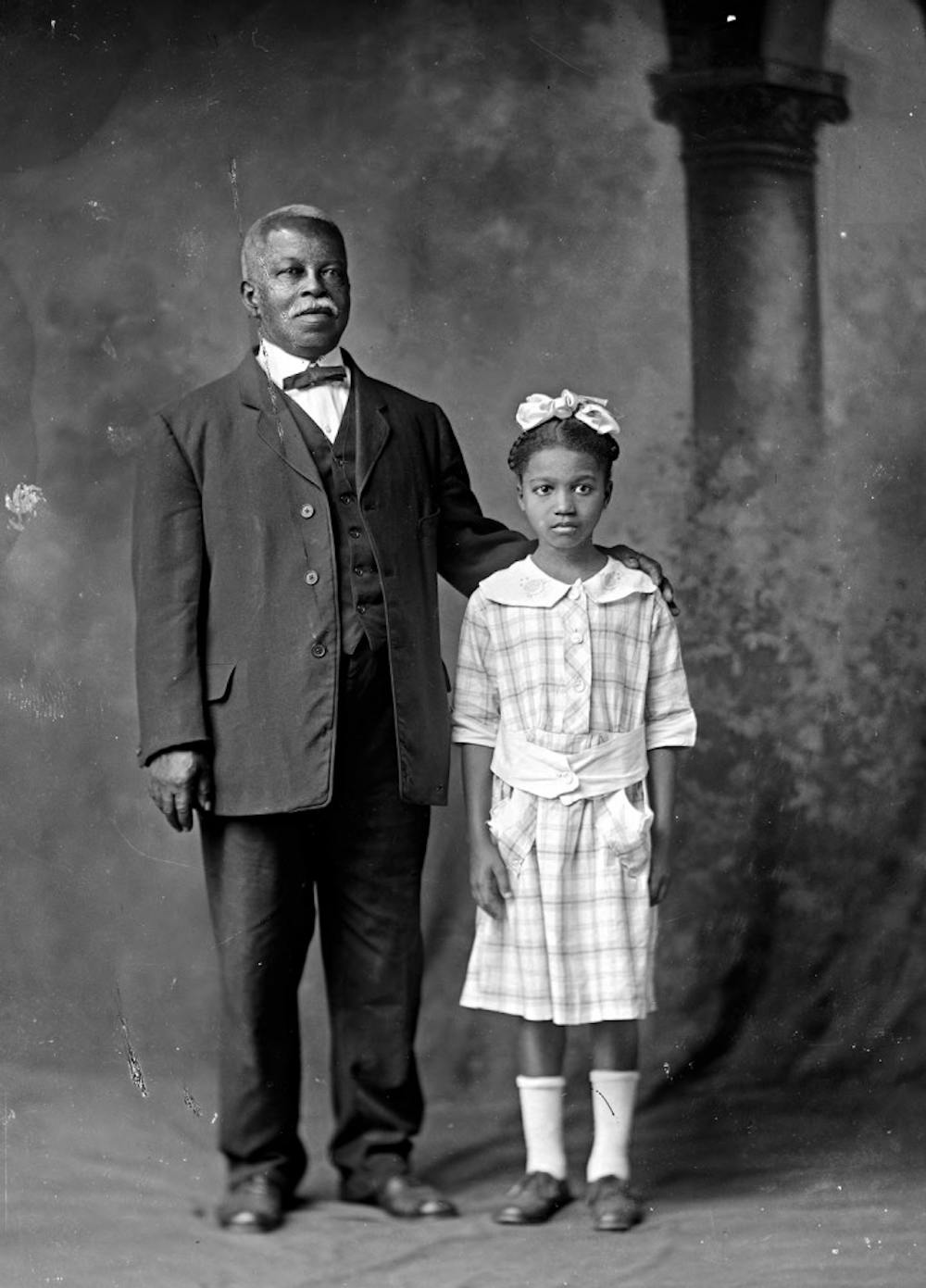

Personal family photographs can serve as a powerful counter-narrative to established visual media, like Confederate monuments, that share a limited and often misconstrued version of history. The dignity of the individuals in these pictures hints at the resilience and boldness of black Americans in Charlottesville in spite of the extremely unequal and reinforced conditions of the Jim Crow era.

Assoc. Professor John Edwin Mason, who specializes in African history and photography, has worked with Charlottesville’s Blue Ribbon commision to establish the Holsinger Photo Project, a series of events and exhibitions intended to display studio photographer Rufus Holsinger’s portraits of black families and individuals from the early 20th century, a time of explicit racial segregation. Mason will begin the project on Saturday, March 9 with its first public event, Family Photo Day, at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center.

The event will display the portraits while hoping to gather descendants of the pictures’ subjects to reveal new stories about their family history and experience in a segregated and bitterly divided America. Free portraits will be done for families attending the event, celebrating the spirit of photography as an accessible and visually potent medium for preserving both personal and cultural histories.

Below is an interview conducted by Arts and Entertainment with Mason before the event, in which he described his aspirations for the Holsinger Photo Project as a whole, as well as the place of photography in telling larger American narratives of repressed racial histories.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Arts and Entertainment: So first of all this event on Saturday, it’s exposing hidden histories in Charlottesville … specifically through photography. What are the general stories that you're expecting to be told and what value do you think they're going to have?

John Mason: So my interest in this started when I served on the City's Blue Ribbon commission, which made recommendations to City Council about our Confederate monuments, and in the course of our work, I became really impressed with the way that those Confederate monuments tell their story without words ... to look at those Confederate monuments is to know that the men on the horses are admirable, that the cause for which they fought was glorious. And it's a history that both valorizes the Confederate South but also erases the history of slavery and racial oppression.

And without words these statues speak and tell [a] kind of history. It's a history that I find is a false history, but they tell a story nonetheless.... The story of the black community has largely not been told. And there are people who are doing this through conventional text based writing of history. But in the halls of [this] photo project we thought we could do this by using the same technique as the monuments as that is to tell a story visually.… The portraits show you self-confidence, they show you strength, they show your resilience, they show family, they show community, they show romantic love, they show beauty. You know, all of these things that American visual culture was denying to African-Americans at the time.… We're doing public history with what had been private archives. And that is, I think, really going to transform the way that this city and the region sees its history.

AE: With so much focus on Charlottesville's own complicated racial history, you know, following Aug. 11 and 12, do you think that that's actually boosted the signal of these people's stories or that that's actually contributing to more noise to it?

JM: I think the interest in uncovering the untold stories of Charlottesville's history started with the Blue Ribbon commission. It started with the work that we did in changing the way that Charlottesville saw its past. But it's absolutely been accelerated after August the 12th. There was a lot of introspection.… There are filmmakers out there collecting oral histories and making films, short films, documentaries about Charlottesville's history.… There's a lot of energy and the Holsinger portrait project is part of that.

AE: But … being inundated with multimedia flashy things — these like, black and white photo prints — what is the capacity and potency of storytelling they still have today?

JM: I think these prints ask people to slow down and pay attention.… So, let me just give you a quick for instance — we have already a descendant of the two black barbers who ran a barber shop where The White Spot is now on the Corner. The descendant of those two black barbers who were brothers, has come forward and says, “My ancestors are in that Holsinger photo!” And sure enough Holsinger made a photo on the Corner of the people who were the proprietors of the shops on the Corner. And most of them, as you would expect, are white proprietors, but it was common in those days for black barbers to have white clientele. And sure enough these two brothers who were both barbers are standing in front of their barber shop and their barber shop is where The White Spot is now. So you know we're connecting … a local physical location to a living descendant to the men in white coats standing in front of this spot. And so it's really remarkable.

AE: The families getting these photos at the time would have to mean they would have to be of some means or business owners, right?

JM: Well, no. We [were] really surprised about that. It was not cheap to get a photo made by Rufus Holsinger, but it was also not so expensive that ordinary working people couldn't save up and go in. You're only having it done probably once during your lifetime, right? So it's very clear from the clothes that people are wearing that you know, they're not necessarily middle class. So we've got a number of people who in these portraits who are working people, you can tell by their clothes, you can tell by the condition of their shoes.… Charlottesville did have a tiny, tiny black elite, you know doctors, teachers. They show up, but so do common laborers and housekeepers. And that's really one of the things we like a lot about this, it shows the big broad breadth of the African-American community.

AE: From what you're saying it sounds like you know photography was this … aspirational but approachable medium for a lot of people. I think most people would probably agree that's not the way it is today. So just ending and looking towards the future, is there something that's just out of reach that we value, a medium that is maybe new and developing that you think is going to preserve stories as we still face problems and racism in this country?

JM: I think about that a lot. And people were very self-conscious about how they wanted to look when they went to Holsinger's studio because photography was still expensive. You know, it was relatively expensive which meant it was relatively rare. Which meant that most people didn't have a lot of snapshots of them, right? You had that portrait and you can see how people are presenting themselves to the camera, that they've that they've at least given a lot of thought to how they're dressing and they're taking this as a very serious occasion. We don't do that anymore. And we've got this proliferation of images. I also don't know if they will be preserved, right?

So Holsinger left us 10,000 of his negatives there in this incredible resource — they're in the Special Collections Library. I know people have 10,000 pictures on their phone, right? There are individuals running around with 10,000 pictures on their phone. And who's going to store the billions upon billions of images that are circulating around? I don't know.… I wonder, you know, how are we going to have access to the personal feelings of people who are living in our generation? You know, if in some miraculous way you can find their Instagram feed you could learn a lot about them, but historians don't like to speculate about the future.