“What we are doing is to help the Cambodians help themselves,” then-President Richard Nixon says over the tempered pulse of “Sympathy for the Devil” by the Rolling Stones. Meanwhile, a United States warplane flies over trees which alight with its bomb-fire. “This is not an invasion of Cambodia,” Nixon says.

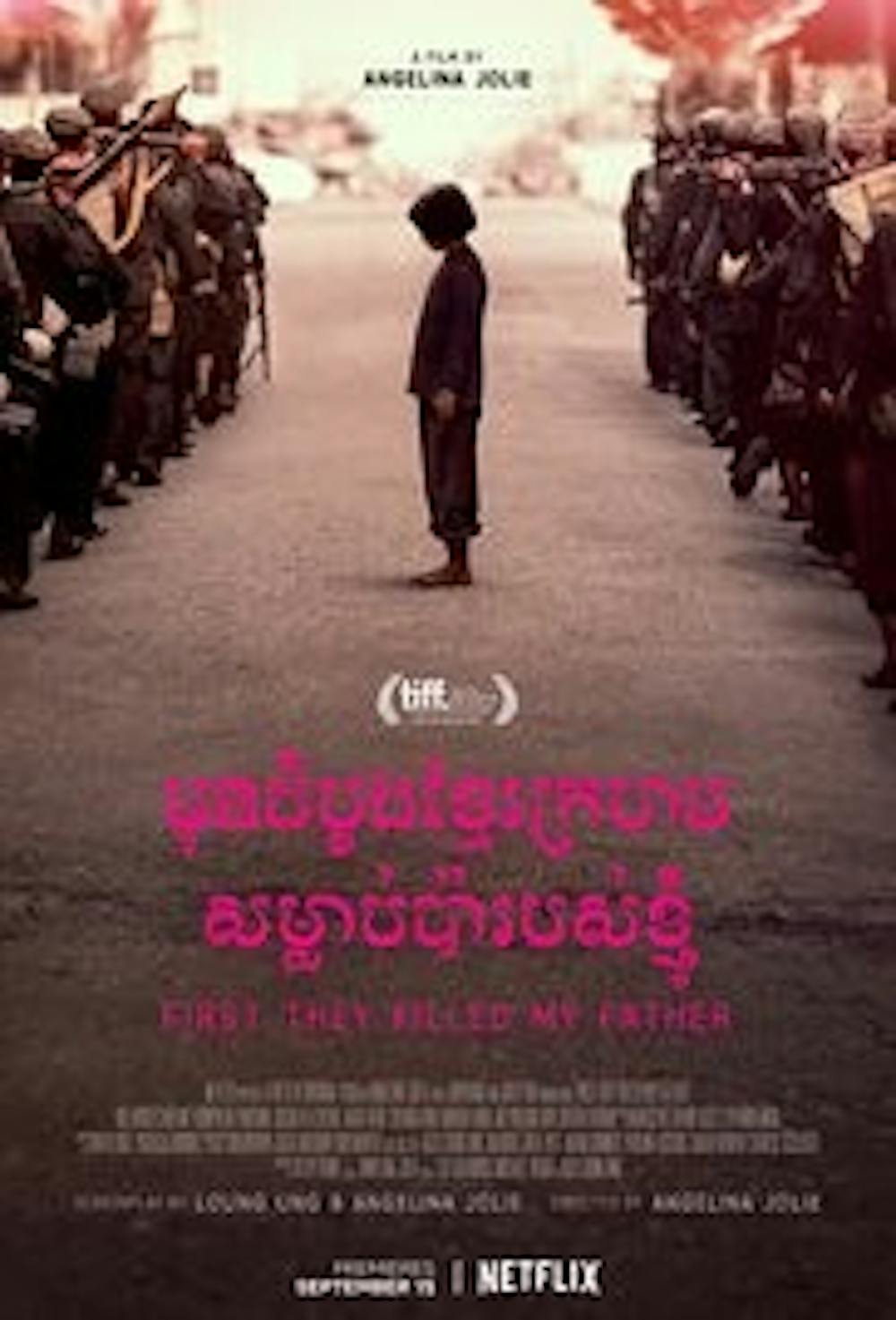

It is an uncomfortably familiar opening for an American audience reared on equal parts exceptionalism and violence, yet “First They Killed My Father,” a Netflix original film directed by Angelina Jolie, is less concerned with blame than it is with paying homage to all who suffered under the reign of the Khmer Rouge. Once this newsreel sketches a historical context, the film defers to the eyeline of five-year-old girl Loung Ung (Sareum Srey Moch), who must fight for survival after Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, falls to insurgents.

The real-life Loung Ung, who is now 47-years-old and wrote a book of the same name, shares screenwriting credit with Jolie. Of the duo’s utmost concerns is a respect for and adherence to Cambodian life — the film is shot entirely in Khmer, the Cambodian language, with English subtitles. Such a choice is not a deterrent to an English-speaking audience, however, as the child’s perspective relies less on dialogue than it does a roving, restless camera. This flittish, unsure gaze gives rise to a heightened childhood paranoia that has the viewer tensing for blows that are not coming — for broken ribs, rapes, explicit deaths — because while mature audiences expect this of war, the innocent Loung does not.

Only then does the viewer begin to fully realize the machine guns swaying on hips, the near-empty food pails, the kneeling children. It creates an unabated terror, an unconscious lean toward the screen, though the film exercises impressive restraint in its portrayal of violence. Early deaths are quick, unadorned and shown for what they are, as well as for their insignificance in the eyes of the Khmer Rouge, rather than milked for a sickening, Rotten Tomatoes currency.

Instead the film’s imagery is surreal, often alternating between the saturated, lucid-dreamlike green of the tropical Cambodian landscape with the human horror of the work camps. It is a reminder that Cambodia itself is not an inherent land of ruin — it is the country’s people who have come to carry their own ruins, whether of state or of family. Against this scenery, the moments between persons feel much more intimate, which only underscores that this is not a wallpaper-paste historical film. This is a study in the resilience and love of family.

It is a story about parents aching to take care of their children and the agony of being unable to do so, and conversely, it is children watching their parents, the ones who know everything in their worlds, break right in front of them. The film’s most heartbreaking moments, therefore, are also its smallest. When Loung’s sister falls severely ill, her mother runs to meet her in a medical tent where a patient uses a glass Coca-Cola bottle in place of an IV bag. The mother bows over Loung’s sister and cradles her face in her hands.

“Ma’s here,” she says. “I am going to take care of you.”

This recurring self-sacrifice, the need to protect and to save — even when such actions are hopelessly futile — is a searing reconciliation with the humanity audiences lose digesting history only through a Nixon newsreel. The passion behind this film is what drives its success — grief, after all, is without boundary. Loung, Cambodian producer Rithy Panh and Jolie, who has Cambodian citizenship and adopted her oldest son Maddox from the country, elicit empathy from even the most distant audiences. The film’s tagline is “A daughter of Cambodia remembers so that others may never forget,” and it closes with these words. The never-known, however, cannot be remembered, and with “First They Killed My Father” already streaming on Netflix, audiences can be exposed to a frequently forgotten tragedy of history.