The Honor Committee’s recently-released Bicentennial Report includes extensive demographic data analysis of the body’s reporting rate for students at the University since 2012 — including statistics which reveal a disproportionately high reporting rate of Asian American and international students.

The Bicentennial Report was released to the public Feb. 11 and is a comprehensive historical and statistical review of the Honor System at the University compiled and analyzed by the Committee’s Assessment and Data Management Working Group.

The report is the largest internal review of Honor at the University, featuring data from a century of annual dismissals, three decades of data on all sanctions and six years of full data from reports and outcomes. Sanctions are those outcomes of cases in which a student is ultimately considered guilty — whether through an Informed or Conscientious Retraction, leaving the University admitting guilt or through a guilty verdict handed down through an Honor trial.

According to the Honor Committee’s website, a Conscientious Retraction allows a student who has committed a dishonest act to admit his or her actions and accept the respective consequences without leaving the Community of Trust. This admission, however, must occur before the student gains any knowledge that someone might suspect them of an Honor Offense.

The Informed Retraction allows a student who has been reported to the Honor Committee for an alleged act of lying, cheating or stealing to take responsibility both by admitting such offense to all affected parties and by taking a full two-semester Honor Leave of Absence from the University community. A student may only file an Informed Retraction during the seven-day period after the individual has been notified following the initial witness interview and before any hearing or trial process has begun.

The African American student population at the University has gradually declined from nine percent in 1991 (1,698 students) to six percent in 2018 (1,542 students). However, the Asian American student population has doubled from six percent of University students in 1991 (1,109 students) to 12 percent in 2018 (2,877 students). Meanwhile, the white student population has gradually declined from just over 75 percent in 1991 (13,402 students) to about 65 percent in 2018 (14,168 students) of the total student body.

Between 2012 and 2017, the Honor Committee received an average of 40 to 60 reports each year. According to the report, a 2012 survey conducted by the Committee revealed that 4.7 percent of students admitted to committing an Honor offense during their time of enrollment at the University.

Once an Honor violation is reported to the Committee, the accused student then has the opportunity to file an Informed Retraction. Otherwise, the case is brought before an Investigations Panel in which a panel of three Committee members review evidence to decide if there is sufficient cause for the case to proceed to a full trial, where final decisions on the guilty or not guilty verdict of the case are administered.

Despite some improvements in recent years with regards to disproportional sanctioning for certain demographic groups, reporting rates of Asian American and international students in particular have remained well above the group’s student population at the University.

In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Charlotte McClintock, a third-year College student who oversaw much of the report’s development as Chair of the Assessment and Data Management Working Group, said analysis of disproportionately high reporting rates did not reveal significant effects on facing sanction for race, gender or student athlete status. However, she added that higher reporting rates did correlate to increased sanction outcomes for international status, reporter type and student year.

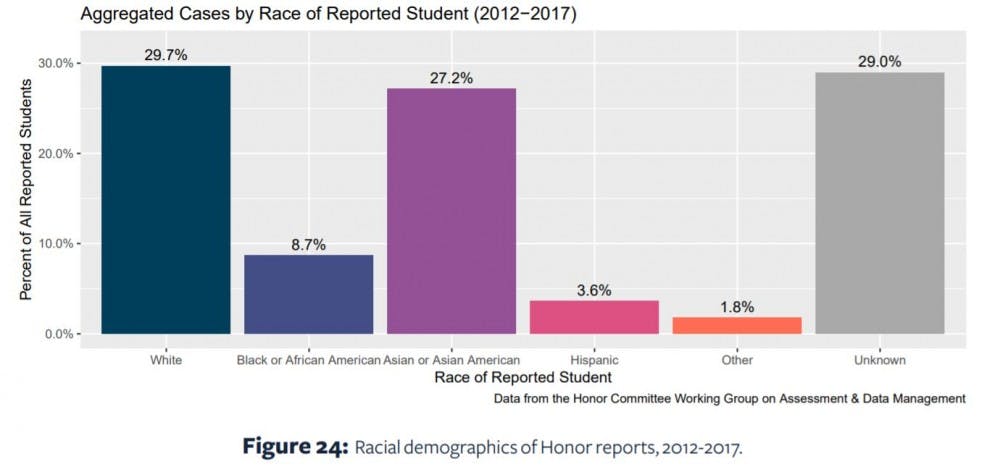

Between 2012 and 2017, Asian American students comprised 27.2 percent of all reports, while African American students made up 8.7 percent. By comparison, about 30 percent of reports were white students. However, the report notes that reporting data varies from year to year and is highly incomplete as many cases during the time period have no race attached to them due to incomplete information in the Student Information System and changes in the internal case management system.

Nearly 30 percent of all cases from 2012 and 2017 have no race associated with them. In 2012, more than 60 percent of cases had no racial identification associated with them. As a result, the presented proportions are the minimum possible value for each group.

However, the report notes that 62 percent of cases involving international students lacked any racial identification but adds that almost all of the remaining cases involved Asian American students. Despite only making up 10 percent of enrolled students at the University, international students had a nearly 30 percent report rate.

International students are far more likely to receive sanctions than domestic students after being reported. More specifically, 32 percent of reported international students claimed an Informed Retraction, while 19 percent of domestic students did so. Of the reported international students, 19 percent were found guilty through a trial as compared to 14 percent of domestic students.

According to an analysis in the report by Derrick Wang, a third-year College student and Honor’s Vice Chair for Community Relations, the top three countries of citizenship for international students at the University in fall 2017 were China, India and the Republic of Korea, respectively. During this time, graduate international students from China and India made up 41 percent of all international students, while Chinese international students comprised nearly five percent of the total student body.

While Wang writes that it is difficult to pinpoint the exact cause of the disproportionally high reporting and sanctioning rate for international students, he attributes the trend to a number of possible forces. More specifically, he said this could be due to a lack of knowledge on the University’s Honor code due to linguistic, academic or cultural differences, academic and financial pressures stemming from high cultural expectations and an being in an unfamiliar environment as well as implicit bias in faculty.

“It is possible that some faculty members could have implicit biases that lead them to scrutinize international students more, leading to more reporting of international students,” Wang writes. “While it is unlikely that professors and faculty are explicitly targeting international students, they may implicitly suspect international students of cheating more often. This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy, since greater suspicion could lead professors to scrutinize international students work more closely, which could confirm the original bias.”

White students make up 29.7 percent of reported students but made up 58 percent of the student population in 2017. However, Asian students are significantly over-represented among students reported to Honor relative to their representation at the University as they constitute at least 27.1 percent of reported students but are only 12 percent of the University’s domestic student population.

African American students are over-represented at 8.7 percent of reported students while making up only six percent of the student body. However, the proportion of African American students relative to all reported cases has declined significantly over the past 30 years. Hispanic students are underrepresented, making up six percent of students but 3.6 percent of reported students.

However, despite the disproportionate reporting rates for Asian and African American students, the report states that those who were reported proved to be sanctioned at a proportional rate to other groups.

“We did not find any evidence that minority students were less likely to face sanction than non-minority students, which suggests that minority students are not being falsely reported to Honor,” according to the report.

The racial disparities found in reports of Honor offenses may be rooted in the variability of reporting rates across the several schools at the University and their respective demographic breakdown, according to the report.

In terms of gender discrepancies in reporting between 2012 and 2017, female students make up 39.4 percent of students and male students comprise 55.1 percent, with 5.4 percent unknown. The University has a student population that is 54.9 percent female and 45.1 percent male, meaning male students are overrepresented by 10 percentage points relative to their population.

Data from 2012 to 2017 also show that student athletes at the University are more likely to be reported for an Honor offense but ultimately receive sanctions at the same proportion as other students. Student athletes made up 7.6 percent of reports, 43 percent of whom were sanctioned as compared to the 44 percent sanction rate for non-athlete students.

There are currently 854 student athletes at the University — 3.4 percent of the total student body. Given that only 21 student athletes were reported between 2012 and 2013, the report notes that the data cannot be conclusively linked with other identifying factors.

College and Engineering students racked up the most reported Honor offenses, with the majority — 60.9 percent — of all reports coming from professors. College students comprised 54.4 percent of all reports during this time, while Engineering students made up 13.5 percent. What appears to have a major impact on the reporting rates, however, is the size of the schools themselves.

The Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, for example, had an almost two percent report rate within the school with only 5 reports over the 2012-2017 timespan. The College on the other hand had an almost 1.2 percent report rate but had 149 cases over the same time.

Anybody can report someone to the Honor Committee for an Honor offense, but professors bear the brunt of the reported cases in the 2012-2017 frame, making up 60 percent of all reported cases. Students reported 17.9 percent of cases, higher than the 12 percent reported by teaching assistants.

Higher-year students were also more likely to be reported, with third-years the most likely to be reported for an Honor offense, racking up 36 percent of cases. Second- and fourth-years were close behind, taking 19.3 percent and 17.1 percent of cases respectively.

“It may be true that third-year students were more likely to be in smaller classes where they were more likely to be caught cheating than first-year students in a large lecture hall,” the report reads. “Or it could be that third-year classes may be more challenging or may be required for the student’s major, thus giving higher necessity and incentive to cheating behavior.”

McClintock said this trend could be the result of class size for higher-year students.

“A first-year student might be reported for cheating in a large lecture hall potentially by another student or by a faculty member who maybe saw them,” McClintock said. “Whereas a student who's in a 15 person seminar might have a close relationship with a professor and might be more likely to be caught cheating with stronger evidence.”

In cases involving Graduate students, 61 percent of defendants were sanctioned — the highest out of any year — but still made up only about 11 percent of reported students overall. First-years were the least likely to be sanctioned, with only 25 percent of cases ending in sanctions.

A complete copy of the report and additional information regarding Honor’s history, evolution and development is linked here.