Founded to improve the quality of education for University medical students, the University Hospital and Health System have been on the forefront of the growth of modern medicine and more recent research and discoveries.

From the start, the University Health System has continually increased the number of beds it can hold to better serve the population — both from local communities and statewide.

“As an academic health system, our three main priorities are providing the highest-quality patient care, making research breakthroughs that improve the human condition and training the next generation of healthcare workers,” Eric Swensen, a spokesperson for the University’s Health System, said in an email to The Cavalier Daily.

Currently, the University’s Health System consists of the School of Medicine, School of Nursing, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, Medical Center and the University Physicians Group.

The Health System also includes the Faculty and Employee Assistance Program, which serves both the University and other employers in the community, Swensen said.

According to Swensen, though some care is provided for students through the Medical Center, such as emergency treatment, Student Health is mostly separate from the Health System.

Though it was always a statewide hospital, the University Health System had humble beginnings and a rocky start.

In 1825, Thomas Jefferson began the medical education and patient care program at the University.

“They had a student infirmary starting in the 1850s. By 1901, the members of the medical faculty did rotations as the university physician,” said Dan Cavanaugh, curator of Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library.

However, a dispensary and surgery center was not built until 1895. It eventually served outpatient care for 21 years. This was done to improve medical education at the University, and to give students more than just lectures to learn from, according to Cavanaugh.

Hospitals at that time had a stigma. Physicians would regularly visit patient homes — if they could afford medical care — and going to a hospital implied that someone could not provide for themselves or their family.

“Hospitals were considered among the general population as places only the most disadvantaged citizens would come to,” Cavanaugh said. “They weren’t places to get advanced medical care or advanced treatment.”

The rise of modern medicine at the turn of the century, with advancements in fields like surgery and antiseptics, began to convince the general population that hospitals were good places to access health care.

The Commonwealth originally did not want to build a hospital in Charlottesville, but the University wanted to provide more than just lectures to medical students.

After much lobbying by the University, the second state-funded general hospital in Virginia was built in Charlottesville, to serve patients who could not afford care otherwise.

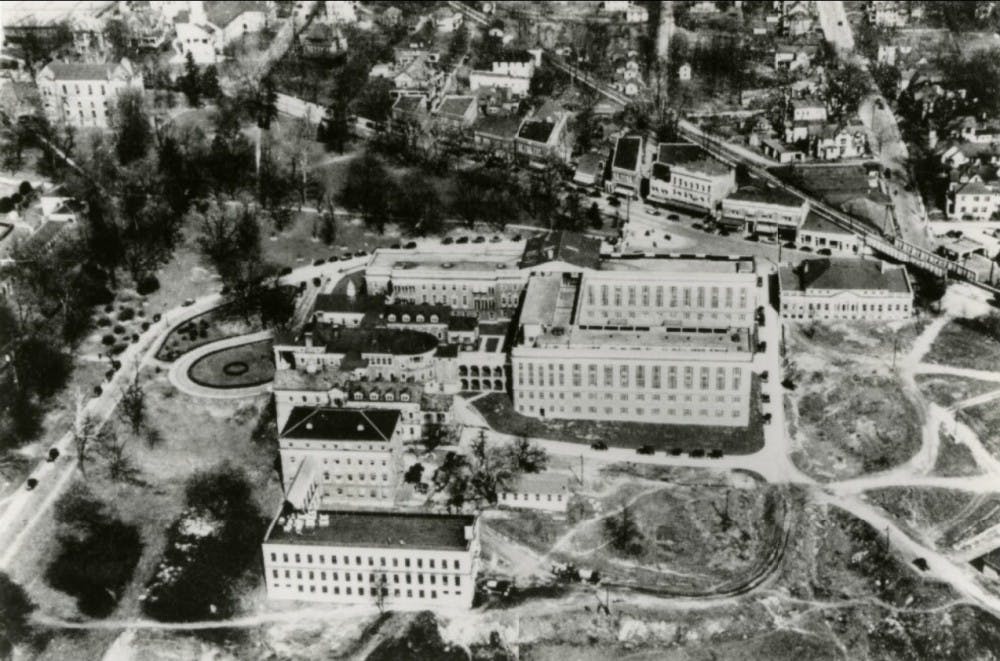

The hospital opened in 1901 with 25 beds. According to the history page of the University Health System’s website, increased funding helped the hospital expand to over 200 beds.

“In 1923 [the state] almost shut [the hospital] down and consolidated it with Richmond,” Cavanaugh said. In spite of this, because of continuous overcrowding, several more expansions were done over the next decades, with a bed count of 485 by 1941.

Other reasons for expansions were advancements in the study of medicine and available technologies.

“Year to year — there are complete changes in how medicine is practiced,” Cavanaugh said. “What’s going to occur is they’re always going to need new facilities for new technologies … they’re going to need new types of wards.”

The West Complex building’s numerous add-ons show the changes the hospital underwent between opening and 1989. The University relied on the state and philanthropists for funding.

“There’s this constant kind of struggle to keep up with the demands and keep up with the changes in technology and changes in the practices of medicine,” Cavanaugh said.

In the hospital, there were private rooms for those who had the money, and public wards where patients were kept in large common rooms.

“If patients couldn’t pay then they would be admitted and the cost would be taken up by the University and then hopefully reimbursed by the state,” Cavanaugh said. “There were times where the University was trying to take as many patients as possible and where there was difficulties in trying to find funds … they didn’t want to turn people away.”

By the late 1970s, expansions had crossed Jefferson Park Avenue. In 1984, construction began on the new University Hospital building — the complex that patients are treated in today.

“Outpatient clinics, offices and research labs are now in what was the old hospital, the West Complex,” Cavanaugh said.

More than 100 years after opening, the 2017-18 U.S. News & World Report “Best Hospitals” guide ranked the University Medical Center as the best in Virginia, with treatment for several specialties ranking in the top 50 nationwide.

The Health System’s website cites operating costs for 2016 as $1,442,141,973. Employed last year were 890 full-time faculty, 709 residents or fellows and 2,164 professional nurses. Eight hundred ninety-four volunteers also logged 84,894 hours in the hospital.

As of today, the hospital is working on new expansions — in bed space and facilities and in connections with health care systems throughout Virginia.

Cavanaugh says that the Health System is building a “larger, wider network” with other medical centers in the state.

“We have formed a comprehensive research and education partnership with Inova Health that will include a research institute and regional campus of the U.Va. School of Medicine,” Swensen said. “We are also looking to extend the reach of both our patient care and research through an array of other partnerships.”

Within the hospital, the Health System is upgrading and expanding their Emergency Department with more beds, more room for mental health services and additional space for assessing patient status.

The Health System is also working on expanding interventional services for patients, as well as building a six-story tower on top of the Emergency Department for patients who need a lot of equipment or private, isolated rooms, Swensen said. The expansions will be completed by the end of 2019.

According to Swensen, those updates are just a few of many changes “to best serve our patients, students and researchers” in the future.