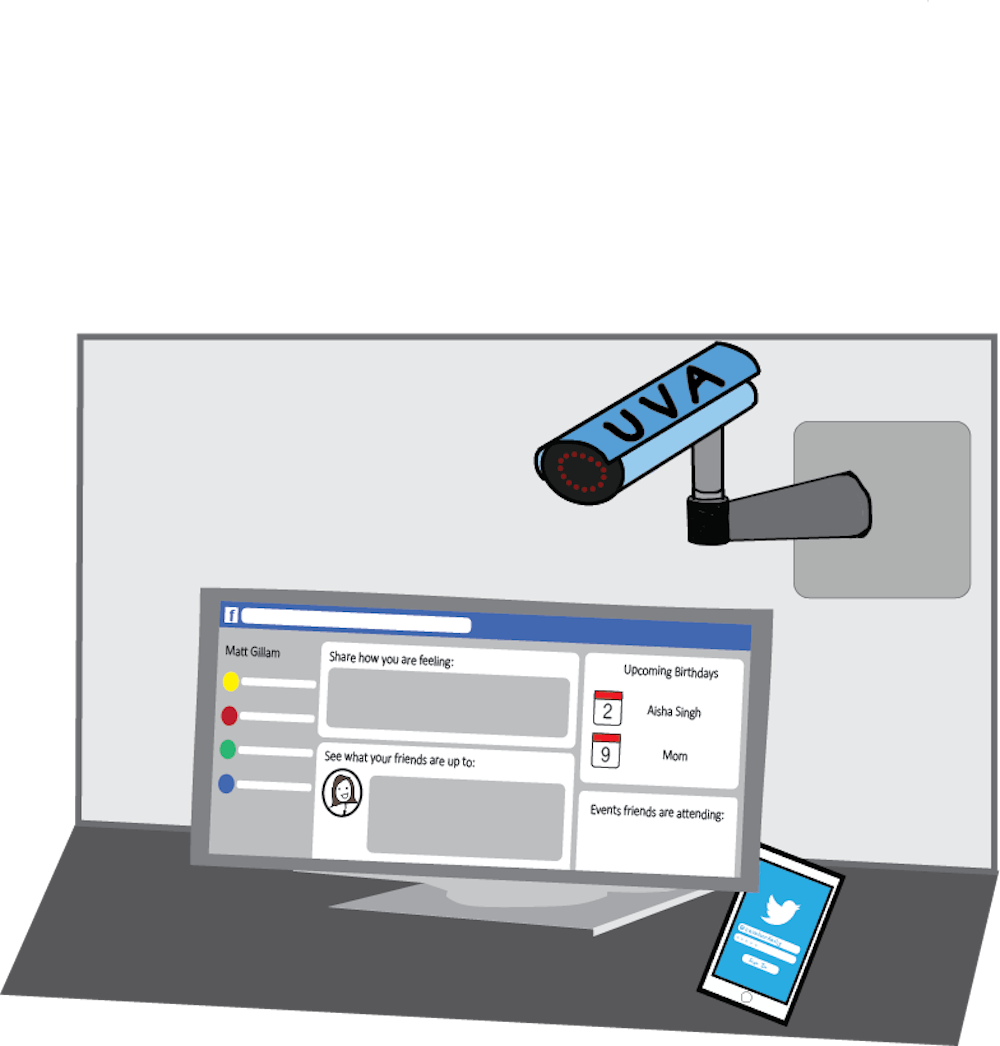

Since last September, the University Police Department has partnered with Social Sentinel, a social media scanning company, in order to identify potential threats to public safety. But some members of the University community are raising concerns about the scanning activities.

The contract with Social Sentinel will cost the University approximately $18,500 annually. This company browses through public social media posts to “identify potential public safety threats and to help provide situational awareness for safety concerns,” said Benjamin Rexrode, University community service and crime prevention coordinate officer, in an email statement.

Rexrode said this social media scanning system is one measure the University is taking to increase safety and prepare for future tragedies on Grounds.

Gary Margolis, founder and CEO of Social Sentinel, said in an email statement that Social Sentinel uses proprietary technology to scan through public posts “through its extensive 450k+ library of harm terms.” Alerts are then sent to their clients about any post containing any harmful language.

Although no official report of the program’s progress has been released, some people within the University have doubts about its efficiency.

“It strikes me as a poor use of University funds, because we can’t know how well it works,” said Siva Vaidhyanathan, a Media Studies professor and director of the Center for Media and Citizenship. “We are never going to get a report on how well it works. We can’t trust them because the algorithm is proprietary and secret, and we can’t know whether it is under-identifying or over-identifying potential threats.”

Vaidhyanathan further mentioned that majority of social media scanning companies tend to utilize geolocation, or the identification of geographic locations of electronic objects such as mobile phones.

“This whole practice is silly,” Vaidhyanathan said. “You have to hope that person has location services on and is willing to share location. You know many people don’t do that, especially those who want to do harm to others … So, there would be many threats not discovered by Social Sentinel.”

Margolis said that Social Sentinel scans posts worldwide without analyzing data based on geolocation. However, a description about how the company specifically scans posts was not clearly stated other than their use of “proprietary advanced technology.” Social media platforms that Social Sentinel scans include Facebook and Twitter.

According to Margolis, Social Sentinel scans through one billion social media posts per day to identify any potential threats by being an “early warning system” and “help before something bad happens.”

Some University faculty believe a warning system is not the solution. Vaidhyanathan mentioned that the University should focus on responding to threats rather than searching for them.

“The problem with Aug. 11 and 12 was that actual human beings watching activity on Discord alerted the University that there was an impending invasion, and the University did not take that seriously,” Vaidhyanathan said. “So, that is just a completely different problem.”

Some other University students and faculty agree that Social Sentinel may not be the may not be the most effective way to identify threats.

Second-year College student Patrick Baratta expressed skepticism towards the monitoring of social media posts.

“I think the logic behind it is to look at this metadata to find out what is going on, but I don’t think social media is the right platform for that,” Baratta said.

Vaidhyanathan shared similar skepticism as Baratta. He said the problem relies on the fact that most radical people do not publicly post their plans or actions on publicly available social media accounts, such as Facebook or Twitter, but rather on private accounts or anonymously on platforms such as Discord, an anonymous gaming platform.These posts can not be scanned or flagged by Social Sentinel.

First-year College student Allison Gottlieb said the monitoring efforts may be a positive step forward.

“This plan, although not executed in the most effective manner, does prove that at least the University is moving in the right direction,” Gottlieb said. “They are taking action, and recognizing that this is a pertinent problem, which must be addressed in order to ensure safety and inclusivity on Grounds and in the Charlottesville area. However, this isn’t the end of the road — it should only be the beginning.”

Additionally, Baratta said he thinks the University should have explicitly sent an email to community members describing what Social Sentinel was planning to do, rather than release the news through the press.

“We get emails when there is a robbery at GrandMarc, even though it might not affect us directly and may make us feel unsafe,” Baratta said. “But if we are not getting an email when we are having our social media looked at by the school, I think it is a little iffy.”

Correction: This article has been updated with additional information from Social Sentinel. It previously inaccurately reported that Social Sentinel scans social media posts based on geographic location, creates Twitter accounts and follows every active Twitter account within a geographic area, however, Social Sentinel has said these are not accurate descriptions of its proprietary technology and that it does not search posts based on geographic location.