Walking into the anatomy lab in Pinn Hall, the smell of formaldehyde penetrates the air. The voice of Amy Winehouse plays softly in the background, weaving in and out around the sound of metallic tools. Three, then four, Medical students in green surgical gowns lean with lab glasses and gloves over three deceased human bodies — “cadavers.” Their task for the day? To remove the brains, allowing for an identification of the local structures and associated vessels and nerves.

David Moyer, assistant professor of medical education and director of Gross Anatomy Education at the School of Medicine, introduces the students and gives a brief tour of the anatomy-dedicated laboratory spaces while they get to work on their cadavers.

These days, the University purchases cadavers from the Virginia State Anatomical Program, which supplies the donated bodies to medical and academic centers throughout Virginia for medical research and anatomical studies. The program was established about a century ago, in 1919. Before this, largely throughout the entirety of the 19th century, medical centers chose to partake in grave robbing to facilitate such studies.

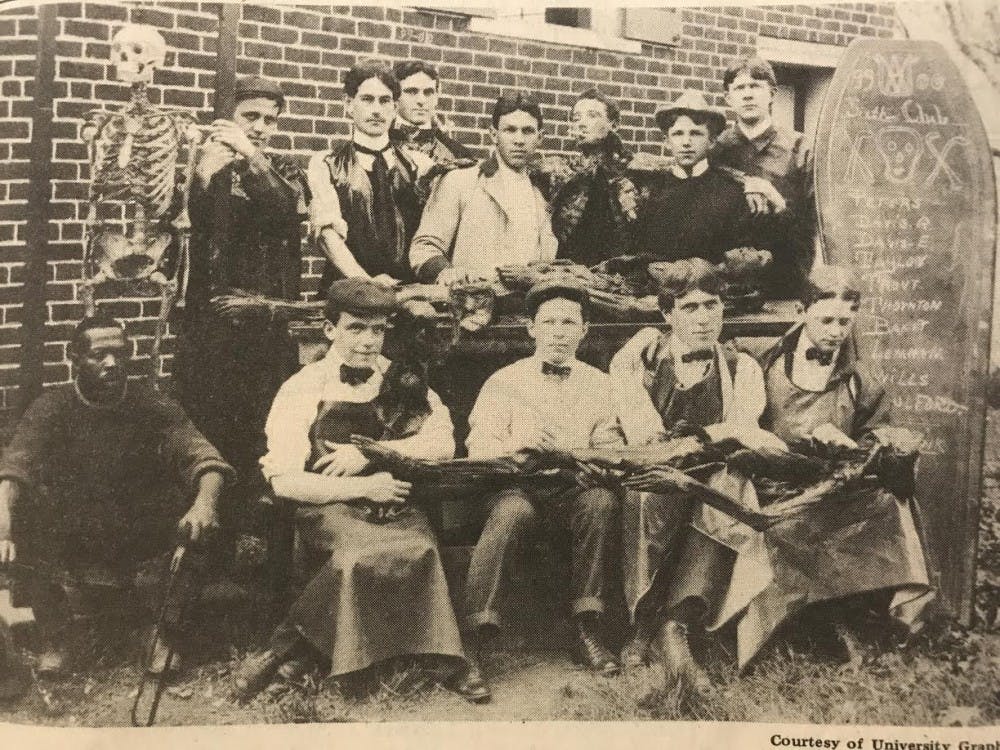

19th-century anatomy

In the early years of the University, Thomas Jefferson started the anatomy program in an attempt to take the European Enlightenment model of education and move it forward into the realm of modern scientific studies, said Kirt von Daacke, an assistant dean and history professor. One of the core hypotheses when founding the program was that there would be a clear difference, upon investigation, between the anatomy of black bodies and the anatomy of white bodies.

Such anatomical investigations would require human subjects, so — since there was no way to embalm bodies in the early- and mid-19th century — grave robbing became a standard practice in medical schools across the United States, according to von Daacke.

“This is going on in Richmond, in Alexandria, in Baltimore, in New York, Norfolk — [grave robbing is] going on anywhere and everywhere,” von Daacke said. “It’s serving medical schools wherever they exist.”

The rich would build mortsafes — cages that extended into the ground and connected to or reached under the casket — over the graves of their deceased to keep grave robbers out, or have someone guard the grave for three to four days until the body putrefied and was no longer desirable for anatomy studies. Because poor and enslaved communities did not have the money to afford mortsafes and could not spare the time to guard the graves of their loved ones, these communities were disproportionately victims of the frequent grave robberies of this time period, according to Von Daacke.

“If you are poor, or you are a member of a dominated or subjugated class — the enslaved, free people of color, poor whites, orphans, anyone in an urban area who is property-less — you’re buried in a potter’s field or you don’t have the money [to prevent grave robbing],” von Daacke said.

At the Medical College of Georgia, where the anatomy department kept a tight record of information on their cadavers, upwards of 80 percent of cadavers used were African-American. According to von Daacke, these rates were likely mirrored in the bodies obtained by the University Medical School at the time.

Through the late 1800s, the University viewed grave robbing in the context of anatomical studies as a normal occurrence, something not worthy of punishment, von Daacke said.

In 1835, there was a case where the owner of a local plot of land, James Oldham, shot a University student who was trespassing and grave robbing on his property. The University’s response to the matter was that the state should prosecute Oldham — that the students had done nothing wrong.

Although the landowner was eventually acquitted, the University made clear its position on grave robbing. As von Daacke put it, the University found the grave robbing practices acceptable because they were carried out in the name of science.

Even as laws emerged concerning grave robbing, the University continued the practice — using pseudonyms in correspondence about cadaver sourcing and working with organizations of professional grave robbers and with the railroad companies that would deliver the bodies to ensure that their activities remained confidential.

According to von Daacke, the practice of medical centers using grave robbing to obtain cadavers continued throughout the 19th century.

“Everybody is kind of in on this, and at one point they are talking about wanting to get 100 bodies a year,” von Daacke said. “This is a practice that continues after the Civil War, here and elsewhere.”

21st-century anatomy

The current anatomy spaces at the University Medical Center enforce rigid protocols and restrictions. All bodies studied at the University, these days, come from the Virginia State Anatomical Center and are willingly donated by individuals while they are alive. Further demonstrating the movement away from those 19th-century attitudes surrounding human dissection, Moyer emphasized the importance of sensitivities towards both the cadavers and the families of the deceased.

Beyond the cadavers themselves, though, the anatomy curriculum also has changed drastically since its introduction. Besides the formaldehyde-embalmed, more traditional cadavers often used in the lab, “soft-embalmed” cadavers are also utilized.

“These [soft-embalmed] cadavers are the game changers,” Moyer said. “This type of embalming is changing the face of anatomy.”

These cadavers — which are “pliable” and “mobile,” according to Moyer — facilitate the study of not only traditional anatomy, but also clinical procedures.

Originally designed to be a “fresh,” or frozen, cadaver lab, the Surgical Skills Training Center, only a few steps away from the gross anatomy lab in Pinn Hall, was converted by Orthopedics Chair Bobby Chhabra and others into a learning environment for medical students, residents and fellows. The space uses soft-embalmed cadavers — and less often, fresh cadavers — to facilitate practice with performing clinical procedures like ACL reconstruction, intubations and tracheostomies, and with using scopes — or cameras — to look at the gastrointestinal tract, knee and other places.

While similar spaces are not uncommon at other medical centers, oftentimes their availability to medical students are largely limited.

“There are schools who have this, but I think what’s happening, more so, is the first-through fourth-year students aren’t getting the chance to do these things — it’s residents and fellows who have the chance,” Moyer said. “I’m trying to give them opportunities that they wouldn’t normally have until residency.”

In addition, generally such spaces are not located so proximally to the gross anatomy lab. Moyer emphasized the importance of this proximity with respect to the “Next Generation” curriculum adopted in 2010, which focuses primarily on a system-based approach.

“So we have a system called the Musculoskeletal System and Integument, and so [the students] are out there dissecting the knee on their cadaver,” Moyer said. “And the same day they’re doing that, they’re coming in here in small groups. We had two cadavers set up with residents here, with orthopedic residents, and they were helping the students drive the camera into the knee joint.”

Moving forward, Moyer hopes to further incorporate soft-embalmed cadavers, and more activities in the Surgical Skills Training Center, into the Medical School’s anatomy curriculum.

“That’s the future,” Moyer said. “Seeing the anatomy laid open is one thing, but seeing it through the camera — when you don’t know if you’re up, down, left, right, backwards — it’s totally different.”