Meaghan O’Reilly carries pepper spray in her backpack. After two attempted abductions were reported off-Grounds last October, O’Reilly — now a third-year College student — decided it was time to stock up.

Still, O’Reilly said, the inconvenience of finding safe ways to go to the library and return home meant she would stay in her apartment instead of going to the library.

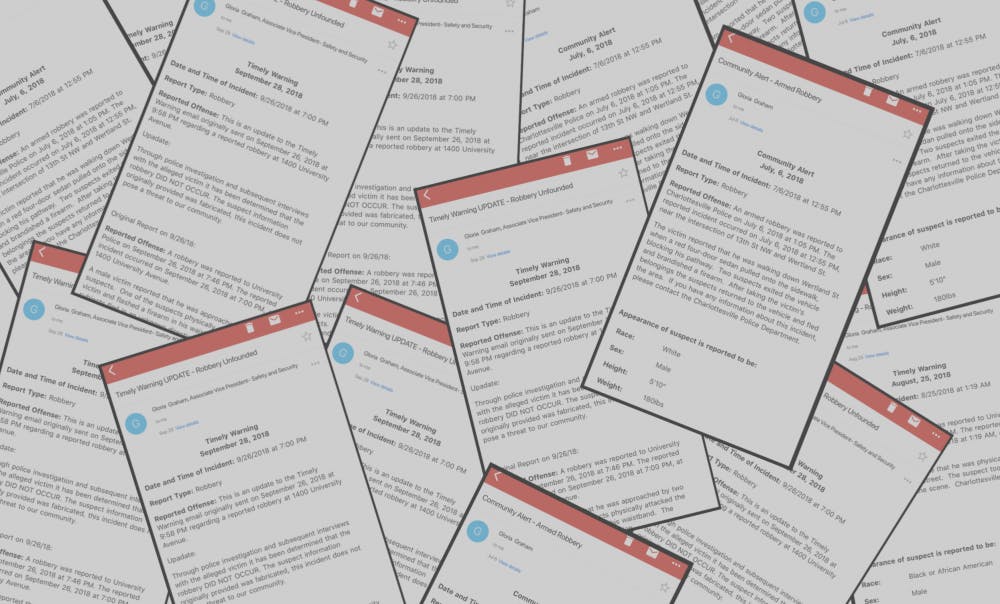

The University issued alerts to the University community for both attempted abductions, as well as several other incidents that fall. For some incidents, the University issued timely warnings — notifications for tightly-defined incidents and crimes — and for the rest, community alerts.

But after recent off-Grounds crimes did not result in the issuance of timely warnings or community alerts, some students are asking what warrants a notification to the University community in the first place.

Now, as the University gears up to release new safety application LiveSafe, the Office of Safety and Emergency Preparedness and University Police Department are doubling down on efforts to update the community on reported incidents.

Timely warnings, community alerts and the Clery Act

In January 2018, a man displayed a firearm when denied entry into Boylan Heights. The University did not issue a timely warning or community alert, citing the Clery Act.

The Clery Act — a federal law enacted in 1990 that requires universities to disclose information about crime on and near campus — dictates where and in which cases the University can issue timely warnings for incidents on- and off-Grounds.

The University will only issue a timely warning if a Clery Act crime has been committed in a Clery reportable location, if there is a serious or ongoing threat to the community and if the suspect has not been apprehended. All of the criteria have to be met in order for the law to take effect and require the University to issue a timely warning, which usually consists of information about the suspect, the type of threat, and the date, time and location of the incident.

Clery-reportable locations include Grounds and public property within or near Grounds. The Clery Act also covers fraternity and sorority houses and off-Grounds locations that are owned, controlled or leased by the University, frequented by students and used towards education.

Clery Act crimes include homicide, sex offenses, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, arson, hate crimes, dating violence, domestic violence, stalking and arrests and referrals for disciplinary action for liquor law violations, drug law violations and carrying or possessing illegal weapons.

If an incident constitutes a serious or ongoing threat to the community, but did not occur in a Clery-reportable location or was not a Clery Act crime, the University can issue a community alert — generally similar in content to a timely warning — but is not required to do so. Most recently, the University issued a community alert for a series of pick-pocketing incidents at an establishment on the Corner.

At a meeting a few days after the Boylan Heights incident, Student Council addressed student concerns regarding why the University did not issue a timely warning or community alert.

As the incident did not occur in a Clery-reportable location, it was not eligible for a timely warning consideration. Furthermore, the University said it did not meet the community alert criteria that an incident must pose “a serious or ongoing threat” to the community.

“Given the quick law enforcement response, and as there was no ongoing threat to public safety, a community alert was not issued,” University spokesperson Anthony de Bruyn said in an email statement to The Cavalier Daily following the incident.

Lukas Pietrzak — at the time a third-year College student and Student Council representative — expressed concern with calling the incident “cleared” at a Student Council meeting. The suspect left the scene before police arrived.

In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Pietrzak — now a fourth-year and in his second term as a Student Council representative — said the Boylan incident marked a moment when students thought University alerts had failed.

“Obviously, the University told us … that if it’s off-Grounds, if it’s not an imminent threat to the University, they aren’t allowed to send out these Clery Act alerts,” Pietrzak said. “I, along, with other reps expressed that that’s a poor excuse, and something for the University to just fall back on.”

Pietrzak said he and others believes the Clery geography is currently too limited, making it more difficult for the University to send timely warnings.

“If we could change federal law to make it easier for the University to send alerts, I would say that is the answer in a heartbeat,” Pietrzak said. “But obviously we know the political situation is a lot more complicated than that.”

Student frustrations with not receiving alerts

This year, on the night of the Wertland Street Block Party, third-year College student Cayden Dalton was arrested for strangulation, assault and abduction, and incarcerated until a hearing Oct. 11.

Because the incident did not pose an ongoing threat to the community, the University did not issue a timely warning or community alert.

In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, University Police Chief Tommye Sutton — who started as chief Aug. 1 — added that the point of alerts is to keep students safe, not to let them know the existence of every incident that occurs.

“If there’s no danger to the community or if the situation has been resolved — with the identity or the arrest of an individual — there’s no update emergency alert to send for an individual who has been identified and there’s no longer a threat,” Sutton said.

But third-year Commerce student Vaibhav Mehta expressed frustration that students were not made aware of the Dalton incident.

“We’re paying a lot of money to go to school here, and part of that money goes to safety,” Mehta said. “So if there’s a threat to a student’s safety like myself, because someone’s being strangled, even if they’re being apprehended, it’s important to know that this kind of thing happens at a respected university.”

For incidents for which alerts have been issued, O’Reilly said she wished the University sent more updates after the situations have been resolved.

The University has sent two updates to community alerts and timely warnings this semester. On Sept. 20 — following the issuance of a community alert for robbery and sexual assault the previous evening — the University sent an update that the suspect was in custody. On Sept. 28, the University sent an update to a prior timely warning, saying the reporter, who claimed he had been robbed by two black men, had fabricated the accusation.

Sutton said sending out updates is a new priority of the University Police Department.

“We recognize [sending updates] to have been a challenge of ours,” Sutton said. “[The robbery alert] was followed up by a resolution. That is our plan to be a common practice going forward of making sure we give that resolution to the community via updates.”

LiveSafe and the future of U.Va. alerts

New technology may be the solution to students’ concerns about not receiving alerts. Pietrzak said the Safety and Wellness Committee of Student Council has been working with the administration to launch the LiveSafe application.

The University decided to adopt the application after students expressed concerns about emergency preparedness following the events of Aug. 11 and 12.

LiveSafe is a mobile emergency alert system that allows students, faculty and staff to report suspicious behavior and safety hazards on- and off-Grounds. The application sends out geographically-targeted alerts to users in affected locations.

Sutton said his team has been researching tools to help keep the community apprised of safety concerns and non-traditional platforms through which the community can communicate with safety officials. LiveSafe, Sutton said, is one of these platforms.

“We live in a very active society, so we want to make sure we avail ourselves to individuals to communicate with us in the way they are most comfortable,” Sutton said.

Gloria Graham, associate vice president for safety and security, said in an email to The Cavalier Daily that University-specific features are being configured for the application, which is used at many different universities including Virginia Tech and James Madison University.

These features include the ability to report non-emergencies to University police and communicate via text with police, anonymously if desired. Additionally, individuals can submit photographs and videos along with their tips, use Safe-Walk features — allowing a student to alert specific phone contact when they have arrived at a location safely — and receive geographically-specific alerts.

Another institution, Graham said, used the geographically-specific notifications to alert library patrons of any recent thefts in the library as they enter the building.

Graham said the application, which will cost the University $42,000 annually, will undergo a soft-launch in January 2019 before its community-wide release in June. The purpose of the soft-launch, Graham said, is to test the application through different scenarios.

In the meantime, Pietrzak said he encourages students to pay attention to Student Council and application launch steps.

“If the University’s going to continue to hide behind the Clery Act for why they can’t send out more alerts, this shows student self-governance stepping up and taking action to protect each other,” Pietrzak said.