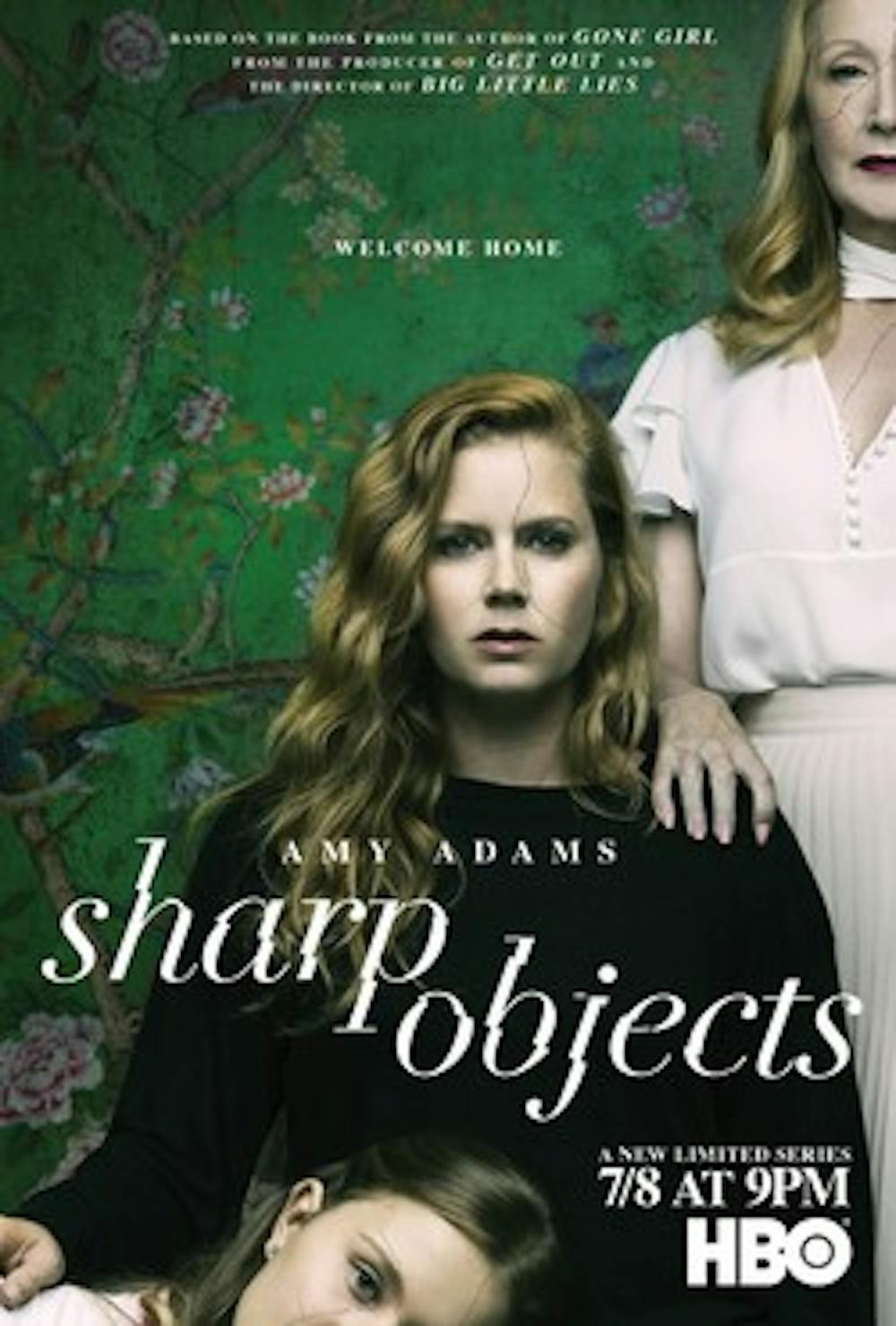

One wouldn’t be blamed for being out of the loop on HBO’s recent summer drama, “Sharp Objects.” While it is not exactly one of the network’s “Game of Thrones”-level mainstream sensations, it has garnered critical praise for its feminist themes and strong performances from lead actresses Amy Adams, Eliza Scanlen and Patricia Clarkson. Yet it also merits viewing in today’s sometimes backwards-seeming world — and specifically the community of embedded and complicated history at U.Va. — for its artful integration of past horrors with present experience.

“Sharp Objects” is adapted from the original novel by Gillian Flynn, who wrote the also-adapted “Gone Girl.” This adaptation is directed by Jean Marc-Vallee, who is no stranger to stories about women dealing with past trauma, having directed the domestic abuse drama “Big Little Lies” for HBO and feminist adventure film “Wild” beforehand. Initially, it is a slow and dark procedural featuring journalist Camille Preaker (Amy Adams) returning to her small Southern Missouri town, known as Wind Gap, to report on the recent murder of two girls.

But through its eight episodes, the emerging and far more intriguing narrative is not a murder mystery, but the family drama surrounding Camille and her family. Camille’s clan consists of her cold and attention-loving mother Adora (Patricia Clarkson), doll-like by day and party-animal by night sister Amma (Elizabeth Scanlan) and detached, practically lethargic stepfather Alan (Henry Czerny). There is also the unseen and largely unspoken of presence of Camille’s mysterious biological father, who overshadows her entire identity within Wind Gap. The absence of any patriarchal figure leaves her family female-dominated, and the battle-lines across all these members of common gender are drawn based on their respective generations.

Without getting into spoiler territory, “Sharp Objects” murder mystery and surrounding events end up being very concerned with the social dynamics of age. Wind Gap draws socially-acceptable melancholy from the death of two little girls. The teenage brother of one of the girls, John Keene, is seen as behaving irregularly from his gender and age when he publically cries for his lost sister. Heavy gossip circulates in tea parties consisting of Wind Gap’s older and wealthier women including Camille’s mother and aunt. Camille is a black sheep for being a career woman who moved on to the “big city,” unlike her middle-age peers now living in domestic roles and traditional marriages.

All of these age groups are haunted to various degrees by their past. John Keene regrets his family moving to Wind Gap and how excluded he and his sister felt ever since. Adora leaves an empty room in the family house reserved for Marian, a child sister of Camille’s who tragically passed from an unknown disease. Camille and her entire cheer team were ritually sexually assaulted in the woods by the high school football team. Many have since dismissed such trauma as normal occurrences, just the way things are in a small Southern town. Not everyone can move on so easily.

For Camille, these moments of trauma are not relegated to idle memory. They exist in the present. Beautiful editing and effects seamlessly integrate Camille’s child-self and her sister Marian into events, seen lurking like ghosts in reflections and empty stairways. As a coping mechanism for her scarred childhood, Camille engages in self-harm and marks her body with scratches spelling out evocative words from her childhood, “Ripe,” “Milk,” “Cherry” and “Dirt”. Her body is a literal map of her past. In one particularly memorable scene from the opening, her younger self actually pricks her to wake her up. Sophia Lillis convincingly plays a younger version of Amy Adams’ character, and her appearances make for the artful television equivalent of a literary, internal monologue.

In “Sharp Objects,” the past has character. It is alive. This turns out to have significant impact on the story — staying spoiler free — and ultimately define the resolution of both the murder mystery and Camille’s role in her family. The past also lives in Wind Gap’s connection to the Confederacy, a heritage it celebrates in a holiday known as “Calhoun Day” where the myth of a pregnant woman who chose rape by Union soldiers over betraying Confederate secrets is celebrated with costumes and plentiful drinking. Every person and every place has a history. Oftentimes it will be an ugly one. In forcing its characters to confront the past, “Sharp Objects” makes compelling television which reaches across time and age.

Here in Charlottesville, the past also lives on to haunt residents and students alike. The University was built with slave labor in Jefferson’s time. It is an environment where the past, for both the beauty seen in libraries full of eclectic knowledge, and the horror in bricks laid by enslaved laborers, is very much present. A painful and repressed history is finally being lent credence through University efforts, including building the memorial to enslaved laborers. Last year the ugly past came knocking at the door when Nazis wore badges of “Confederate heritage” as an excuse to spread hate and violence. We are still very much living with history. Or, as the journalist Eduardo Galeano said,“History never really says goodbye.”