Author and lecturer Lawrence Ross presented his “Blackballed” lecture to students and spoke about ways in which individuals can first recognize racism, then make the decision to become anti-racist in their thoughts and actions.

The presentation was co-hosted by the Multicultural Greek Council, the Minority Rights Coalition, the Inter-Fraternity Council, the Inter-Sorority Council, the National Pan-Hellenic Council and the Black Student Alliance.

“There will never be a n—r in SAE, There will never be a n—r in SAE … You can hang him from a tree, but they’ll never sign with me, there will never be a n—r in SAE,” Ross sang, referring to a chant repeated by University of Oklahoma students in a 2015 video of fraternity brothers on a party bus that went viral.

Ross opened provocatively to introduce a theme that he would incorporate throughout his presentation — students should not be surprised when they witness racist acts. He used media reactions to the OU incident to explain the phenomenon he has dubbed, “three izes equal a miss.”

After racist events occur on college campuses or in organizations, Ross argues, groups enact the “three izes,” by attempting to “individualize, minimize and trivialize” the situation. The reaction to the OU incident underscored his theory — news outlets were quick to call the student young and remind the public of his innocence, state that it was an “isolated incident” and that it could be tied to pop culture references, like the use of the n-word in rap songs.

While these “izes” may seem to hold in individual situations, Ross argued, they lose their luster when applied to historical race-related incidents, like the 1963 Birmingham church bombing, when rap did not exist.

“You effectively disMISS the concerns of black, Latino, Asian and Native American students,” Ross said, by implementing the “three izes.”

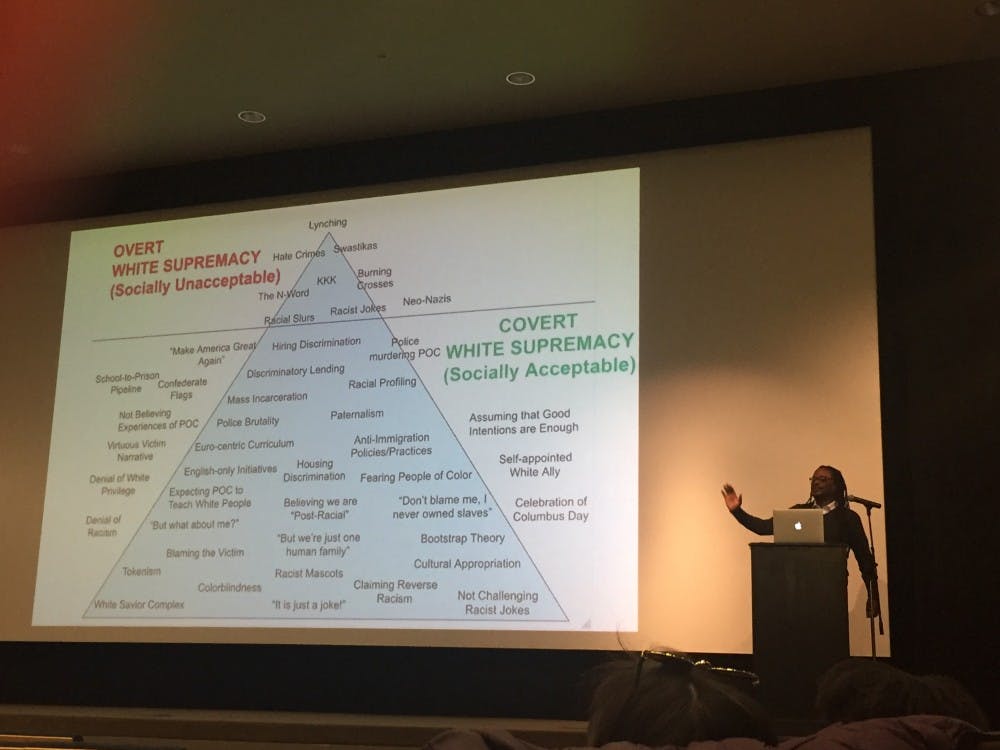

Ross engaged the audience by listing numerous recent race-related incidents, then tying them back to their historical roots to prove that they are not “isolated incidents,” but perpetuations of white supremacist beliefs at America’s foundation.

“When we talk about white supremacy throughout American history … we have to recognize that American society at foundation was geared toward whites,” Ross said.

Ross denounced “color-blind” believers, who say that they do not see race.

“Race is a biological nothing, but is a very important sociological something, and if you ignore the sociological something, you’re doing me a disservice,” Ross said.

Ross discussed the underlying issue that many colleges do not recognize issues with racism.

“We all thinks racism equals cancer,” Ross said. “A lot of our universities don’t realize that they’re sick.”

He said that after recognizing the problem, addressing its possible solutions presents another set of challenges.

“People don’t want to talk about what it really takes to change racism on college campuses,” Ross said.

He spoke about historical legislation, such as the Naturalization Act of 1790, as well as the primary push for affirmative action, later anti-affirmative action pushback and constant presence of racist symbols.

“If you have symbols that denigrate people of color, you’re telling them that they don’t belong on campus,” Ross said.

In reference to statues commemorating Confederate soldiers, Ross compared their presence on college campuses to another example of a historical figure, asking what individuals would think if Jewish students at the University of Munich were forced to walk past a statue of Hitler everyday on their commute.

“You’re in a campus steeped in history, but what is the history that you actually want to keep?” Ross said, specifically referring to students at the University.

He offered numerous visuals of college students’ snapchat selfies of themselves in blackface or posing in racist costumes, in which they depicted scenes of black minstrelsy and explained why he shies away from euphemisms for the n-word in his lectures.

“I want you to understand the ugliness of the words and how they were meant,” Ross said.

Third-year College student Ashwanth Samuel, who is also the incoming IFC President, said he appreciated Ross’ relevance and accessibility.

“Ross was incredibly bold and direct. His message was not ambiguous and I think this is really important when discussing topics as sensitive as this,” Samuel said in an email to The Cavalier Daily. “It was a wake-up call for those who were blissfully ignorant towards campus racism and an affirmation of effort for those who are already working to combat it.”

Ross described “institutional memory” and the notion that groups cannot simply say they were “racist in the past, but good now.” He stated that members of any organization must not only condemn racism, but take proactive, “anti-racist” measures.

“Do not take comfort in the fact that you’re not racist … you have to be anti-racist, the same way you have to be anti-homophobic, anti-Islamophobic,” Ross said.

He said that members of any organization know their peers and must be one step ahead of those they know possess racist beliefs. He called on students in the greater college environment to look at themselves as having the opportunity to gain the resources and education to change systemic issues others — without the privilege of these tools — cannot.

“What we want to be able to do is be so anti-racist that we want to eliminate the idea that racism has any role on a college campus,” Ross said.

He ended the lecture reminding audience members that it is not minority students’ responsibility to teach white students about these issues — all students must take action within their own organizations.

“I think something that’s been important, especially after August 11 and 12, it seems like it’s been such a big focus on Charlottesville itself, as like the only campus in the nation having these racial issues and micro-aggressions,” said Kayla Vincent, a fourth-year College student and vice president of BSA. “I think that he was able to show quite well that it happens literally everywhere across every campus”

Samuel agreed with Ross that there are concrete ways to address racism in Greek life and in day-to-day interactions.

“It's about speaking out when you hear something questionable, taking advantage of teaching moments and humbling yourself in order to empathize with and learn from others' experiences,” Samuel said.

Rory Finnegan, a fourth-year College student and president of the ISC, described a developing monthly dialogue program in which ISC members will discuss some of the issues Ross mentioned on a regular basis.

“The timing of Lawrence’s lecture was certainly considered, and a big reason I wanted it to occur before ISC recruitment was to help spark meaningful conversations among chapter women about inclusivity and bias,” Finnegan said in an email to The Cavalier Daily.

Isaiah Walker, a fourth-year College student and president of the NPHC, said he hopes legitimate change will come from the dialogue.

“My hope from this is that people understand that campus racism, is not something that’s an isolated incident, and that, just because it didn’t happen in your chapter specifically doesn’t mean that it’s … not present,” Walker said. “I’m hoping that people are more self aware and just like understanding that everyone plays a role in preventing racism and stopping it.”