Sam Bathrick’s documentary “16 Bars” opens with a shot of one of Richmond’s most famous and controversial monuments — a statue of Robert E. Lee on horseback, perched on a pedestal looming over Monument Avenue. Then the camera pans over top of the monument, moving into the city itself, and a rap song bursts to life in the background. It’s an angry track, and rightfully so, describing the experiences of underprivileged black people and their myriad struggles.

The film shifts to its first human subject — a black man talking about his early life in the city, his story mirroring much of the lyrics of the rap song. The man’s name Teddy appears onscreen, along with the words “Released from prison four days ago.” The audience doesn’t know it yet, but Teddy is also the frustrated, overwhelmed man shouting in the rap track.

“16 Bars,” one of the featured films of the Virginia Film Festival’s Race in America Series, follows four current and former inmates of Richmond City Justice Center — Anthony and Garland, both awaiting trial, De’Vonte, soon to be released and the recently-released Teddy. The four men vary in age, situation and even race — Garland is the only white inmate whose story receives in-depth depiction — but they are tied together by the common thread of the jail’s recording studio and Todd “Speech” Thomas, the man at its center.

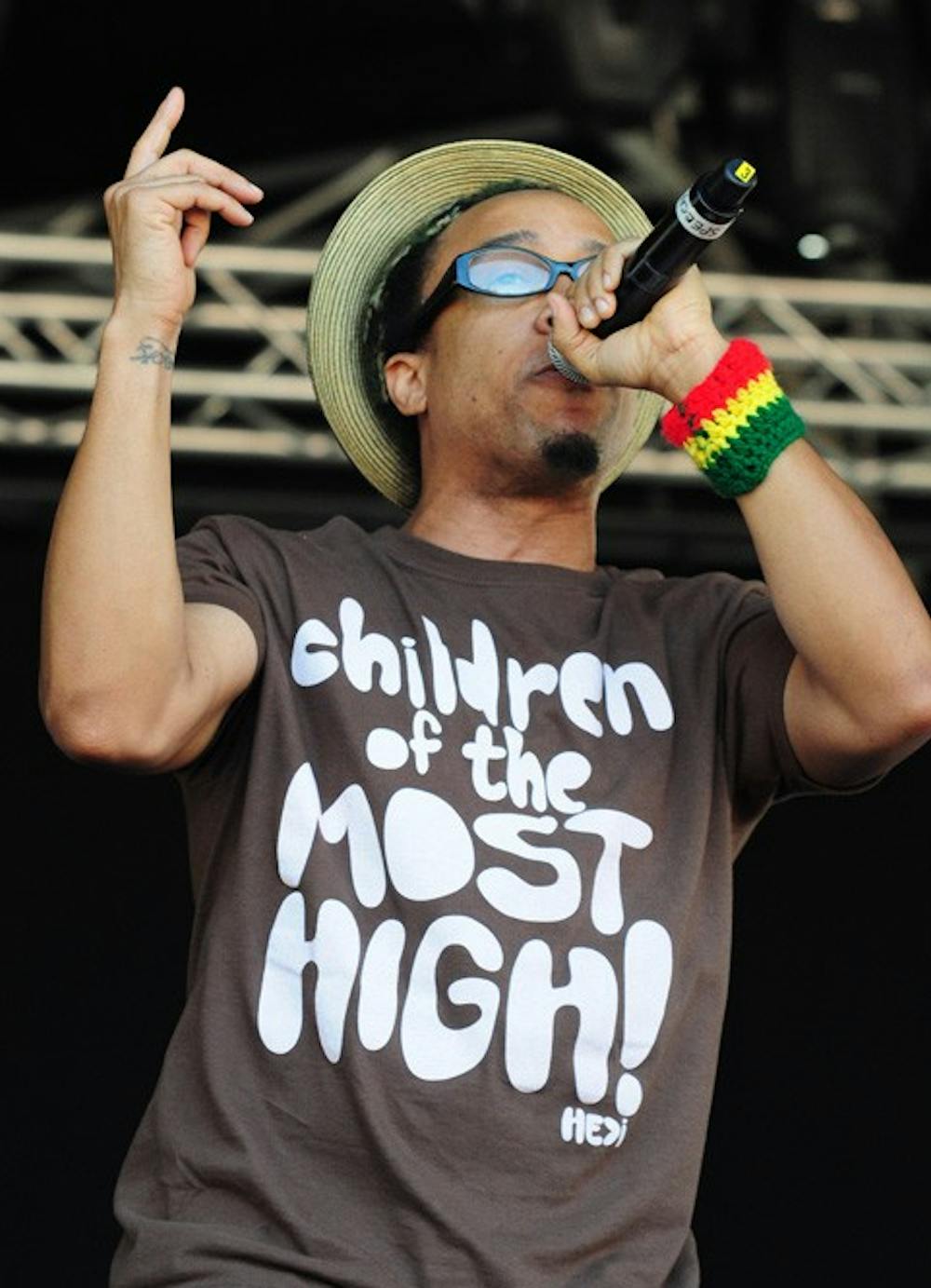

Thomas is the lead vocalist of Arrested Development, a hip-hop group which, aside from sharing a name with the cult sitcom, also shares the sitcom’s ability to create intricate, clever stories — the show through its episodes, the music group through their songs. “Mr. Wendal,” for instance, features Thomas describing the surprisingly deep conversations he has with the titular homeless man. “People Everyday,” in some ways a brilliant reworking of Sly and the Family Stone’s “Everyday People,” focuses on a date in the park gone violent when Thomas and his partner are threatened by a rude, aggressive group of men.

Thomas clearly has a penchant for stories and storytelling, and in “16 Bars” he brings that love to the Richmond City Justice Center. The film follows his role within the center’s recording studio as a sort of mentor, observer and friend of the four men in question, helping them find their musical voices while listening to the stories which the inmates have not yet been able to condense and express through song. These stories — the film’s most painful and complex, and often relating to the inmates’ initial reasons for incarceration — are told throughout “16 Bars,” through family members and loved ones, through employees of the jail and through the inmates themselves.

“Everyone is in some sort of transition,” Sarah Scarbrough says at one point in the documentary. She’s the program director of Recovering from Everyday Addictive Lifestyles — the REAL Program for short, and the means by which the recording studio exists — she’s referring to the fact that Richmond City Justice Center is only a short-term holding facility. Inmates either move from the jail to prison, or they’re released back into the city of Richmond. Through the four inmates depicted onscreen, both options are explored — but even if it’s the latter, seemingly positive outcome, it may only be a matter of time before the freed inmate returns to jail.

This concept — being caught in a cycle of getting arrested, jailed and released multiple times — is called recidivism, and it’s an idea that continually intrigues director Bathrick. In an interview with Arts and Entertainment, he said of “16 Bars,” “The goal of the film is ultimately to explore … the environmental, historical factors that lead people to jail and make it so hard for them to reenter [society].”

Thomas, as the film’s guide, is also concerned with the troubling concept of recidivism. As he interacts with the four inmates, he gradually acknowledges and comes to terms with his own privilege. Referring to one inmate whose life has been marred with parental abuse and the near-constant presence of drugs, Thomas says, “What would I have been if I came from that reality?” As the inmates try to rise above their own circumstances, often with heartbreaking results, a similar question will likely be plaguing viewers’ minds.

The documentary should be applauded for its focus on story rather than celebrity. Thomas is a Grammy-winning artist with valuable wisdom, but his story has been told many times in many different forms. The inmates, current or former, of Richmond City Justice Center — Anthony, Garland, De’Vonte and Teddy — have valuable stories to tell, and both the events depicted within “16 Bars” and the existence of the documentary itself gives these men the agency to be heard.

Their stories are beautifully unique, with no one tale feeling redundant, a concept reflected in their respective musical styles. As one of the depicted victims of recidivism, Teddy’s raps are bitter, introspective. He has been in and out of the system for much of his life, and viewers get a sense of his helpless frustration in his fast-paced but circular style on the mic. Anthony’s raps are at least marginally more optimistic — he is younger than Teddy — and his comparatively shy musical demeanor matches the lyrics. The same is true of De’Vonte, who incorporates beautifully plucked guitar into his songs. Garland’s music, featuring an acoustic guitar and mournful, southern vocals, is the most strikingly different of the four, but the same themes — frustration, regret, the consequences of one seemingly insignificant mistake — are present in his tunes.

This is not a story of happy endings, or endings at all — in the words of Bathrick, “16 Bars” is not a “single, broad brushstroke.” When each inmate is introduced, viewers are subjected to a slideshow of headshots, most of them mugshots. Hairstyles and expressions change, tattoos accumulate on some, but more than anything, one is intensely conscious of time passing. Some of the inmates are released during the course of the film — Teddy is already freed at the start — but freed does not mean free, and there is no guarantee for either success or happiness for any of the men in question. “There’s not a simple answer to that question of recidivism,” Bathrick said, calling it a “messy truth” that his film attempts to reach without necessarily coming to a definitive conclusion.

At one point late in the documentary, Teddy has a job interview that doesn’t go well. His despondency and hopelessness about his own future is painfully clear in this moment, especially when he says, “The world is moving so fast, and I’m so far behind.”

“16 Bars” is not a story proclaiming the injustice of incarceration, nor does it depict any of the inmates in an unrealistically positive light. It simply strives to tell the stories of those who are largely without voice. In a world where “moving so fast” often feels like the only option, “16 Bars” presents a convincing case for slowing down and attempting to understand lives foreign to most viewers — to give these men the time and respect they deserve.

“16 Bars” is showing at the Violet Crown Theatre on Saturday, Nov. 3 at 11:30 a.m.