Recently, the Kipnis Lab led groundbreaking research that linked waste removal in the brain to Alzheimer’s Disease. Jonathan Kipnis, the director of the University’s Center for Brain Immunology and Glia and chair of the department of neuroscience, and his team of researchers discovered that insufficient waste drainage by the meningeal lymphatic vessels of the central nervous system was associated with impairments in learning and memory.

The scientific community used to have different ideas about how waste — such as cellular debris and large molecules — was removed from the brain. Initially, researchers thought that this waste was removed through the blood-brain barrier, a system that can mediate excretion from the brain into the blood.

However, in 2015, the Nedergaard Lab in the University of Rochester discovered a new waste removal mechanism — the glymphatic system.

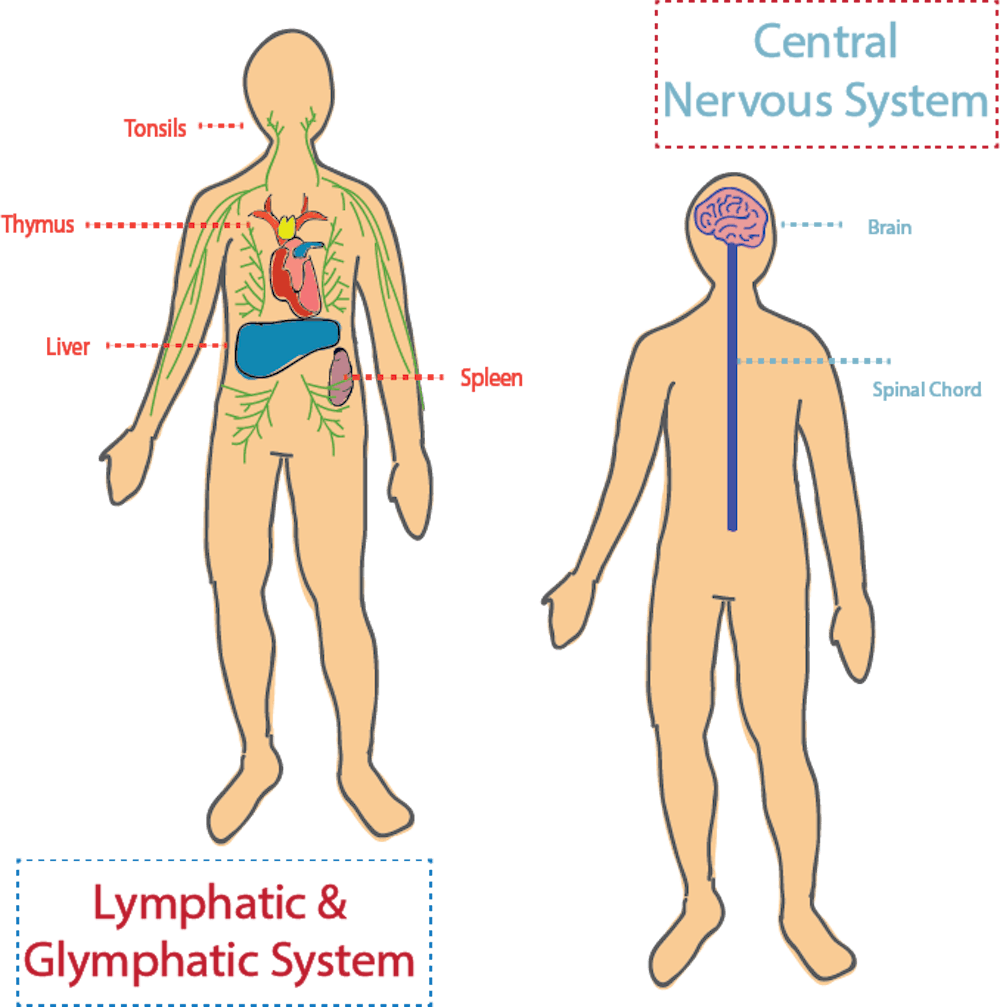

The glymphatic system is a waste removal pathway with spaces along the brain’s blood vessels that allow the exchange and drainage of brain components — such as cerebrospinal fluid, or the liquid around the brain and spinal cord — along the brain membranes.

After this discovery, researchers in the Kipnis Lab wondered how the glymphatic system affected other systems in the brain.

“And of course, now that we have another component, another system that is able to remove waste from the brain, now what's interesting is trying to figure out how all of these systems communicate with each other and if one becomes impaired, how that impacts on the function of the other systems,” said Sandro Da Mesquita, a postdoctoral researcher in the Kipnis Lab involved with this study.

Having studied the role of the lymphatic vessels in the brain, the team was interested in investigating a potential connection between the glymphatic system and these vessels, which transport organic molecules and drain cerebrospinal fluid in the brain.

“What we were wondering, is if this system that drains CSF [cerebrospinal fluid] is somehow connected and is able to influence this recirculation through the glymphatic system,” Da Mesquita said.

Through experimentation, Da Mesquita and his fellow researchers discovered the relationship between the lymphatic vessel function and behavioral capabilities in mice.

“If you dampen the function of these vessels in adult mice, that leads to behavioral impairments,” Da Mesquita said. “Seeing that this was the case, we wanted to see if, with aging, these lymphatics would become impaired.”

After seeing that lowered vessel function is associated with behavioral impairments in mice, researchers in the lab began to investigate whether aging — which relates to behavioral abnormalities — also affects vessel function. The team observed that aging impeded the ability of lymphatic vessels to function properly.

The lab also discovered that a decrease in the lymphatic function caused an increase in the accumulation of amyloid beta — a sticky protein that accumulates in the brain and disrupts communication between brain cells. This protein is the main component of plaques that disrupt neuron function in Alzheimer's Disease, implying that poor lymphatic vessel function is potentially involved with it.

The next step, Da Mesquita said, was to think about potential ways to rescue the lowered function of vessels. The Kipnis Lab used a specific protein that acts as a growth factor for lymphatic vessels, and that improved the function of the lymphatics.

“Through this approach, what we saw is that we were able to increase the diameter of the lymphatic vessels,” Da Mesquita said. “These vessels in old mice, they started to drain more macromolecules from the cerebrospinal fluid.”

Enhancing lymphatic vessel function not only boosted the mice’s cognitive capabilities, including learning and memory but also helped glymphatic recirculation, supporting the idea that the two systems are connected to each other.

According to Da Mesquita, immune therapies for Alzheimer’s Disease might be more effective if waste and crucial brain components can be effectively drained and recirculated via the lymphatic vessels.

So far, Kipnis Lab’s research has been published in the National Institute of Health’s list of most promising advances in 2018 and the prestigious scientific journal Nature.

Josh Barney, senior marketing and public relations specialist at the University’s School of Medicine, pointed out the study’s relevance as envisioned by the National Institute of Health in an email to The Cavalier Daily.

“The NIH is a wonderful supporter of basic science — fundamental science that advances our knowledge of human health and serves as the foundation for future treatments and cures,” Barney said. “The recognition of the discovery by Dr. Kipnis and his team speaks to the finding’s great potential importance to our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and the effects of aging on our cognitive abilities.”

While current therapies for Alzheimer’s disease focus on bringing disruptive proteins to healthy levels, this study instead highlights the importance of lymphatic vessels in paving a new path for therapies.

Kipnis said in an email statement that the lab is also trying to examine how meningeal lymphatic cells are distinguished in various neurodegenerative diseases.

“The goal is to target meningeal lymphatics as a therapeutic target for brain diseases,” Kipnis said in an email.

He further said that the lab is working to better understand the lymphatic vessels in order to potentially use them as the target of new therapies.

Correction: This article previously misstated that the Kipnis Lab discovered the connection between the glymphatic system and neurodegenerative diseases, when it actually discovered the connection between the meningeal lymphatic system and neurodegenerative diseases. Additionally, the article referred to Ph.D. Researcher Sandro Da Mesquita as Mesquita instead of Da Mesquita. This article has been updated to reflect both of these changes.