Reconciling an institution’s past controversies with the comparatively liberal present is a challenge that often surfaces when assessing its favorite historical figures. The University faces this challenge directly when addressing the legacy of its first president, Edwin Alderman. Though Alderman is notable for his leadership and contributions to the University community, an increased awareness of Alderman’s involvement with eugenics and ties to white supremacy has begun to overshadow his integral role in the University’s development, and complicates the community’s task of coming to terms with its history.

The University’s inaugural president

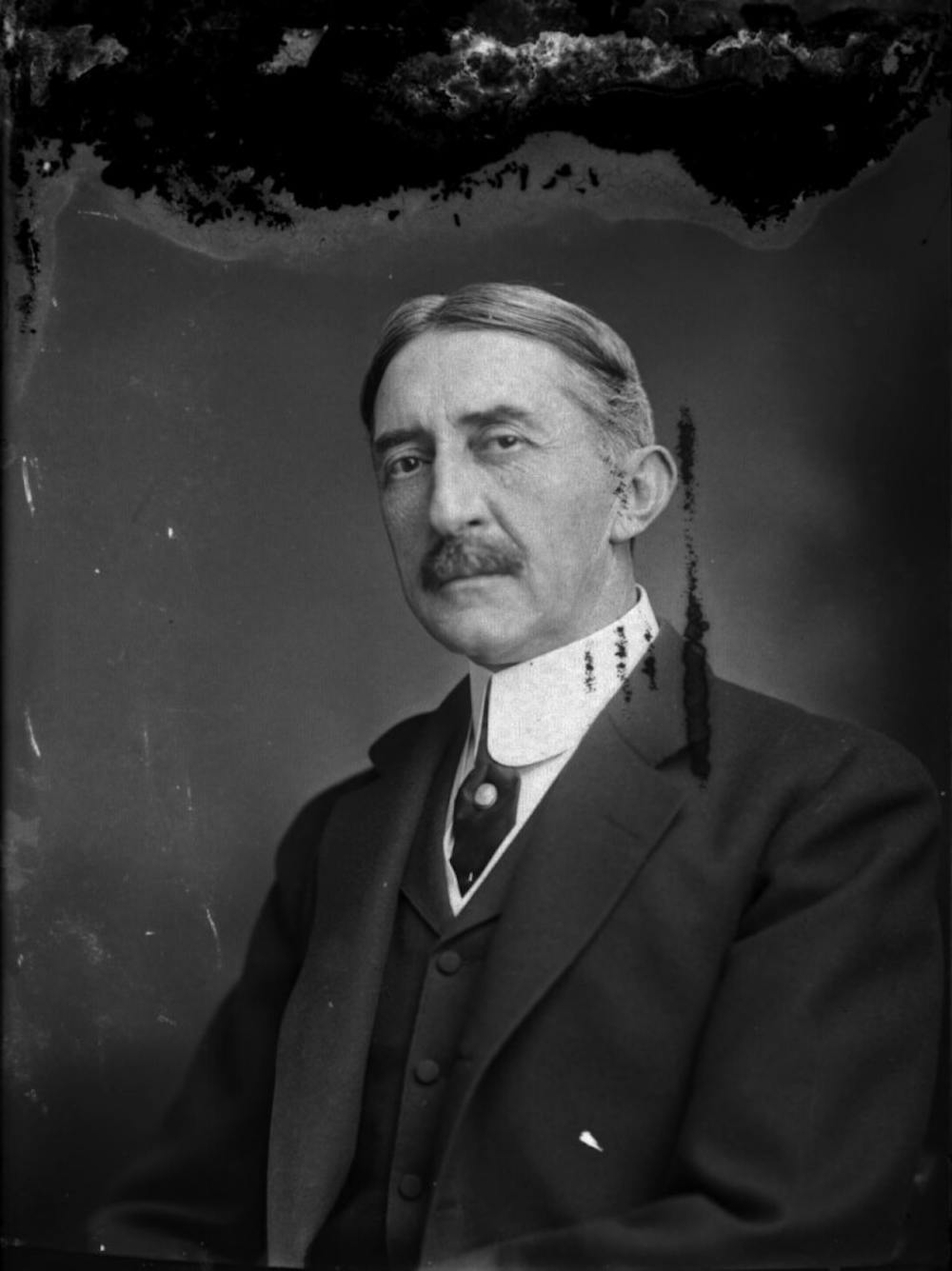

Edwin Anderson Alderman served as the University of Virginia’s first president from 1904 until his death in 1931. The Board of Visitors had previously governed the University. During his tenure at Virginia, Alderman founded the Curry Memorial School of Education in 1905, sanctioned the admission of women to U.Va.’s graduate and professional programs as early as 1918, reorganized the University to increase its efficiency and multiplied its endowment by a factor of nearly 30.

“Alderman’s principal legacy was to establish a firmer and more flexible administrative structure, one that was suitable to the growth of the institution,” said Margaret O’Bryant, an Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society librarian. “The University was growing and was facing serious issues with expansion and renovation after the Rotunda fire, and the administrative structure was no longer suitable.”

Many credit the University’s subsequent era of “Southern Progressivism” and academic renown to these administrative innovations.

According to Assist. History Prof. Sarah Milov, Alderman led the University into the 20th century intent to develop a modernized institution. The President’s definition of “modernization,” which focused on academic research, was inextricably linked with white supremacy, Milov said.

“The word ‘modernization’ in the early twentieth-century South, but also in the North, frequently went hand-in-hand with racial theory,” Milov said. “For him [Alderman], a commitment to white supremacy and a commitment to education were one in the same: it was a way to make the South a better place, and he was concerned foremost with modernizing the University of Virginia.”

Today, one of the most prominent libraries on Grounds bears Alderman’s name.

Ties to eugenics and white supremacy

Alderman’s presidency is also marked by his support of eugenics, the pseudoscience of “improving” the human population by manipulating reproduction. When applied in the political arena, eugenics provided “false scientific justification for institutionalizing racisms,” in the words of Lyndsey Muehling, an Immunology doctoral candidate and outreach organizer for the scientific literacy non-profit Cville Comm-UNI-ty. Compulsory sterilization laws, such as the Eugenical Sterilization Act of 1924, were among the legislation that resulted from eugenics research at U.Va.

Alderman’s ties to eugenics in part legitimized the practice as a cornerstone of Southern social policy, and played a role in launching U.Va.’s medical program to the position of national repute which it enjoys today, according to Class of 2000 University graduate Gregory Michael Dorr’s dissertation for the American History program “Segregation’s Science: Eugenics and Society in Virginia.” Alderman’s efforts in part prevented the Medical School from being consolidated with a Richmond institution in 1922.

Alderman endorsed eugenics both personally and professionally. He himself served on the National Committee for Mental Hygiene and the Aristogenic Association. According to fourth-year College student Sarah Ashman, who is an American Studies major concentrating in Southern Studies, Alderman created a “network” of eugenicists at U.Va. — including Harvey Jordan, Harry Heck and Ivey Foreman Lewis — who then disseminated their ideologies across disciplines to innumerable students and Virginians.

“We as a research university were producing the work that would then be used by politicians to make that sort of [eugenic] policy reasonable and legal,” Ashman said.

Alderman’s network of eugenicists at the University educated many of the politicians and physicians who later produced and enacted racialist policy in Virginia.

“While it is impossible to know the precise number of University-of-Virginia-trained physicians who performed these [sterilization] operations, it is certain that Virginia alumni performed many of Virginia’s compulsory sterilizations between 1927 and 1972,” Dorr wrote.

Three such Virginia alumni created and executed the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, which followed 600 black men — 399 infected with syphilis and 201 not infected — to study the disease’s effects over 40 years. The experiment was deemed unethical and exploitative because its subjects were not informed of its extent and those infected were not given treatment, even when penicillin was found to be a cure.

Alderman also engaged with the Ku Klux Klan in 1921, accepting a donation of $1,000 — a present-day value of $12,500 — to the University, which he acknowledged in a letter signed “faithfully yours.” In September 2017, former University President Teresa Sullivan announced U.Va. would donate this value to the Charlottesville Patients Fund for the victims of the white supremacist rallies of Aug. 11 and 12, 2017.

Alderman later delivered the acceptance speech for the Lee Statue at Market Street Park — formerly Lee Park — in 1924 on behalf of the City of Charlottesville. General Robert E. Lee’s three-year-old great-granddaughter Mary Walker Lee unveiled the statue, which was shrouded in a Confederate flag.

Alderman’s legacy in the 21st century

In light of U.Va.’s tumultuous past decade, some are calling for a reexamination of President Alderman’s contributions to University history.

Some believe that rededicating Alderman’s namesake library is the most appropriate way to reckon with University history. Charlene Green, Manager of Charlottesville’s Office of Human Rights, encourages an open conversation within the University community, regardless of the library’s fate.

“It’s not fair to have a blanket response — we need to talk about it,” Green said. “There are implications for keeping [Alderman’s name] there, and there are implications for removing it. When you start doing things like that, you set a precedent. Dialogue about the information is critical.”

It’s the prospect of a dialogue across Grounds that appeals to Ashman.

“I would support a conversation about our history in eugenics and the detrimental effects that study had in hopes that it would inspire us in ethical scientific behavior,” Ashman said. “I don’t think that most people are thinking of who Alderman was when they look at the library, but they could be thinking of who someone was. If we’re not going to talk about Alderman, perhaps we could rename the space after someone we would want to talk about, or someone we would want to be inspired by.”

Ashman proposed Elizabeth Tompkins, U.Va.’s first female law school graduate, or one of the individuals who first integrated the University as possible contenders for what is now Alderman Library. She is not alone in suggesting a new name on the library.

“There are many more alumni and people associated with U.Va. that I think are deserving of having their name on the library, but that crusade, or campaign, should be led by students making their own demands,” Milov said.

A campaign for the renaming of spaces honoring eugenicists has already begun on Grounds with Cville Comm-UNI-ty. Lyndsey Muehling reported that the organization is writing an open letter and corresponding petition to the University, advocating for the renaming of Barringer Wing at the U.Va. Health System on account of its namesake’s career in eugenics. The wing is named for Paul Brandon Barringer, chairman of faculty at the University from 1895 to 1903. However, Muehling said that rededicating a University structure named after Alderman may not be a viable undertaking at this time.

“We have discussed Alderman, but Barringer is an easier first step on the list of names we want to see changed,” Muehling said. “Alderman is too much of an institution.”

Though Alderman Library’s renaming may be unlikely by some accounts, it would not be unprecedented. Yale University removed John C. Calhoun’s name from one of its undergraduate residential colleges in 2017. Georgetown University was successful with similar efforts in 2015, though Princeton University’s attempts to rename the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs were unsuccessful in 2016.

The University engaged renamings of its own in 2016, renaming the Medical School’s Jordan Hall, named for University eugenicist Harvey Jordan, as Pinn Hall for Vivian Pinn, the only female, African-American student to graduate from the medical school in 1967. In 2017, the BOV voted to rename International Residential College’s Lewis House, which had been named for University biology professor and eugenicist Ivey Foreman Lewis, as Yen House, honoring W.W. Yen, the first international student to earn a bachelor of arts from the University and the first student from China to graduate in 1900.

There have been no extensive efforts to remove Alderman’s name from University structures.

The difficult balance between a historical figure’s contributions and their controversies has also been a subject of debate when addressing the legacy of U.Va.’s founder. Particularly after the events of August 2017, many have turned to Thomas Jefferson with renewed scrutiny. Though Jefferson may be one of the more acclaimed individuals in a nexus of controversial U.Va. figures, his status as a slaveholder and the publication of his white supremacist ideologies have made his role in the University’s history a point of contention. In response to the events of August 2017, a group of protestors shrouded the Jefferson statue in front of the Rotunda last September.

Nevertheless, some hope to see Alderman’s name remain on the library for reasons ranging from appreciation for his contributions, to a hope for sustained dialogue about his complete history.

“I would not be in favor of renaming things that have been named for him because of his contributions to the University,” O’Bryant said. “Anyone who has made considerable, positive contributions to their environment and life in their community can and should be remembered for the positive things they've done.”

Second-Year Engineering student William Tonks also said Alderman’s name should remain on the library, if only to heighten awareness of the president’s complete history.

“If in 50 years people are still talking about how awful eugenics is because Alderman Library is named ‘Alderman,’ I think that’s a win,” Tonks said.

Regardless of the ultimate name on Alderman Library, many conclude that University students on Grounds are ready for a conversation about reexamining old wounds in its history.

“Students are emboldened right now,” Milov said. “And it’s amazing to watch.”