Six months before child molestation allegations ravaged his career, Michael Jackson sat in a theater at Neverland Ranch — his residence in Santa Barbara County, California — for an interview with Oprah Winfrey. The event, watched by an estimated 90 million people, was a fluffy promotional vehicle for the music video of “Give In to Me,” a song from Jackson’s eighth studio album, “Dangerous.”

“One of the things that really impressed me the most,” Winfrey said of the theater, “is that there are, built inside the walls here, beds — beds for some of those sick children who come.”

In “Leaving Neverland,” a new two-part documentary from director Dan Reed, one of these beds becomes a site of child sexual abuse by Jackson, making Winfrey’s conclusion to the exchange particularly startling — “you have to be a person who really cares about children to build it into your architecture.”

The interview was one of the last moments of popular innocence for Jackson — before a succession of sexual abuse allegations from multiple boys. By the time Jackson died in 2009, his reputation was in shambles, with personal crisis eclipsing artistic achievement.

Since his death, Jackson has occupied a peculiar cultural space, less controversial than celebrated, but with the memory of his alleged crimes still intact. Celebrities flocked to his public memorial service, a 2009 documentary edited to coherence a series of erratic concert rehearsals and his estate signed a reported $250 million deal with Sony to release new music. Then-real estate mogul Donald Trump epitomized the posthumous hagiography of Jackson, concluding in 2009 that Jackson was “not going to be remembered for the last 10 years” but instead “the first 35 years” — before any of Jackson’s accusers went public but after most allege Jackson began sexually abusing them. With the person gone, what remained was the persona.

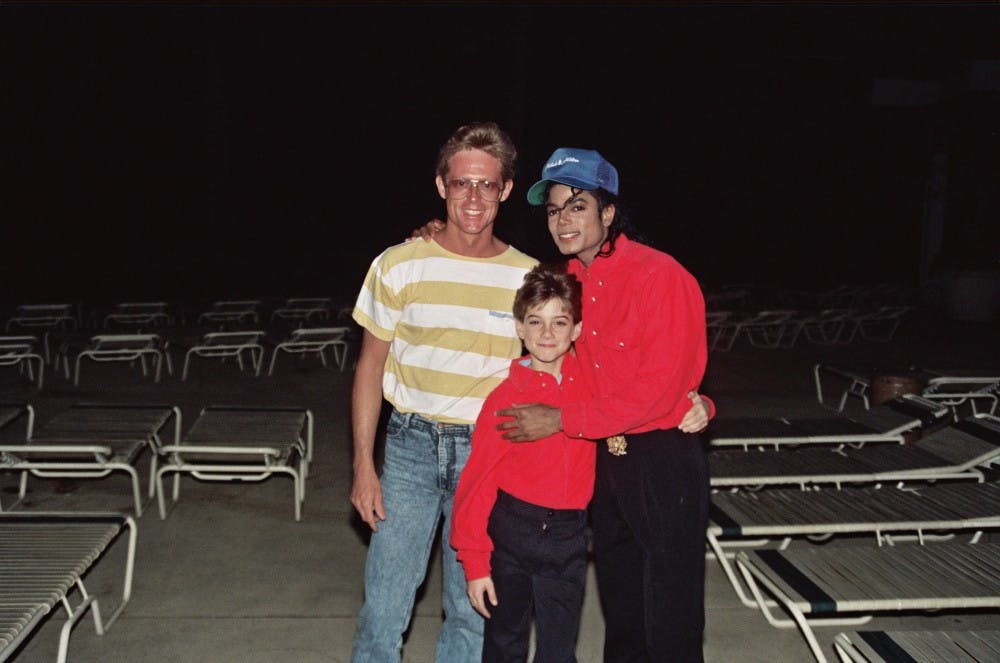

When two men came forward in the years following Jackson’s death with molestation allegations, they were treated with collective indifference. This followed earlier denials from the men that Jackson sexually abused them but also reflected a broader culture of complicity. One of the men, choreographer Wade Robson, aired his allegations in a 2013 interview with “Today” show co-host Matt Lauer, who faced his own allegations of sexual misconduct in 2017.

The other man, James Safechuck, accused Jackson of sexual assault in 2014, and “The Breakfast Club” presenter Charlamagne Tha God — who himself was charged with sexual assault in 2001 — awarded Safechuck “Donkey of the Day,” a disparaging title from a recurring segment on the show. Because Robson and Safechuck came forward prior to the #MeToo movement and the resurfaced allegations against Bill Cosby, their claims — along with those of prior Jackson accusers — are long overdue for public reevaluation.

In “Leaving Neverland,” Reed interviews both Robson and Safechuck. “After Neverland,” a pre-taped follow-up to the documentary, finds Winfrey interviewing Robson, Safechuck and Reed. There are now five people accusing Jackson of sexually abusing them — Jordan Chandler, Jason Francia, Gavin Arvizo, Robson and Safechuck. Unlike the two accusers who testified against Jackson at his 2005 trial, Robson and Safechuck are both white. For all the changes in American culture over the last 14 years, white perspectives are still privileged — a distinction left unacknowledged by Reed, who barely addresses Jackson’s other accusers and only briefly incorporates a Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office interview with Arvizo.

In contrast to earlier televised examinations of Jackson’s character, Reed’s does not prominently feature Jackson’s music, but instead a brooding score from composer Chad Hobson. Although Jackson’s music was never a licensing option for Reed, its relative absence aligns the documentary with cancel culture — “Thriller,” “Bad,” “The Way You Make Me Feel,” “Smooth Criminal,” “Billie Jean,” “Tabloid Junkie” and “Black or White” make brief appearances in the film, but only in archival footage, not as musical backing to molestation claims.

Reed has claimed “Leaving Neverland” is not “a film about Michael Jackson,” yet it is an impossible film without Michael Jackson. The predator depicted in “Leaving Neverland” provides a paradigmatic example of child grooming, but he also provides an anomalous one — most pedophiles don’t control the media narrative about their sex lives, and most child molesters cannot afford to buy an accuser a house.

For all of Jackson’s railing against the media — with songs like “Leave Me Alone,” “Tabloid Junkie” and “Privacy” — the conventions of journalism have long given him a useful bulwark against claims of sexual abuse. With high-powered attorneys and the fortune to silence accusers, Jackson benefitted for years from a system that tethers the language of guilt to criminal conviction.

Only Jackson and his accusers would have witnessed the abuse alleged in “Leaving Neverland,” but the gullible response to the allegations is to find a stand-in for Jackson — someone to answer the charges in his absence. “Leaving Neverland” conspicuously does not do this, but much of the media reaction to the film has, broadcasting statements from the Jackson family and estate alongside statements from accusers. Why these accounts matter in assessing his guilt is unclear — according to Reed, they are “people who were not harmed by an individual who has done harm,” and the Jacksons themselves admit to never watching the film, so their authority to discuss it is dubious.

“Leaving Neverland” should not be shocking. The fact that it is indicates a culture that never truly listened to past accusers. The film does not reconcile its version of Jackson with Jackson’s public persona. It is a document of alleged abuse, not a study of complicity. Still, when Safechuck says Jackson would give him jewelry for sexual favors, it recalls Francia’s claim that Jackson gave him cash for incidents of sexual assault. When Safechuck says Jackson introduced him to masturbation, it recalls Arvizo’s claim that Jackson told him “men have to masturbate.” Reed’s film is graphic, but aside from a description of anal sex, it is hardly more graphic than previous allegations against Jackson. What has changed since Jackson’s trial is a collective willingness to listen.

Much of the conversation around Jackson operates on the presumption that talent and sexual abuse are mutually exclusive — that Jackson is innocent because he was transcendent. This is a dichotomy Kendrick Lamar explores in “Mortal Man” — “that n—a gave us ‘Billie Jean,’ you say he touched those kids?” It is also a dichotomy acknowledged by Robson and Safechuck and promoted by the Jackson estate, which counterprogrammed “Leaving Neverland” with two of Jackson’s concert specials.

Evaluating Jackson by artistic achievement alone means ignoring credible stories of sexual abuse. To quote Jackson’s lyrics — “Every path you take you’re leaving your legacy.”