Across the country, there has been a recent rise in non-tenure track, or adjunct, faculty. Depending on the university, non-tenure track faculty can either have contracts with substantial employment benefits or just receive an hourly wage.

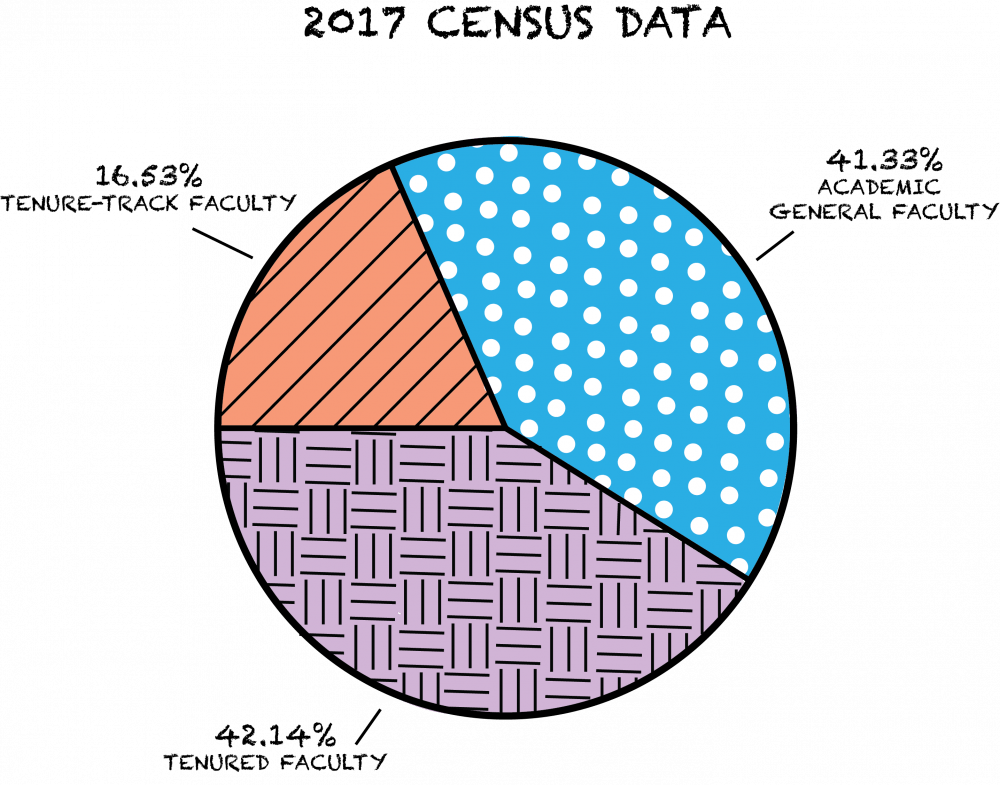

Despite this trend, about 59 percent of University faculty members have received tenure or are currently on the tenure-track, according to 2017 Census data collected by the Office of the Executive Vice President and Provost.

A tenured appointment is “without term,” meaning a faculty member who receives tenure at the University has a contract with no end date. Tenured professors at the University are expected to teach, to conduct research and to give to the University or to the field more generally through service.

Examining the process

The most common steps through the professorial ranks at the University are assistant professor, associate professor and professor. After a faculty member completes their qualifying terminal degree and demonstrates potential as an independent scholar and teacher, they can be elected as a tenure-track assistant professor.

However, receiving tenure does not guarantee that assistant or associate professors will be promoted to full professorship during their time at the University.

Each year, a group of faculty members across schools are recommended to the Board of Visitors for promotion to associate professors with tenure.

If a faculty member applies for tenure and does not receive it, they will have until the end of their contract to look for further employment as they will not be permitted to renew their contract. Despite these high stakes, tenure continues to be sought after by academics for its status and security.

The process varies across schools, but in most cases, it relies on a series of evaluations across the professor’s department and school before University-level assessment.

“It is long and detailed and an extensive amount of review and assessment,” Dean of Engineering Craig Benson said. “It’s rigorous.”

In the McIntire School of Commerce, the tenure process begins with hiring.

Whether the candidates are experienced professors or fresh out of doctorate programs, Carl Zeithaml, dean of the McIntire School of Commerce, said McIntire assesses applicants’ backgrounds and experiences to see if they would fit with the school culture. This includes cooperating with other faculty members, being an outstanding researcher or possessing the potential to be an outstanding teacher.

“If you hire the right people and then invest in them, there shouldn’t be an issue about tenure,” Zeithaml said.

Upon hiring, tenure-track faculty in McIntire go through a strenuous series of annual reviews. Every year, all faculty in McIntire develop an extensive two-year review of everything that they’ve done in terms of teaching, research and service and develop a plan for the following year.

“As a result of that, each faculty member and again, particularly the untenured faculty members, have a very clear idea of where they stand, whether they’re making progress, where they are excelling, and where they are having potentially problems,” Zeithaml said.

Typically, once a faculty member reaches the fall of their sixth year, they are required to submit a mass of historical information for promotion and tenure. Alfred Weaver, professor of computer science and chair of the Faculty Senate, said the combination of working full-time and collecting voluminous amounts of information is stressful. The Faculty Senate represents all faculties of the University in academic affairs and advises the University president and rector of the Board of Visitors on educational affairs affecting the overall well-being of the University.

Weaver said the application requires details like every conference attended, its location and date, and every publication down to the specific issue and page number.

In addition to internal review, the University requires tenure-track professors to be assessed by external reviewers in the faculty member’s field.

Eileen Chou, associate professor of public policy, received tenure in May 2017. Unlike most tenure-track faculty, Chou was asked to apply for tenure early. She said picking the external reviewers was the most stressful part of the tenure process.

“Tenure review is not just about how your colleagues and how your senior colleagues evaluate your work,” Chou said. “It’s also about how these anonymous reviewers in the field see your work.”

Depending on the school, there is a department-level consideration process. This may be a department-level Promotion and Tenure Committee or a department-wide vote by tenured professors. Upon approval, the candidate’s information is sent to the school level.

The school level Promotion and Tenure Committee will make a recommendation to the dean upon reviewing all of the candidate’s materials. The dean of the school will make their formal recommendation to the Provost after the Promotion and Tenure Committee assesses the candidate on a variety of criteria. In the School of Engineering, criteria include things such as scholarly independence and ability to effectively run a graduate program. This process occurs annually with the number of candidates varying each year.

At the Provost’s office, there is a separate Promotion and Tenure Committee made up of tenured, full professors from across the University. Kerry Abrams, vice provost for Faculty Affairs and chair of the committee, said the main purpose of this step is to ensure fairness and objectivity in the process at the department and school levels.

“I’m unlikely to know with a microbiologist or an astronomer or a German literature scholar whether the external reviewers are right or not . . . but I can tell and our committee can tell, whether the external letter reviewers said one thing and the faculty’s ignoring it,” Abrams said.

This committee makes a recommendation to the Provost, and the Provost makes a final recommendation to the Board of Visitors.

Although it is not common, Abrams said the Provost can and does occasionally reject tenure applicants at the University level.

Abrams does not know of a case where the Board of Visitors has rejected a Provost’s recommendation for tenure.

Behind the non-tenure track

Forty-one percent of University faculty are Academic General Faculty, a collection of part-time and full-time employees who may be contracted annually or for multiple years depending on the school and past history of the employee. Academic General Faculty can be hired to teach, research, provide clinical service or incorporate their prior work experience into teaching or research.

The Provost’s Office created a new policy in January 2017 requiring Academic General Faculty to be eligible for promotion over time. The policy also required three-year contracts after three years of working at the University. Abrams, who spearheaded this effort, said the new policy aims to increase stability and reduce churn.

“We want the Academic General Faculty to also feel like they’re a part of the faculty and that they can make a career for themselves here,” Abrams said.

These faculty members have contracts, receive health benefits and can even rise to the level of full professor all without tenure. According to the 2017 Census, approximately 10 percent of part-time and full-time Academic General Faculty at the University have the title of full professor.

William Shobe, professor of public policy and director of the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, joined the University as an Academic General Faculty member in 2004. Prior to his time in academia, Shobe headed the division of Economic and Regulatory Analysis at the Virginia Department of Planning and Budget. Shobe said in his experience there has not been much difference between the tenure-track and non-tenure-track status.

“I have been involved in academic research, teaching, University governance and all the rest,” Shobe said in an email to The Cavalier Daily. “I have had a chance to do some very meaningful work both before and after coming to the University.”

Shobe said the main downside to being an Academic General Faculty member is not having the academic status tenure provides.

“Achieving tenure at a university like U.Va. is [a] hard-earned honor that reflects a high level of academic achievement and earns the recipient a role in university governance that is not generally accorded to non-tenured faculty,” Shobe said.

Some professors have expressed concern over the rise in non-tenured track faculty at large. Weaver said increasing non-tenure track faculty leads to more churn in departments and schools.

“If you go to the trouble of building a relationship with a person, and you’re writing papers together and you’re doing joint research and you’re getting joint grants, but that person then gets a better job offer and goes away, that’s not good for anybody,” Weaver said.

However, Abrams said there is only slightly more turnover among Academic General Faculty than tenured positions.

The bottom line

Despite the increased opportunities offered to the Academic General Faculty, the majority of professors at the University are tenure-track or tenured. Tenured faculty have more job security and more flexibility on a daily basis regarding teaching, research and service.

Chou said tenure allows a professor to explore larger questions that may take years of research to complete — something the job security of tenure provides.

“With tenure you get to do these big projects, you get to shoot for the moon, you get to make greater theoretical contributions that might be really risky and might not be something you want to do before you get tenure,” Chou said.

In the University’s efforts to build a staff, tenure is still a significant factor in recruiting and maintaining the most qualified faculty possible.

“We believe the most important thing that we can do is to recruit, retain and develop the very best faculty because they’re going to be the ones who have the greatest, most positive impact on our students,” Zeithaml said. “They’re going to be the ones that advance knowledge in their disciplines through their research, and they’re going to be the best people to create a culture of service and commitment to both the school and the University.”