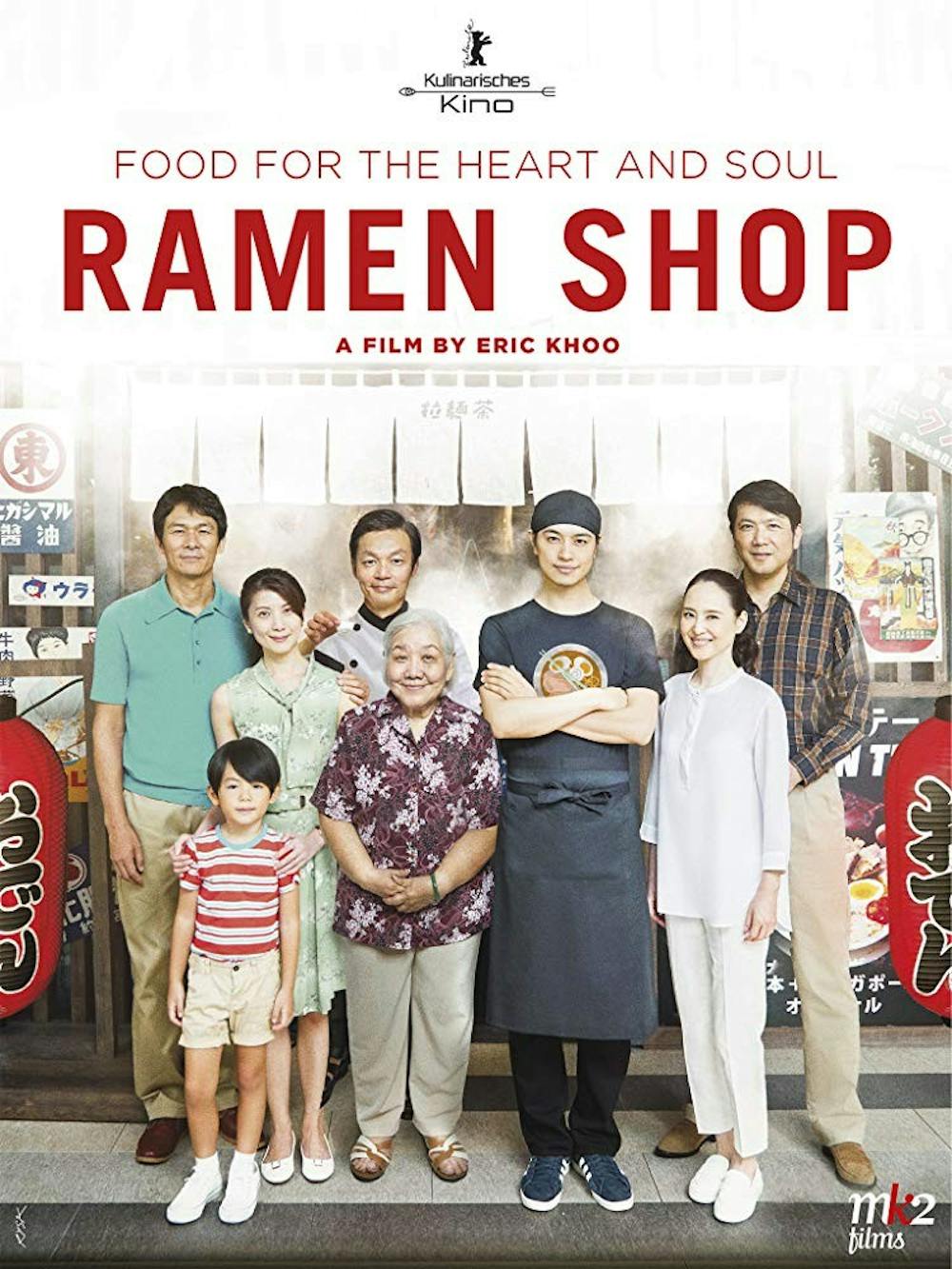

“Ramen Shop,” originally released under the title “Ramen Teh,” is a Japanese-Singaporean-French film submitted to the Virginia Film Festival for consideration for Best Narrative Feature. As far as narratives go, the film is rather cliché and simple but will at least be enjoyable for anyone looking for a quick bite of Singaporean culture.

The plot revolves around a young ramen chef named Masato (Takumi Saitoh) working out of his father Kazuo’s (Tsuyoshi Ihara) restaurant in Takasaki, Japan. Shortly after his father suddenly passes away, the orphaned Masato journeys to his city of birth in Singapore to reconnect with his maternal family, rediscover the culinary traditions of his adolescence and resolve the last regrets of his deceased mother Mei Lian (Jeanette Aw).

The key to all three goals, as it turns out, is cooking. Masato already knows how to cook, though, which limits the dramatic potential of “Ramen Shop.” The stakes are low throughout the movie, and the majority of the characters are largely unimportant. The film has a tendency to charge forward without bothering to firmly establish characters and locations. Many scenes start or end very suddenly, and the film seems to rely upon the audience to fill in gaps themselves based on small details and occasional flashbacks.

The film only seriously slows down whenever cooking is involved, as characters will take great pains to lengthily explain the cultural heritage and unique properties of the local cuisine. The film’s sound design intentionally emphasizes small, quieter sounds, always picking up the sound of clinking tableware, slurping soup or chopping vegetables. “Ramen Shop” seems to understand that the best way to simulate taste is by engaging the audience’s other senses. It’s a heavily immersive film, much less concerned with plot and characters than with mood and feelings. It certainly manages to make the food and the characters’ love of food feel real.

But making food look good is hardly a matter of cinematic mastery, and the film spends so long with so much cooking that it becomes difficult to shake the impression that it’s little more than a travelogue spliced with some mild family drama.

The real issue with “Ramen Shop” is depth. Masato’s journey to reconnect with his family is enjoyable and endearing, but it’s also overwhelmingly straightforward. The complexities of Masato’s home life and the difficulties of crossing cultural and linguistic barriers are wiped away in favor of a blanket treatment of peaceful family bonding. The film never stretches itself — content with its basic family dynamics and predictable. Although the film puts so much work into immersing the audience, “Ramen Shop” never engages viewers with any emotional range beyond simple happiness and sadness.

The film tries to flavor itself with Japanese-Singaporean culture clash, but doesn’t have much to say about how the cultures interact or their histories together. The soundtrack is especially odd in this respect, neglecting the opportunity for foreign instrumentation in favor of extremely generic, increasingly repetitive slow piano chords, undermining the sense of immersion that the rest of the sound design contributes.

“Ramen Shop” is a fine film for anyone looking for basic affirmation of simple family values. It has a simple story with likable characters and an earnest love of Singaporean cuisine. Though it may not be able to make audiences cry, it will at least make their stomachs growl.