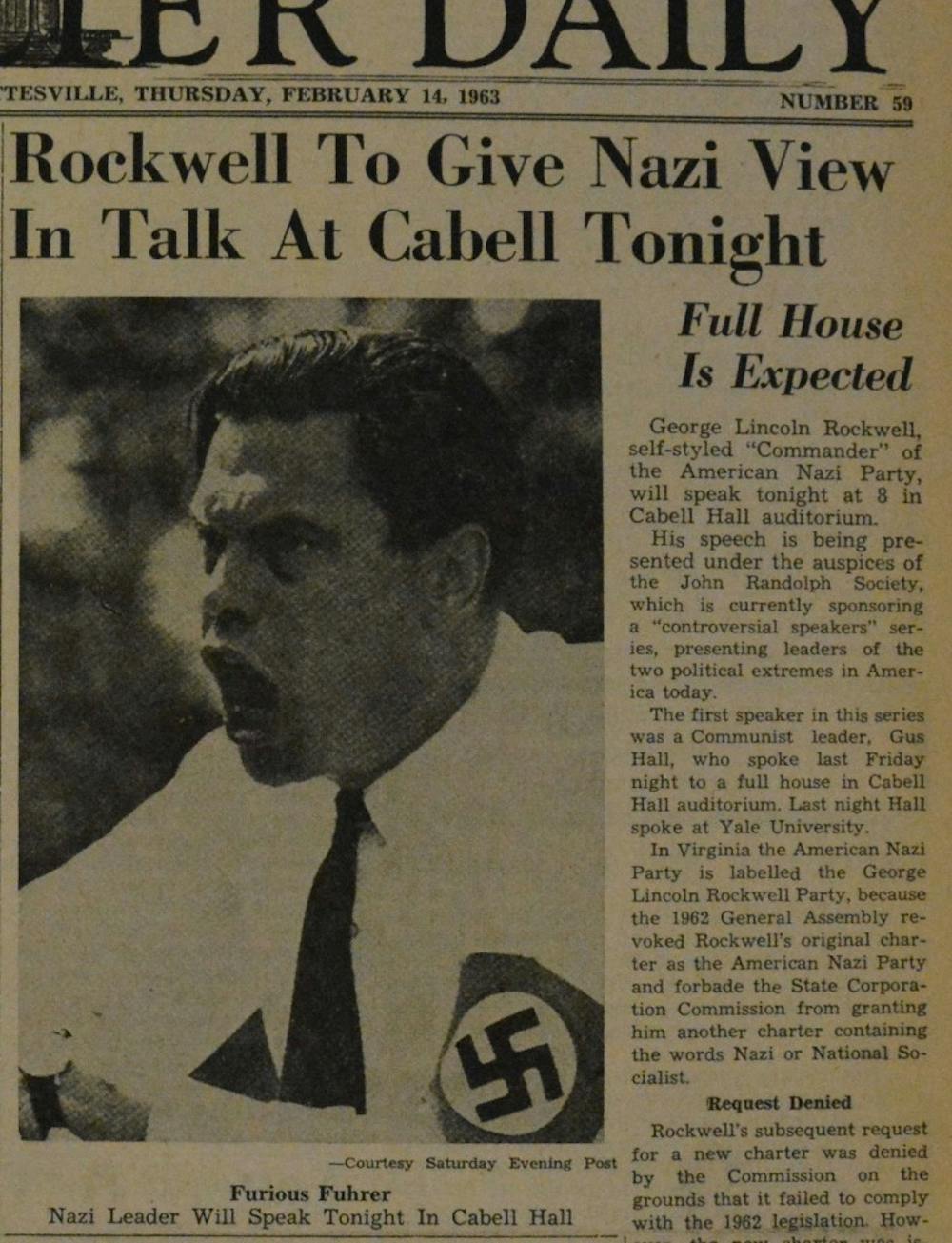

On Feb. 7, 1963, The Cavalier Daily reported that the John Randolph Society, a conservative debating society active at the University in the 1960s, had invited Gus Hall, the secretary of the American Communist Party, and George Lincoln Rockwell, the founder and commander of the American Nazi Party, to speak at what was then known as Cabell Hall (today it is called Old Cabell Hall). The society’s stated purpose of their scheduled appearances was to inform students of the threat posed by Rockwell and Hall’s respective political ideologies.

The Randolph Society invites Nazi, Communist speakers to Grounds

Hall spoke at the University on Feb. 8 and Rockwell came on Feb. 14.

Henry Curry, then the vice president of the Randolph Society, wrote an article in the Feb. 20, 1963 issue of The Cavalier Daily about his experiences meeting Hall and Rockwell in an article titled, “Hall, Rockwell Show Many Differences.” He described them both as notable particularly for the interesting contrast they drew to one another.

“Both Hall and Rockwell had a lot of praise for today’s youth,” Curry wrote. “In his press conference Hall stated that he was glad that today’s young people were probing in both directions — left and right.”

1967 University alumnus Howard Means was a second-year student at the time of Hall’s and Rockwell’s appearances. He recalls the controversy that their invitations caused.

“U.Va. was a much smaller institution then and, of course, deeply conservative, but as I recall, that lineup of speakers briefly brought the place to life and sparked a fairly interesting debate over freedom of speech and related matters,” Means said.

Means is not certain that he actually attended Rockwell’s lecture, but he vividly remembers the audience’s reaction to Gus Hall’s lecture. Although Hall filled the Cabell Hall auditorium to capacity, many of his speech’s attendees found his ideology repugnant.

“There was a lot of booing — I remember very distinctly,” Means said. “I don’t remember if I went to Rockwell’s speech — I found it distasteful to even attend something that featured the Nazi Party. But there was a lot of derisive reaction to it, and I suspect it would have been led heavily by fraternity people in those days — they made fun of him and did the same thing with Gus Hall.”

Stephen Barney, a 1964 University alumnus who attended both Hall’s and Rockwell’s speeches, recalls the student reaction as disapproving.

“Rockwell was the most memorable — he was roundly booed many times,” Barney said. “He cleverly asked the audience who had actually read ‘Mein Kampf,’ and I saw no other hand than mine go up. It is the most boring piece of drivel ever written.”

Even the invitation of these men to the University came as something of a shock to the student body. According to Barney, it was perhaps the controversy surrounding their appearances, or a natural sense of curiosity, that led over 1,200 students to pack the Cabell auditorium on the night of Gus Hall’s appearance 50 years ago.

“I presume that a great many came out of curiosity and the excitement of controversy,” Barney said. “In those days, there weren't that many interesting activities in evenings at U.Va., aside from partying. People tended to go to things, especially if famous people were speaking.”

The Cavalier Daily reported that Hall drew an audience so large, nearly 500 additional students were turned away at the door.

“I mean, this was a bombshell by the standards of what I thought Charlottesville was, what I thought U.Va. was, and it was not to be repeated during my five years there,” Means said. “This was about as political as I saw the school get.”

Gene Blumenreich, another classmate of Barney and Means, recalls some more specifics of Hall and Rockwell’s appearances at the University in 1963.

“Gus Hall was a feeble old man…that was my impression then,” Blumenreich said. “He was clearly no threat to anyone and talked about freedom of speech, which he claimed was being denied to him. I think there were several attempts in the 50s and early 60s to jail him.”

Blumenreich described Rockwell as the more troubling of the two.

“George Lincoln Rockwell was a neo-Nazi, just like the people who marched last Saturday in Charlottesville,” Blumenreich said in a phone interview Aug. 23. “I think he carefully chose what he was going to talk about to take out some of the more racist and obnoxious parts of his talk. So he was a controversial person, but his talk at Virginia was not all that controversial.”

Barney entered the University with the first class of Echols Scholars in 1960 and was a third-year at the time that Hall and Rockwell came to speak. He recalls the large crowds they drew.

“It would not have occurred to me or to any students, I think, that attending these speeches gave any insight into one's political beliefs,” Barney said. “These were big-deal 'events' and inspired curiosity.”

“I always had the impression that the real purpose of the invitation was to test the U.Va. administration,” Blumenreich added. “They passed.”

The University did not prevent these controversial figures from speaking on Grounds. The Feb. 12, 1963, issue of The Cavalier Daily published an article on the controversy.

“In his first public comment on Hall’s appearance, President [Edgar] Shannon stated, by means of sheets given to those entering Cabell Hall, that all members of the University ‘should be able to hear the views of any speaker without interference,’” the article reported.

The Board of Visitors, however, did not hide their disapproval of the Randolph Society’s invitations. The Cavalier Daily wrote about a board resolution dissuading further selection of controversial speakers.

“The Board of Visitors admonished the John Randolph Society, and all other student organizations, to use greater discretion in the future as to the choice of guest speakers,” the article reported.

The Cavalier Daily also reported the invitations of Rockwell and Hall drew criticism from the Richmond Times-Dispatch, which ran an editorial encouraging students to "stay away in droves.”

MLK speaks later that spring

Hall and Rockwell were not the last controversial speakers who would appear at U.Va. that year. That same semester, there was additional controversy when the Jefferson chapter of the Virginia Council on Human Relations invited Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to speak in Cabell Hall. The organization was responsible for bringing to Grounds numerous speakers who opposed Virginia’s racial segregation policy.

Wesley Harris, then-chairman for the Human Rights Relations Council, was instrumental in bringing King to Grounds. Harris graduated from the University in 1964 with an engineering degree and now works as a professor at MIT.

“U.Va. in my experience, 1960-1964, was a very racist environment with little, maybe no, support for African Americans,” Harris said. “There were no black women on campus — or Grounds, as we called it. We were not allowed to major in any of the possible programs in the College. There were no black faculty. There were no black administrators.”

Monty Joynes, another University alumnus who was a student in 1963, said in an email to The Cavalier Daily that he recalls seeing only a single civil rights protest, at the University Theatre on the Corner, during his time at the University.

“Less than five students with placards were protesting that blacks could only be seated in the balcony, not the main floor,” Joynes said. “I remember a great student apathy regarding civil rights. Student priorities were social, not political, from my point of view.”

Although King's speech at Cabell Hall on March 25, 1963 was not met with protests among the student body or administration, Harris said King’s appearance was not greeted respectfully.

“The faculty basically ignored it,” Harris said. “Edgar Shannon, the President, refused to acknowledge his presence on campus. Dr. King didn’t exist in their minds. The leadership of U.Va., they didn’t shake his hand, they did not meet him. They didn’t come to Old Cabell Hall.”

Howard Means recalls the event in similar terms.

“King did not get a full house — he got about 600-800 people,” Means said. “I don’t think people like Edgar Shannon showed up. He was the president then, and he probably should have. It was a kind of passive-aggressive response.”

According to Harris and Means, the University was a dramatically different institution 50 years ago, at a time when the Civil Rights Movement was gaining traction and Virginia was still in the middle of massive resistance to it.

“I do put Martin Luther King, Jr., in a different category [than Hall or Rockwell], because while he was controversial at the school at the time, it was because of the extremely conservative people in the student body and not for what he said or did,” Blumenreich said. “I think it’s clear that history has borne out his position.”

The community’s response to Rockwell and Hall

Although their opinions were expressed quite differently, University students in 1963 looked upon Rockwell with similar distaste as most students today look upon David Duke.

“The student response today appears to be vocal,” Means said. “It was not terribly vocal at that time, and it was still fairly shackled to conservative ideology and conservative convictions. There weren’t people marching around in torchlight parades up and down the Lawn to protest or to support George Lincoln Rockwell’s presence. It was an understated reaction.”

Following Hall’s appearance in Old Cabell Hall, newspaper headlines reported that his appearance had caused no violence. The Feb. 12, 1963 issue of The Cavalier Daily published several articles on his address to Cabell Hall, noting the absence of rioting.

“The only tangible sign of protest came from picketer Henry Methot of Alexandria, and according to the sign he was carrying, his target was more [Soviet Union leader Nikita] Khrushchev than Hall,” the article reported.

The Cavalier Daily archives contain numerous op-eds expressing a wide range of opinions on the speakers’ appearances. The letters to the editor included in the Feb. 12 publication express a variety of viewpoints and arguments.

John D. Kenny, then a third-year student in the College, wrote a letter to the editor titled “Rational Study.”

“It is the duty of society to actively encourage all forms of expression however repugnant they may seem so that these doctrines may be judged by their own lights,” Kenny wrote.

Another student, then first-year law student Edward H. Powers, echoed Kenny’s sentiment in another piece titled “Right to Speak.”

“The important point is not what Gus Hall said, but that he was allowed to say it,” Powers wrote. “His views were rejected, but at least they were heard.”

Robert Langbaum, an associate English professor, held a different opinion.

“There is no question here of giving Rockwell’s ‘ideas’ a hearing, since he has only one theme — hate,” Langbaum wrote in a letter to the editor. “The John Randolph Society exercised its prerogative of inviting the man. The rest of us ought to exercise our prerogative of staying away.”

Distaste for Rockwell and Hall seems to have been nearly universal among University students at the time, but there remained a diversity of opinion about how to react to their appearances on Grounds. Some students advocated boycotting the talks, while others attended. Although many of the University’s students at that time disapproved of Communism and Nazism, Hall and Rockwell still managed to fill their lecture halls.

The University considers a path forward

In a letter to the University community on Aug. 18, President Teresa Sullivan announced the founding of a working group of deans and other University community members to lead the University's efforts in assessing future responses to events such as the rally on Aug. 12. The working group will be chaired by Law School Dean Risa Goluboff.

Goluboff also wrote a letter to the University community in which she described the working group’s plan to reallocate certain resources toward both short and long-term solutions.

“The General Counsel’s office is already exploring revisions to our policies regarding activities that can be constitutionally proscribed on our Grounds,” Goluboff wrote. “The University is assigning significant resources, additional staff members and police, both visible and not visible, to ensure safety and security across Grounds as the semester begins.”

Goluboff described the tasks ahead of the committee as geared toward both the short-term and the long-term, all concerned with the security of the University and its students — not from the danger of disagreeable ideologies, but from physical danger, so that students and the broader community may continue to engage in respectful and productive dialogue.

“Going forward, we intend to use the energy unleashed by this moment to advance the University’s commitment to democracy, social justice, inclusion, and equity,” wrote Goluboff. “We have at our disposal the personnel, the will, and the resources to do not only what is needed but what is right.”

Correction: The article previously misnamed Monty Joynes.