On Monday, Aug. 21, concerned and outraged members from across the Charlottesville community took to City Hall to express their grievances to City Council regarding the “Unite the Right” rally of the previous week. The attendees targeted the Council as a whole for failing to prevent the outbreak of violence during the rally, and then went on to single out the failures of Charlottesville Mayor Mike Signer and University President Teresa Sullivan to prevent white supremacists from confronting counter-protesters. The meeting quickly devolved into chaos, resulting in the abandonment of the Council’s procedural norms, and the chance for every aggrieved citizen to voice their complaints for one minute. This chaotic example of mass participation at the local level typifies the level of civic involvement the city of Charlottesville and cities across the country should strive for, in order to combat fringe groups attempting to dominate over the voices of many.

Town hall and city council meetings in the United States offer a unique platform for elected local officials to interact directly with their constituents. This direct line of communication not only allows local politicians to gauge public opinion within their community, but also, perhaps more importantly, allows their community to hold them accountable for decisions made in office. Civic engagement with one’s representatives is built into the very fabric of the United States government, with roots tracing back to colonial autonomy and the resistance of British virtual representation. Through the formatted exchange of ideas, citizens and elected officials alike can successfully minimize discrepancies between public will and governmental policies.

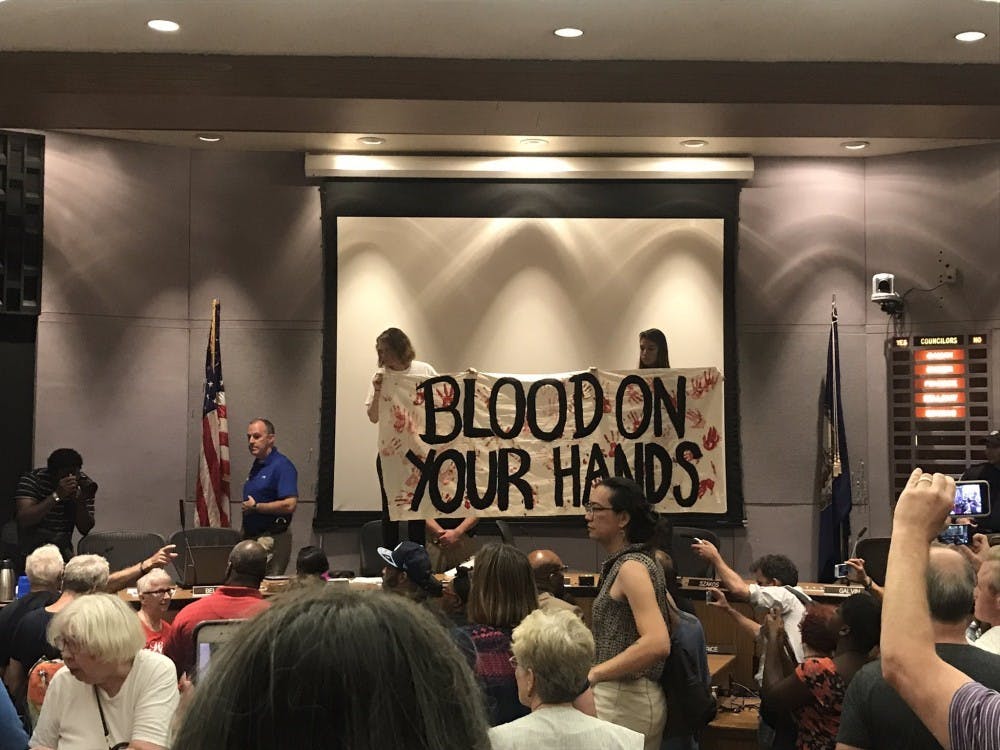

Extreme tension between public will and government decisions came to fruition during the Charlottesville City Council Meeting as audience members demanded the resignation of Mayor Singer and chants of “Blood on your hands!” broke out. While the hectic environment of the meeting culminated in three arrests, it accurately reflected the larger sense of frenzy the Charlottesville community has experienced in wake of the white nationalist rally and ultimately resulted in a call to action.

In response to constituent demands, the Council members voted to begin the removal process of a statue of Confederate general Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson in accordance with their earlier decision to remove the Robert E. Lee statue. The Council also voted to shroud the statues in black in show of mourning. Additionally, the city manager promised a third party investigation of measures taken by the local government in response to the rally. The Charlottesville community exacted tangible action from their elected officials, demonstrating the major influence voters have when threatening their representatives’ reelection.

Across the country, other communities are following suit and exercising their civic duty. In Fayetteville, N.C., Rep. Robert Pittenger, R-N.C., engaged in a heated exchange with Town Hall attendees in support of the removal of a Confederate Statue. The platform enabled Pittenger to not only respond to their questions, but also to counter them in furtherance of the conversation. In a similar vein, the San Antonio City Council voted for the removal of a Confederate monument following the Texas city’s rally to preserve the monument on Aug. 12.

Unlike rallies, city council meetings attempt to offer the community with diverse viewpoints in a controlled environment. Civic engagement effects change at the most fundamental level of U.S. government. The Charlottesville City Council assembles in City Council Chambers in City Hall, 605 East Main Street. As members of the Charlottesville community, University students ought to hold their public officials accountable in order to continue to move forward from the horrific events of Aug. 12.

Charlotte Lawson is an Opinion columnist for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.