Though some might argue that art and politics are in direct opposition, their relationship is, in reality, much more complex. As the past few months in Charlottesville have undeniably proved, art can be a response to political events — especially political crises. Art has the potential to be a means of understanding or analyzing some of the more baffling political events of history, or a means of satirizing visible political trends. The Arts and Entertainment editors have compiled a list of some of the most well-done political movies in existence — whether they be dark comedies, recountings of political events or realistic imaginings of what could be.

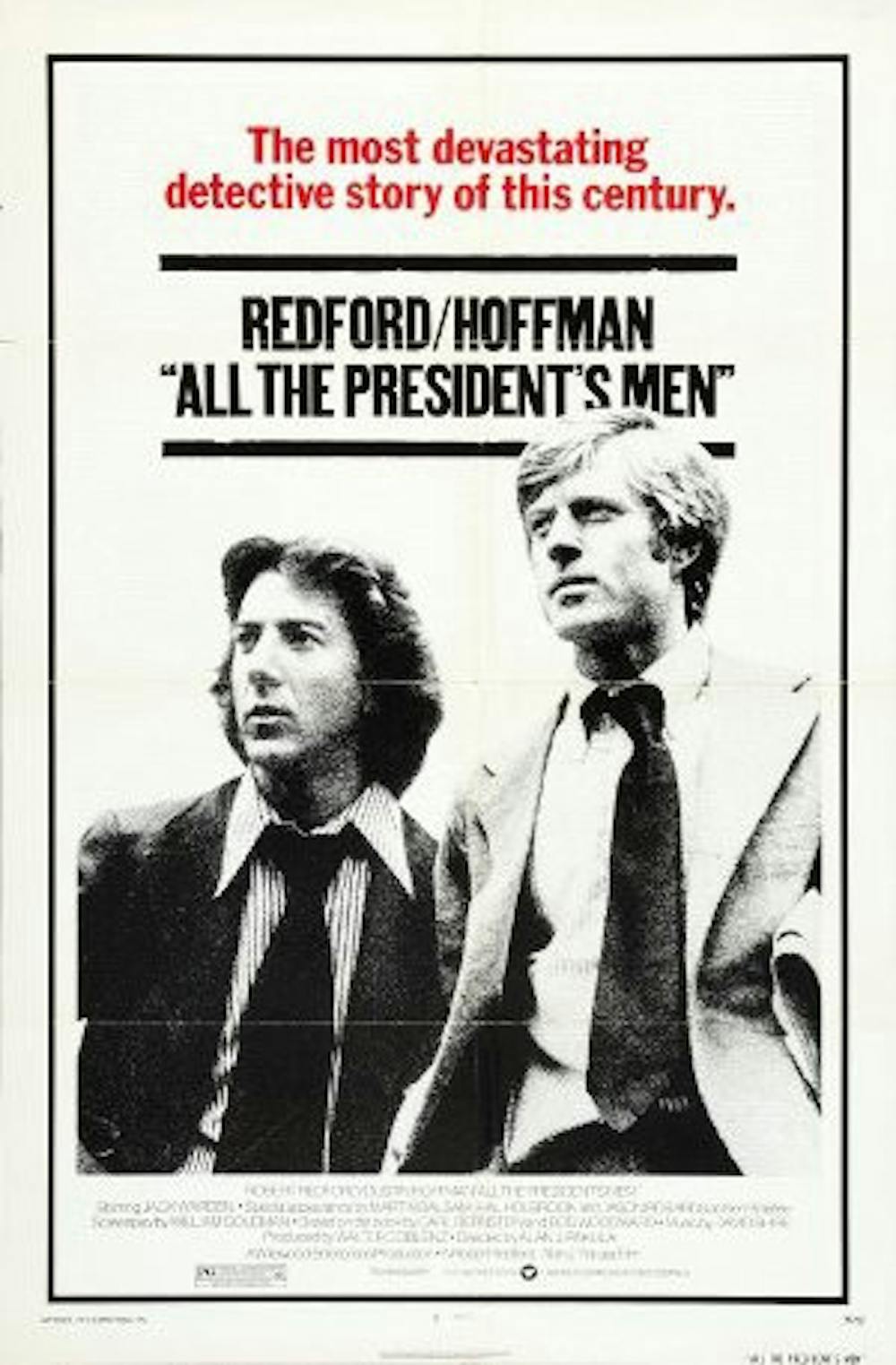

“All the President’s Men”

The true story of The Washington Post reporters who uncovered the Watergate scandal and brought down President Richard Nixon, “All the President’s Men” is a thrilling retelling of one of America’s most infamous political events. Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) track the story. They begin with what appears to be nothing more than a break-in at the Democratic headquarters, and follow it all the way to the highest levels of the government, exposing one of America’s greatest political scandals. The two legendary actors bring the compelling story to life, showing the important role of the free press in holding authority figures accountable.

Though much of the story involves Bernstein and Woodward fruitlessly tracking down obscure leads and connections, “All the President’s Men” is engaging and suspenseful throughout. It has all the makings of a great detective story. As the two reporters get closer to the truth, viewers are on the edge of their seats waiting for the pieces to fall into place and expose the conspiracy. It’s got nail-biting suspense and an empowering message about holding government figures accountable to the citizens they represent — what more could one need for an outstanding political movie?

— Thomas Roades

“La Lengua de las Mariposas”

Also known as its anglicized title “Butterfly,” “La Lengua de las Mariposas” fearlessly depicts how political divisiveness and war corrode society from the top down. The 1999 film is a cinematic adaptation of stories from “¿Qué me quieres, amor?” by Galician author Manuel Rivas, which expose the atrocities associated with the onset of the Spanish Civil War. The trauma of the film is all the more elevated as the narrative is centered around one of society’s most vulnerable members — a child.

Set in Galicia, Spain in 1936, the movie tracks the experiences of a tragically nervous school boy named Moncho (Manuel Lozano) who befriends his modest, inspiring and outwardly anti-nationalist teacher Don Gregorio (Fernando Fernán Gómez). Don Gregorio empowers his students by fueling their curiosity — he introduces them to the natural world and, famously, the extraordinary behavior of butterflies. Just as butterflies disseminate pollen, Don Gregorio hopes to diffuse the seeds of “liberty” by enlightening the next generation of young, curious students.

When nationalist trucks arrive at the film’s end to detain all of Galicia’s known Republicans, Moncho is stunned to watch his kind teacher get whisked away. The film gives voice to the dangers of nationalism and the repression of free speech. Specifically, it reveals the pain associated with having to stifle one’s beliefs for the sake of safety. The balance between the touching teacher-student relationship and the jarring nature of the political content not only make the film digestible but extremely effective in relaying its message. The grating conflict between the two polarized plot components reflects the unapologetically divisive reality of war.

And — just saying — Rotten Tomatoes doesn’t give out 96 percent ratings lightly.

— Caroline Hockenbury

“The Manchurian Candidate” (1962)

A good indicator of a film’s lasting relevance is when it has a remake over four decades later, taking place in a different war and with a different set of characters, but still retaining the essential themes of its original. But this is not a review of the 2004 version — while well-intentioned and mostly well-done, it doesn’t quite pack the punch of its 1962 predecessor.

“The Manchurian Candidate” (1962) set the standard for both the paranoia and the biting satire that would saturate countless political films after it. Its plot is far too complex to accurately describe here, but in short, several American soldiers return home from the Korean War with a little more than the average case of PTSD. It’s revealed early on that Sergeant Raymond Shaw (a chilling Laurence Harvey) has been brainwashed by Communists, is responsible for the murders of fellow American soldiers and will soon be instructed to kill again — unless Captain Bennett Marco (one of Frank Sinatra’s best roles) and Allen Melvin (James Edwards) can put a stop to it.

This is a gross reduction of an endlessly complicated, gripping movie, one that asks uncomfortable but important questions about American identity and patriotism. Over half a century past its initial release, the film still holds incredible and ultimately disturbing political resonance. If “1984” should be required reading for every high school student, then “The Manchurian Candidate” should be required viewing.

— Dan Goff

“Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb”

The best films are the ones that demand multiple revisits. Stanley Kubrick’s satirical masterpiece, “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” is one of them — each rewatch increasingly allows viewers to catch the quickly moving, nearly whiplash-inducing punch lines and subtle, hysterical character quirks they may have missed the first few times around. The film takes place during the height of the Cold War and stars Peter Sellers in three drastically different roles — Lionel Mandrake, a captain who attempts to prevent a nuclear attack on the USSR ordered by an unbalanced general (Sterling Hayden), the perpetually befuddled U.S. President Merkin Muffley and the titular Strangelove, a sinister presidential adviser who evokes Nazi sentiments.

With its heated diplomatic discussions in the War Room and tense B-52 bomber crew flight scenes, the film is shot like an intense, somber political thriller. The self-serious set-up, however, merely becomes a hilarious backdrop for the cast of colorful characters unaware of their own juvenile, ridiculous antics. From the President’s attempt to warn the Soviet premier of the impending nuclear attack to General ‘Buck’ Turgidson (George C. Scott) giddily praising his pilots on their ability to end civilization, the film equips itself with a jingoism that never becomes too absurd, especially given today’s political climate. Kubrick finds hilarity in every possible scenario, making “Dr. Strangelove” not only a brilliant comedy, but a sharp, subversive commentary on Cold War anxieties.

— Darby Delaney