The Honor Committee’s recently-released Bicentennial Report includes an in-depth review and analysis of the Committee’s Informed Retraction (IR) since its implementation in 2013. The report finds that the sanction option has reduced the number of hearings necessary in the adjudication process while also decreasing the number of guilty hearing outcomes.

The IR allows a student who has been reported to the Honor Committee for an alleged act of lying, cheating or stealing to take responsibility both by admitting such offense to all affected parties and by taking a full two-semester Honor Leave of Absence from the University community. A student may only file an IR during the seven-day period after the individual has been notified following the initial witness interview and before any hearing or trial process has begun.

Sanctions are those outcomes of cases in which a student is ultimately considered guilty — whether through an informed or conscientious retraction, leaving the University admitting guilt or through a guilty verdict handed down through an Honor trial.

The Bicentennial Report was released to the public Feb. 11 and is a comprehensive historical and statistical review of the Honor System at the University compiled and analyzed by the Committee’s Assessment and Data Management Working Group.

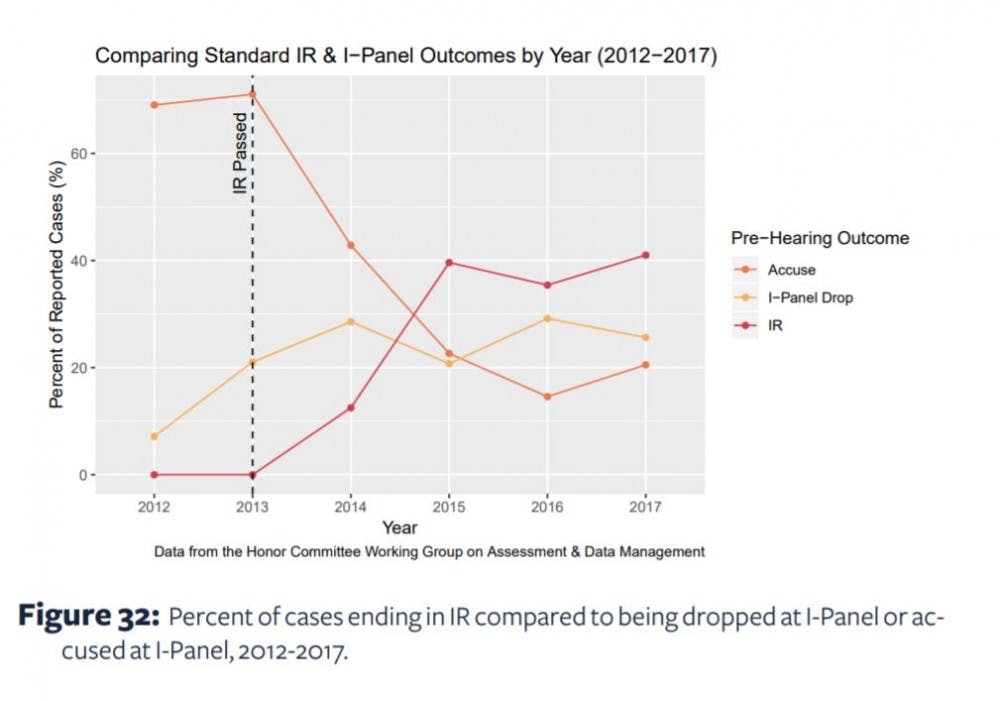

After the IR was incorporated into Honor’s Constitution in 2013 via University-wide referendum approved with 64 percent of the vote, the Committee’s sanctioning process was immediately altered, according to the report. Between 2012 and 2017, the IR comprised the majority of all sanctioned outcomes and more than 22 percent of all cases.

In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Ory Streeter, Honor Committee Chair and fourth-year medical student, said the implementation of the IR was quickly followed by a significant increase in the sanction rate for reported cases due to publicity generated by the Committee regarding the new sanction option. Streeter added that the implementation of the IR is one of the most dramatic overhauls in Honor’s history of adjudication since the Committee was established in 1912.

“I think a part of that probably is the fact that people were very, very aware of the Informed Retraction,” Streeter said. “They saw that it had come into place they knew that reports wouldn't necessarily end in an expulsion for a student who is willing to take ownership of the mistakes.”

For the past three years, according to the report, around 40 percent of reported students have chosen to file an IR. Despite criticism at the time of its approval, the implementation of the IR did not eliminate Honor’s long standing single-sanction policy at hearings in which a student found guilty during trial is immediately dismissed from the University.

However, during a University-wide referendum in the spring of 2016, the student body nearly voted to amend Honor’s constitution to allow for a multi-sanction system in favor of the current single sanction policy, but the measure failed to receive the required 60 percent majority of the total vote share. Honor’s current adjudication process is not considered to be multi-sanction as a guilty verdict after a trial has begun can only result in a student’s dismissal from the University. The 2016 referendum would have allowed for alternative sanctioning outcomes even after a hearing had begun.

In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Charlotte McClintock, a third-year College student who oversaw much of the report’s development as chair of the Assessment and Data Management Working Group, said concerns viewing the IR as a “plea bargain” are unfounded.

“So what's interesting is a lot of students worried that when the Informed Retraction passed that students who are not guilty would take an Informed Retraction as a plea bargain,” McClintock said. “We actually see that the proportion of students who [face] some type of sanction … relative to students who face no sanction … has actually stayed relatively constant over that period.”

Currently, students may only file a single IR during their time at the University. However, reforms to the process in the spring of 2018 enabled students to admit guilt to several Honor code violations under a single IR claim with the same outcome of readmission into the Community of Trust.

The IR is only one of several processes by which Honor adjudicates cases. For example, if a student commits an Honor violation and wishes to admit guilt to the offense before being reported, the individual may file a Conscientious Retraction in which he or she must make amends with the affected party and is absolved of guilt. The Conscientious Retraction was first approved by referendum which was codified into Honor’s constitution 1982.

Once an Honor violation is reported to the Committee, the accused student then has the opportunity to file an Informed Retraction. Otherwise, the case is brought before an Investigations Panel in which a panel of three Committee members review evidence to decide if there is sufficient cause for the case to proceed to a full trial, where final decisions on the guilty or not guilty verdict of the case are administered. Students may also avoid trial at almost any point by choosing to Leave Admitting Guilt after which students are unable to return to the University.

Between 2012 and 2017, guilty verdicts made up 15.2 percent of all cases, while Leave Admitting Guilt comprised 5.4 percent. Among outcomes where there was no sanction, I-Panel drops made up 22.5 percent of cases, 18.1 percent were not guilty and about seven percent were classified under the Contributory Mental Disorder policy; in which students undergo a psychological evaluation independent of Honor to assess how a mental illness may have contributed to an Honor offense.

In the past five years since its implementation, the IR has “changed the [Honor] system significantly in a number of ways,” according to the report. Fewer students have been accused at I-Panels as the proportion of students taking the IR has increased, meaning more cases are dropped at I-Panel. In 2012, before the IR went into effect, only about five percent of cases were dropped at an I-Panel. However, that rate had grown to more than 25 percent by 2017.

“Students with enough evidence in their case to pass the ‘more likely than not standard’ at I-Panel and be sent to hearing are choosing to make IRs instead,” according to the report. “After the introduction of the IR, LAG outcomes and guilty verdicts at hearings decreased and students choosing to make the IR increased by around the same amount, suggesting that students who would have previously been found guilty at a hearing or left admitting guilt are now choosing the IR.”

Streeter said the implementation of the IR has encouraged students, who have ample evidence presented against them regarding an Honor violation, to take responsibility for their actions early in the process rather than facing a lengthy adjudication process with a likely guilty outcome.

McClintock added that students who are claiming IR sanctions likely would have been found guilty during a trial.

“Students who have taken the Informed Retraction in the most recent years are often the same students who would have been found guilty at a hearing in previous years,” McClintock said. “Where the proportion of students who have been found not guilty — either by drop by the executive committee, drop by the investigative panel or who are found not guilty to hearing — has stayed relatively the same over the course of the six year period.”

Consequently, while the number of hearings per year has rapidly declined overall — from 25-30 cases annually before the IR to less than 10 in 2016-2017 — the number of guilty verdicts has increased, while not guilty has decreased. Between 2012 and 2017, not guilty case outcomes peaked at nearly 40 percent before declining to only 10 percent of all case outcomes by 2017.

By comparison, guilty verdicts made up nearly 38 percent of all case outcomes in 2012 followed by a sharp decline in subsequent years with only 12.5 percent of cases ending with guilty verdicts after trial in 2017.

As a result, Streeter said the implementation of the IR has not only transformed how students are adjudicated for Honor violations but the internal operation of the Committee itself.

“Hearings are a monumental endeavor,” Streeter said. “They require tremendous work by dozens of people [and] hours and hours and hours of preparation to make sure that we do that job well. And so when you go from having 35 a year down to less than 10 ... [it is] without a doubt, less work for the Committee.”

Streeter also said the significant decrease in internal case processing and other operations related to the conduct of Honor trials has allowed the Committee to reflect on its adjudication process and its outcomes through efforts such as the Bicentennial Report. He added that such a data driven review likely would not have been possible for the Committee to carry out before the implementation of the IR.

A complete copy of the report and additional information regarding Honor’s history, evolution and development is linked here.