In the wake of the inauguration of President Jim Ryan, a surge of questions regarding the future of the University arose — particularly how that future relates to reconciling with the University’s past. In his inaugural address Oct. 19, Ryan expressed the need for “an honest assessment of the past and the present, because this is the only way to measure progress.”

Ryan said that the University has made strides to confront issues of economic and racial injustice since its establishment in 1819. Today, the majority of University students are women, over 400 first-year students are first generation and the newest class is the most diverse in University history. However, according to the Living Wage Campaign at UVA, the University still has a long way to go.

The campaign, founded in 1998, is an on-Grounds activist organization with the stated mission to secure job security, safe working conditions and a living wage — an income that ensures a satisfactory standard of living and maintains an individual or family above the federal poverty level — indexed to the cost of living for all employees at the University.

“The University of Virginia continues to support certain hierarchies of power, privilege, and prejudice,” the campaign wrote in “Keeping Our Promises,” its working document. “Women and people of color continue to receive lower wages, and they bear a disproportionate burden of the poverty and marginalization in Charlottesville and in American society at large.”

Why wages are relevant

The deadly Unite the Right Rally in August 2017 — which drew hundreds of white nationalists and counter-demonstrators to Charlottesville — brought renewed scrutiny to the University’s history in regard to white supremacy and slavery as well as to the structural inequity that many say persists within the University and the City of Charlottesville.

“When you think about it, students at this University are being served by a predominantly black working class workforce, immigrants, people of color, and they are being paid poverty wages,” said Hannah Russell-Hunter, a third-year College student and Living Wage activist. “They cannot afford to live in Charlottesville.”

Currently, the University pays workers a minimum wage of $12.38, while Aramark, the provider for University dining services, pays employees $10.65. Meanwhile, according to a MIT’s living wage calculator — which estimates the living wage needed to support individuals and families based on the cost of basic necessities — a living wage in the City stands at $12.02 for a single adult or $16.95 for a family of four in which both parents work.

These calculations do not, however, consider health insurance, vision coverage, dental insurance, disability benefits and access to retirement plans received by University employees — benefits that the University does not offer to contracted employees. However, according to Aramark — the externally-contracted provider for University dining services — the company provides workers with medical and financial benefits as well as development and training opportunities.

James B. Murray Jr., vice rector of the Board of Visitors and chair of the Finance Committee, said it may be “intellectually lazy” to disregard these benefits when calculating University wages.

“Right now our lowest paid employee, compared to the marketplace, is making over 16 dollars if you consider benefits — almost 17 dollars an hour,” Murray said. “In addition to a cash wage, our employees are getting health insurance and retirement benefits that are unavailable from any other employer in the quality and quantity that U.Va. offers them.”

English Prof. Susan Fraiman, founding member of the Living Wage Campaign, pointed out that benefits do not cover basic necessities like food, rent, clothing, childcare or transportation. She further explained that two basic issues perpetuate inequity in the City — substandard wages and a lack of affordable housing. Since 2011, rents have increased 42 percent — from $931 per month for a two-bedroom apartment to $1,325 per month — an upward trend not matched by a rise in wages.

Within the City, 25.9 percent of residents live below the federal poverty level — a measure of income determined by the Department of Health and Human Services that establishes eligibility for government programs and benefits — despite the City’s contrastingly low unemployment rate of 2.7 percent, according to Data USA. Currently, the federal poverty level is $12,140 for an individual and $25,100 for a family of four.

Laura Goldblatt, a postdoctoral fellow at the University and member of the Living Wage Campaign, said that the University — as the largest employer in the City — is in a unique position to directly acknowledge its effect on Charlottesville residents’ standard of living by setting the standard for wages in the region.

“If U.Va. [raises wages], then other people will try to compete, so they’ll raise their wages as well,” Goldblatt said. “The University has an opportunity to yield a lot of influence, which is also an area where questions of poverty and privilege are really dire.”

Administrative responses over the decades

This discord of opinion between University administration and living wage activists is not a new development — 20 years after its 1998 inception, Living Wage Campaign representatives Russell-Hunter and third-year College student Ariana Delaurentis said their organization stands as the longest-running unsuccessful wage campaign at a collegiate institution. Successful living wage campaigns include those at Harvard University and Georgetown University — which achieved their goals in 2016 and 2005, respectively.

However, the Living Wage Campaign at UVA has not been without its successes.

Although the first calls for a living wage emerged after the the University desegregated in the 1960s, Fraiman said the Living Wage movement officially launched on April 15 of 1998 following a teach-in with Labor Movement, a practical forum of professors and activists that initiated a conversation about wages on Grounds. Soon after, the group’s formation followed action on behalf of the City — in 2000, after meeting with the Living Wage Campaign, the Charlottesville City Council voted to pass a living wage ordinance. The ordinance effectively raised base wages to $8 for full-time and part-time City employees at the time.

“There were, at the time, debates about the legality of doing that, but Charlottesville went ahead,” Fraiman said. “A key thing that they did was that they included contracted workers — people who don’t work directly for the city but who work for companies contracted by the city would also have to be paid a living wage.”

During the summer succeeding the City’s decision to raise wages, the University hiked its base wage to $8.19 — a development that Goldblatt and Fraiman see as no coincidence after a period of intense lobbying and campaigning from the Living Wage Campaign.

Further success followed the campaign’s sit-in in April 2006 during which 16 student members and one former faculty member, Anthropology Prof. Wende Marshall, occupied the lobby of Madison Hall for four days and three nights — prompting former University President John T. Casteen III to order the arrest of all 17 protestors on trespassing charges. Marshall was arrested three days prior to the 16 student protestors. That following November, the University raised its starting wage from $9.37 to $9.75.

“[The sit-in] did, obviously, raise consciousness — calling attention to the issue,” Fraiman said. “What do you know, after that, there was another bump in staff starting wages.”

The pattern of University action on wages subsequent to well-publicized campaign efforts continued into 2012. In February 2012, student members enumerated their demands, such as implementing a wage of $11.44, guaranteeing humane working conditions and initiating a Living Wage Oversight Board, in a petition — gathering the signatures of 325 faculty members before delivering the document to former University President Teresa Sullivan.

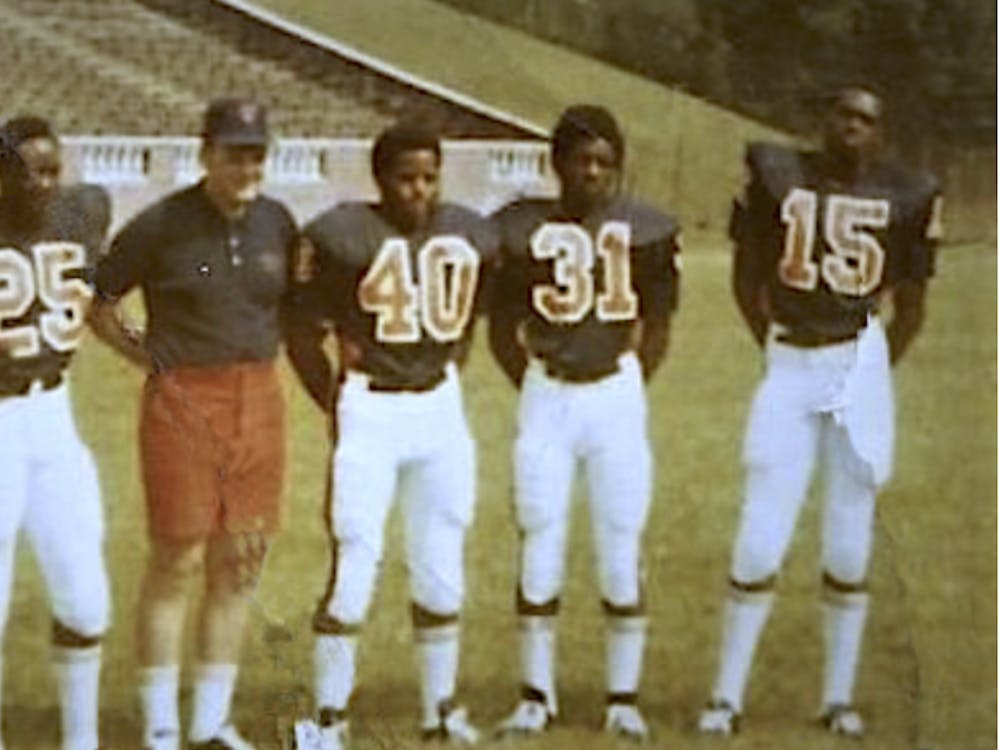

In response, Sullivan penned an open letter to the student body expressing her support for raising wages for the University’s lowest paid workers with one complication — she did not agree with the students’ presented demands. In the days following the publication of Sullivan’s response, 19 activists — including one football player, Wonman Joseph Williams — embarked on what would become a nationally-recognized 12-day hunger strike, pledging to fast until the University met their demands.

That following May, the Board of Visitors voted to bump up the starting hourly wage for University employees from $10.65 an hour to $11.30 an hour.

“That’s been a pattern with U.Va. — they don’t like to admit that they’re responsive to student demonstrations of organization and power to determine decisions of the university level, but they often are,” Goldblatt said. “This tells us as faculty, as students, that we do have a lot of ability to determine what happens at the University of Virginia — you just have to get organized and make your case.”

Goldblatt further speculated that the administration's continued reluctance to execute the campaign’s demands stems from a fear that compliance threatens administrative legitimacy.

“Part of the reason that the University has refused to pay a living wage in response to student protest is that it acknowledges student power,” Goldblatt said. “That’s something they’re really deeply afraid of acknowledging.”

Questions of fairness

According to Murray, the University’s continued hesitation to heed the demands of the Living Wage Campaign centers primarily around issues of fairness. If the University were to index base wages to the cost of living — adjusting wages annually to comply with the Economic Policy Institute’s regionally-sourced-cost-of-living and inflation calculations — it would be a “slap in the face” to employees who have worked for years to receive higher wages if new employees were immediately given increased pay.

Murray further contends that two groups would be left entirely unaffected by a wage increase — those who have chosen to retain their retirement plan through the Virginia Retirement System and contracted employees. The former involves a complex legal arrangement through which 1,100 University employees elected a decade ago to retain their retirement plan with the Commonwealth of Virginia when the University began to offer retirement plans outside of the Commonwealth. These employees are referred to as classified employees, and only the Commonwealth can control their wages. The latter — employees contracted by the University through third-party companies like Aramark — likewise lie outside of the University’s pay scale.

The demand that contract workers be included in any wage increases has long been paramount to the Living Wage Campaign demands. Goldblatt said the issue of contracted employees is one largely “manufactured” by the University to delay action in raising wages.

“The University of Virginia often says that they cannot tell the contractors what to pay,”Goldblatt said. “That’s not true. Many universities do. Many universities who contract with Aramark say that one of their conditions is that the company has to pay their employees a living wage.”

One of those universities with a parity policy mandating the fair compensation of direct and contracted workers is Harvard University — President Jim Ryan’s previous place of employment.

Progress in a new Presidential administration

Ryan’s history at Harvard — along with his explicit support for an evaluation of worker compensation and recent formation of a working group to assess University-community relations — leaves both administration and activists with a guarded optimism for the future.

“[The issue of worker compensation] deserves thought and careful planning about whatever we do,” Murray said. “What we’re seeing is President Ryan and his administration doing that. I am highly hopeful that we will have progress.”

On Oct. 4 the Living Wage Campaign met with Jon Bowen, the Special Advisor to the President for External Affairs, to discuss President Ryan’s newly formed working group charged with assessing University-community relations. According to University Spokesperson Anthony de Bruyn, Ryan has committed to work with the Board of Visitors to address the living wage issue this academic year, although coming to any kind of resolution may take time.

The campaign said this a level of engagement they did not see in the administration of Teresa Sullivan.

“It’s a really big change from having Teresa Sullivan as president for the past couple years because she was completely unwilling to engage with Living Wage, with the hunger strikers,” Russell-Hunter said. “It’s been a really sharp turn in terms of Jim Ryan’s style because he’s very public facing in a way that Teresa Sullivan wasn’t.”

Fraiman said the enactment of a living wage would be the best pathway to ensuring Ryan’s inaugural mission — to rectify the discrepancies “between our aspirations and our realities” as well as to acknowledge controversies of the University’s past and present.

“In terms of the urgency of this right now, we’re all still traumatized and processing and trying to respond to the events of August 11 and 12,” Fraiman said. “I can think of no more concrete and ethical response to the events of August 2017 than for U.Va. to address the structural racism in our community by paying a living wage.”

Goldblatt expressed similar hopes for Ryan’s administration moving forward, adding that the community shouldn’t forget the role of activism in whatever decision it makes.

“We should remember that that victory is largely due to the work that workers, students, community members and faculty have been doing for decades at this point,” Goldblatt said. “This is a great opportunity for him — he can really start off his presidency on the right foot.”

This article has updated to accurately reflect the name and title of English Prof. Susan Fraiman.